|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 16(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the difference in early disc height loss following transforaminal and lateral lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF and LLIF).

Overview of Literature

Minimal disc height loss facilitated by the polyaxial screw heads can occur naturally due to mechanical loading following lumbar fusion procedures. This loss does not usually cause any significant foraminal narrowing. However, when there is concomitant cage subsidence, symptomatic foraminal compromise could occur, especially when posterior decompression is not performed. It is not known whether the type of procedure, TLIF or LLIF, could influence this phenomenon.

Methods

Retrospectively, patients who underwent TLIF and LLIF for various degenerative conditions were shortlisted. Each of their fused levels with the cage in situ was analyzed independently, and the preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up disc height measurements were compared between the groups. In addition, the total disc height loss since surgery was calculated at final follow-up and was compared between the groups.

Results

Forty-six patients (age, 64.1±8.9 years) with 70 cage levels, 35 in each group, were selected. Age, sex, construct length, preoperative disc height, cage height, and immediate postoperative disc height were similar between the groups. By 3 months, disc height of the TLIF group was significantly less and continued to decrease over time, unlike in the LLIF group. By 1 year, the TLIF group demonstrated greater disc height loss (2.30±1.3 mm) than the LLIF group (0.89±1.1 mm). However, none of the patients in either group had any symptomatic complications throughout follow-up.

Conclusions

Although our study highlights the biomechanical advantage of LLIF over TLIF in maintaining disc height, none of the patients in our cohort had symptomatic complications or implant-related failures. Hence, TLIF, as it incorporates posterior decompression, remains a safe and reliable technique despite the potential for greater disc height loss.

Interbody fusion procedures, namely, posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), and lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF), aim to stabilize the fixed segments and achieve appropriate disc height and ultimately fusion of the desired vertebral segments [1]. Although the principle behind all of these procedures is the same, there are certain advantages and disadvantages to each [2–5]. While much of this has already been explored, in the literature there is a lack of studies comparing postoperative disc height loss following these procedures.

Minimal disc height loss can naturally occur due to mechanical loading, which allows settling of the cage or the entire construct as the patient becomes mobile after surgery. This natural occurrence is facilitated by the polyaxial screw heads [6]. However, it becomes a concern when there is cage subsidence adding to the disc height loss [7]. Such disc height loss indicates foraminal narrowing, which could potentially cause exiting nerve root compromise.

Since posterior decompression is usually performed as part of the PLIF or TLIF procedure, this foraminal narrowing would not be expected to cause many symptoms [8]. However, in the case of LLIF, be it oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF) or direct lateral interbody fusion (DLIF), especially when posterior decompression is not performed, recurrence or de novo radicular symptoms could occur [9]. To obtain a better understanding of this and to analyze whether it is a procedure-specific or universal phenomenon, we retrospectively compared disc height for up to 1 year following TLIF and LLIF procedures.

After obtaining institutional review board approval, electronic records of patients who underwent single- or multi-level TLIF and LLIF along with posterior stabilization for degenerative conditions during 2014–2018 were retrospectively reviewed. We excluded patients who were operated on for trauma, tumor, and infectious pathologies. Only those patients whose preoperative and postoperative follow-up radiographs for up to 1 year were available for analysis were shortlisted. Among those, we excluded patients demonstrating signs of radiological non-union and who required a revision procedure during our follow-up period.

Among the included cases, the indications for TLIF and LLIF were the same, namely, degeneration, stenosis, and instability, except that LLIF was preferred whenever sagittal correction was required. Patients in whom TLIF using a single bullet cage was performed predominantly, with or without an additional posterolateral fusion (PLF) at a different level, formed group 1 (Fig. 1). Among these patients, the most common reason for additional fixation and PLF at an adjacent level was to avoid progression of identified radiological early degeneration that could result in adjacent segment problems. Patients in whom LLIF using a wide-bodied cage was performed predominantly, with or without an additional TLIF at a different level, formed group 2 (Fig. 2). Here, the additional TLIF was mostly at the L5–S1 level as the anatomy of L5–S1 does not favor conventional LLIF.

All procedures were performed by a single senior surgeon and based on established protocols. TLIF was performed through a midline incision, midline laminectomy, facetectomy, removal of ligamentum flavum, mobilization of neural elements, discectomy, preparation of endplates, and finally bone grafting and cage placement. Here, the cage size was determined using trial cages during the preparation of endplates. LLIF was performed through a left-sided approach when patient was in the lateral decubitus position. The retroperitoneal space was approached, and the left psoas muscle was either retracted, in the case of OLIF to approach the oblique corridor between aortoiliac vessels and the psoas muscle, or spilt, in the case of DLIF. This was followed by annulotomy, discectomy, and release of the cartilaginous endplate and contralateral annulus, using a wide Cobb. Sequential trailing using a bullet distractor determined the appropriate size of cage to be placed and the cage was placed along with adequate bone graft. For the second stage, the patient was positioned as usual for the posterior approach and posterior instrumented stabilization was performed along with decompression wherever deemed necessary.

The demographic characteristics of both groups were tabulated. Using true lateral view X-ray images, their pre- and postoperative global (L1–S1) lordosis, construct length, and number of TLIF or LLIF cages in each patient was noted. Then, each cage level was analyzed independently. Only those levels that showed neutral endplates for carrying out the measurements in all required true lateral view X-rays were selected. We excluded levels demonstrating subsidence or endplate violation intraoperatively and levels with hybrid LLIF cages that incorporated screws within.

The dimensions (length, breadth, height, and lordosis) of the cages used in both groups were noted from the operative records. Disc height measurements of all of the included levels in both groups were performed digitally from preoperative, immediate postoperative, and follow-up (1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year) true lateral view standing radiographs, as previously described [10]. Briefly, the anterior disc height (ADH) was measured as the distance between the anteriormost points of the upper and lower endplates, excluding osteophytes, if any, and similarly, the posterior disc height (PDH) as the distance between the posteriormost points of the upper and lower endplates. These points were accurately reproduced in the corresponding follow-up radiographs in order to capture any increase or decrease in the disc height. The mean disc height (MDH) was derived using the following formula: (ADH+PDH)/2. The disc space angle (DSA) was measured as the angle between two lines, each connecting the anteriormost to the posteriormost point of each of the endplates. All digital measurements were performed by a single surgeon and saved in our picture archiving and communication system, which were later confirmed by the senior surgeon.

Preoperative disc measurements (ADH, PDH, MDH, and DSA) of the two groups were compared to evaluate whether the groups were matched. Preoperative disc measurements were compared to corresponding postoperative disc measurements in each group to quantify the amount of increase in disc height and variation in DSA. Postoperative and follow-up disc measurements were compared between the groups to identify statistically significant differences. In addition, the amount of disc height loss at final follow-up was compared between the groups.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism ver. 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). We used Student t-test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A probability value “p” of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study with reference number 2019/00196 was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board, National Healthcare Group, Singapore, and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the latest version of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent from individual patients was waived because of the retrospective design of this study.

A total of 46 consecutive patients (age, 64.1±8.9 years; male patients, 22; female patients, 24) with 70 cage levels adhering to our selection criteria were selected. The sample was divided into group 1 or the TLIF group and group 2 or the LLIF group and each cage level was analyzed independently. Both groups consisted of different sets of patients who were operated on by the same surgeon. Age, sex, and construct length of the two groups were matched. There were 35 selected cage levels in each group. The overall numbers of cages in each of the lumbar levels from L1 to S1 in both groups were tabulated (Table 1).

The preoperative levels of global lordosis of the TLIF group (39.7°±14.1°) and LLIF group (40.2°±10°) were statistically similar (p=0.88). Cage dimensions including height, length, breadth, and lordosis were also tabulated (Table 1). It is known that LLIF cages are larger in length and breadth than TLIF bullet cages; however, cage heights of the selected samples were similar between the two groups (TLIF group: 10.1±1 mm; LLIF group: 9.6±1.2 mm; p=0.09). Disc space measurements including ADH, PDH, MDH, and DSA were all statistically similar between the groups.

Given that the groups were similar, with the exception of their cage dimensions, we proceeded to compare the postoperative and follow-up parameters (Table 2). We found that the amounts of increase in disc height after surgery when compared to preoperative height in both TLIF (2.75±2.3 mm) and LLIF (3.24±2.2 mm) groups were similar (p=0.35). Postoperative global lordosis and other disc space measurements (ADH, PDH, MDH, and DSA) were also found to be similar between the groups. The same was observed at 1-month follow-up.

However, by 3 months, the MDH of the TLIF group was found to be significantly less (7.49±1.5 mm) than that of the LLIF group (8.29±1.6 mm, p=0.03). This disc height loss appeared to increase over time and, by 6 months, all of the disc height measurements including ADH, PDH, and MDH of the TLIF group were significantly less than those of the LLIF group (Fig. 3). The same was observed at 1-year follow-up.

To analyze the amount of disc height lost at final follow-up, we measured the difference between the postoperative MDH and the 1-year MDH of the two groups separately. It was found that both groups demonstrated significant disc height loss; however, the TLIF group demonstrated greater loss (2.30±1.3 mm) than the LLIF group (0.89±1.1 mm). This difference was found to be statistically significant (p<0.0001). However, none of the patients had signs of implant loosening, non-union, recurrence, or de novo radicular symptoms in either group.

Disc height loss is widely discussed in the literature in relation to degenerative disc disease [11]. It occurs due to the mechanical forces acting on the disc over many years, eventually leading to foraminal narrowing and nerve impingement [11,12]. These mechanical forces remain constant as long as there is weight-bearing and mobility, even after a fusion procedure, until adequate bony fusion occurs [13]. While the presence of an interbody cage or the posterior construct can act against the compressive forces and offer stability, the endplate or the polyaxial construct might yield to the forces, leading to disc height loss [14].

Postoperative disc height loss is often considered to be due to cage subsidence. However, we noted disc height loss even in those patients who did not demonstrate radiological subsidence. For this reason, we considered yielding of the endplates or the polyaxial construct to influence this phenomenon. Various authors described the advantage of wide-bodied LLIF cages to overcome subsidence [15,16], but these have only rarely been assessed with regard to postoperative disc height in comparison to other fusion techniques.

Minimal disc height loss may not be clinically important following TLIF where posterior and foraminal decompression is generally performed as part of the fusion procedure [8]. However, LLIF is a procedure that predominantly depends on the indirect decompression offered by the cage [17]. Disc height loss of any grade could potentially cause nerve impingement following LLIF, especially when posterior decompression is not performed. For this reason, whenever we felt that the endplates or bone were weak, as perceived while preparing the endplates or applying the screws in almost 30% of our cases, posterior decompression was added to the LLIF procedure. Hence, in both of the selected groups, despite the disc height loss, there were no cases of recurrence or de novo radicular symptoms.

Our results on comparing TLIF with LLIF showed that LLIF is better at maintaining disc height throughout the first year after the fusion procedure. This shows the biomechanical advantage of LLIF cages, which not only rest on the thinner central area of the endplate, but also occupy the thicker periphery, offering sagittal correction and making a stronger bone–cage–bone interface [18]. Since fusion occurs between 6 months and 1 year after performance of the fusion technique, there may not be any further loss of disc height once the fusion mass consolidates, unless there is non-union or construct failure, which we did not encounter in our cohort; hence, we felt it is not ideal to assess this phenomenon for longer periods [19,20].

Being a retrospective study, there are a few methodological shortcomings. With a limited cohort, the power of the study may be limited in terms of the ability to draw definitive conclusions. We also did not assess bone mineral density, which may have influenced disc height loss due to osteoporosis. Moreover, both TLIF and LLIF groups included some patients with additional fixation to assessed levels, which may have contributed to the stability or instability of the rest of the construct and could have influenced disc height loss. In addition, implant-related factors including width or length of the pedicle screw relative to the size of the vertebral body, size of the cage relative to the disc height, position of the cage in the disc space, and severity of preoperative degeneration were not assessed and may have contributed to the measured disc height loss. Since we excluded patients without true lateral view X-rays for analysis, this may have led to underestimation of the rate of disc height loss. Moreover, we did not use a computed tomography scan to evaluate disc height loss, which would have been more empirical. Despite these limitations, we believe that our results provide valuable insights into early disc height loss as a potential complication which physicians need to be aware following lumbar fusion procedures.

We retrospectively compared disc height for up to 1 year following TLIF and LLIF procedures. In our sample, disc height loss occurred following both procedures, but it was more pronounced following TLIF. Even so, there were no recurrent symptoms due to the disc height loss in the TLIF group because posterior decompression was generally performed. While our findings highlight the biomechanical advantage of wide-bodied LLIF cages over TLIF cages in maintaining disc height, it was also observed that the TLIF procedure, as it incorporates posterior decompression, remains a safe and reliable technique despite the potential for greater disc height loss.

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Notes

Author Contributions

AKKP: concept, design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and approval of final version; TLTS: concept, design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, and approval of final version; MT: concept, design, interpretation of data, review, and approval of final version; JYLO: concept, design, interpretation of data, review, approval of final version, and supervision.

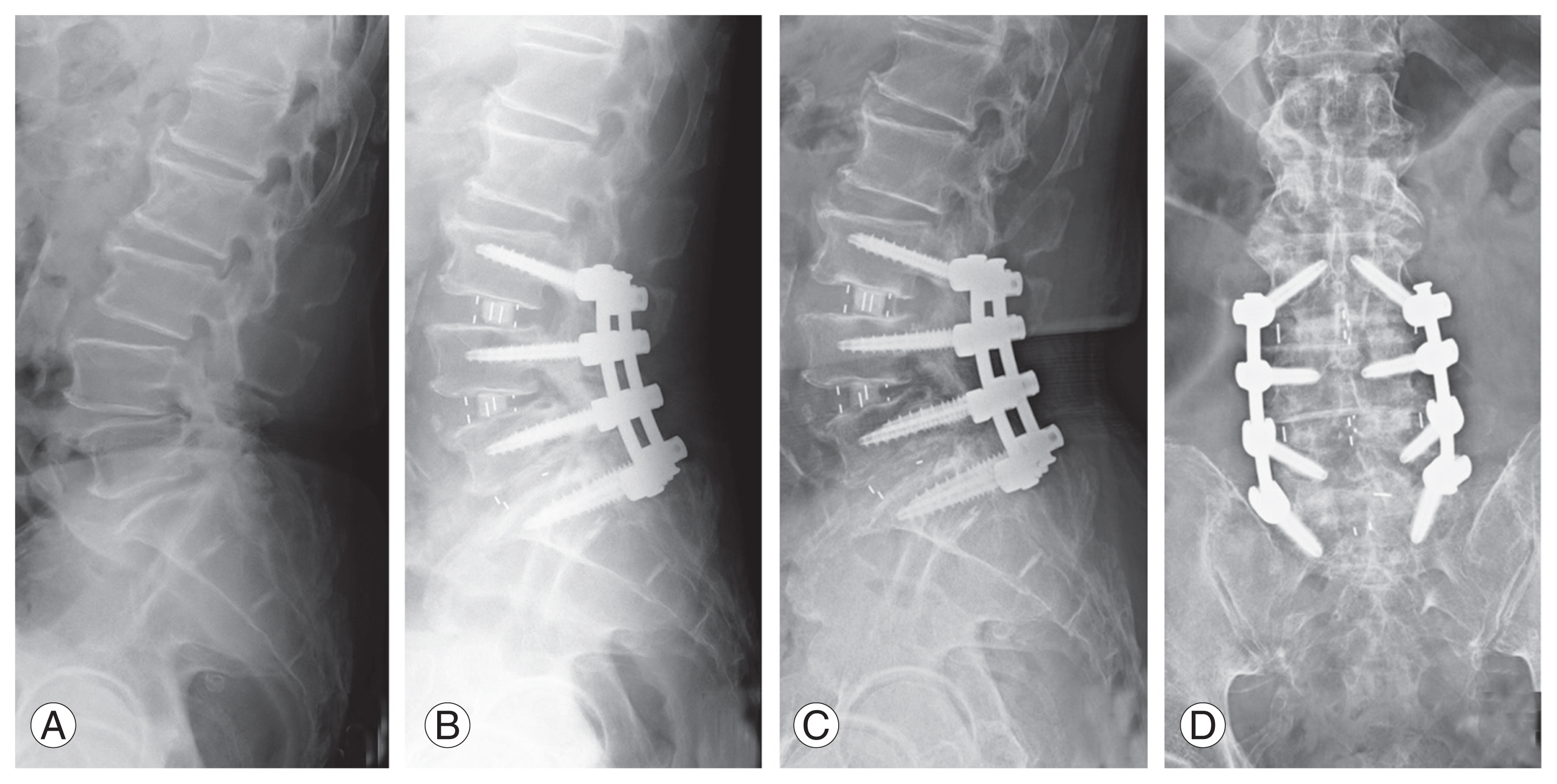

Fig. 1

Representative lateral view X-ray images of a patient from group 1 who underwent L4–L5 transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. (A) Preoperative image. (B) Postoperative image. (C, D) Final follow-up images, lateral and anteroposterior views.

Fig. 2

Representative lateral view X-ray images of a patient from group 2 who underwent L3–L5 lateral lumbar interbody fusion and L5–S1 transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. (A) Preoperative image. (B) Postoperative image. (C, D) Final follow-up images, lateral and anteroposterior views.

Fig. 3

Variation in mean disc height from preoperative to final follow-up. TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion; LLIF, lateral lumbar interbody fusion; Preop, preoperative; Postop, postoperative.

Table 1

Patient characteristics

Table 2

Postoperative follow-up measurements

References

1. Derman PB, Albert TJ. Interbody fusion techniques in the surgical management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017;10:530–8.

2. Fleege C, Rickert M, Rauschmann M. The PLIF and TLIF techniques: indication, technique, advantages, and disadvantages. Orthopade 2015;44:114–23.

3. Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, Seex K, Rao PJ. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI-TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. J Spine Surg 2015;1:2–18.

4. Lee N, Kim KN, Yi S, et al. Comparison of outcomes of anterior, posterior, and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery at a single lumbar level with degenerative spinal disease. World Neurosurg 2017;101:216–26.

5. Zhu G, Hao Y, Yu L, Cai Y, Yang X. Comparing stand-alone oblique lumbar interbody fusion with posterior lumbar interbody fusion for revision of rostral adjacent segment disease: a STROBE-compliant study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12680.

6. Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC, Apfelbaum RI. Axially dynamic implants for stabilization of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery 2006;59(4 Suppl 2): ONS378–88.

7. Malham GM, Parker RM, Blecher CM, Seex KA. Assessment and classification of subsidence after lateral interbody fusion using serial computed tomography. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;23:589–97.

8. Formby PM, Kang DG, Helgeson MD, Wagner SC. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in patients with osteoporosis. Global Spine J 2016;6:660–4.

9. Bocahut N, Audureau E, Poignard A, et al. Incidence and impact of implant subsidence after stand-alone lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:405–10.

10. Kaliya-Perumal AK, Soh TL, Tan M, Oh JY. Factors influencing early disc height loss following lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J 2020;14:601–7.

11. Jarman JP, Arpinar VE, Baruah D, Klein AP, Maiman DJ, Muftuler LT. Intervertebral disc height loss demonstrates the threshold of major pathological changes during degeneration. Eur Spine J 2015;24:1944–50.

12. Oh CH, Yoon SH. Whole spine disc degeneration survey according to the ages and sex using Pfirrmann disc degeneration grades. Korean J Spine 2017;14:148–54.

13. Kim Y. Prediction of mechanical behaviors at interfaces between bone and two interbody cages of lumbar spine segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1437–42.

14. Adam C, Pearcy M, McCombe P. Stress analysis of interbody fusion: finite element modelling of intervertebral implant and vertebral body. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2003;18:265–72.

15. Marchi L, Abdala N, Oliveira L, Amaral R, Coutinho E, Pimenta L. Radiographic and clinical evaluation of cage subsidence after stand-alone lateral interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;19:110–8.

16. Yuan W, Kaliya-Perumal AK, Chou SM, Oh JY. Does lumbar interbody cage size influence subsidence?: a biomechanical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45:88–95.

17. McAfee PC, Shucosky E, Chotikul L, Salari B, Chen L, Jerrems D. Multilevel extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) and osteotomies for 3-dimensional severe deformity: 25 consecutive cases. Int J Spine Surg 2013;7:e8–19.

18. Pimenta L, Turner AW, Dooley ZA, Parikh RD, Peterson MD. Biomechanics of lateral interbody spacers: going wider for going stiffer. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:381814.