|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 12(1); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

To compare minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MI-TLIF) outcomes in primary and revision surgeries.

Overview of Literature

Revision spinal fusion is often associated with an increased risk of approach-related complications. Patients can potentially benefit from the decreased approach-related morbidity associated with MI-TLIF.

Methods

Sixty consecutive MI-TLIF patients (20 failed back [Fa group], 40 primary [Pr group]) who underwent surgery between January 2011 and May 2012 were reviewed after Institutional Review Board approval to compare operative times, blood loss, complications, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores, and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores for back and leg pain before surgery and at the last follow-up.

Results

Nineteen revision surgeries were compared with 36 primary surgeries. One failed back and four primary patients were excluded because of inadequate data. The mean follow-up times were 28 months and 24 months in the Pr and Fa groups, respectively. The mean pre- and postoperative ODI scores were 53.18 and 20.23 in the Pr group and 52.01 and 25.72 in the Fa group, respectively (ODI percentage change: Pr group, 60.36%┬▒29.73%; Fa group, 69.32%┬▒13.72%; p=0.304, not significant). The mean pre- and postoperative VAS scores for back pain were 4.77 and 1.75 in the Pr group and 4.1 and 2.0 in the Fa group, respectively, and the percentage changes were statistically significant (VAS back pain percentage change: Pr group, 48.78┬▒30.91; Fa group, 69.32┬▒13.72; p=0.027). The mean pre- and postoperative VAS scores for leg pain were 6.52 and 1.27 in the Pr group and 9.5 and 1.375 in the Fa group, respectively (VAS leg pain percentage change: Pr group, 81.07┬▒29.39; Fa group, 75.72┬▒15.26; p=0.538, not significant). There were no statistically significant differences in operative time and estimated blood loss and no complications.

The advent of minimally invasive spine surgery has enabled surgeons to perform complex spinal procedures for varied indications while leaving behind the smallest surgical footprint [1]. Minimally invasive techniques in lumbar interbody arthrodesis have undergone continuous evolution of the procedural approaches and instrumentation. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MI-TLIF) techniques have been reported to reduce the iatrogenic soft tissue injury that occurs with muscle stripping and retraction during routine spinal exposure [2]. The potential advantages of minimally invasive procedures include less soft tissue injury, decreased blood loss, decreased hospital stay, and early recovery, which have led to clinical outcomes similar to those of open procedures [23]. Revision patients present a surgical challenge because of altered anatomical landmarks, avascular scars from previous surgery, and epidural fibrosis, which have been associated with increased risk of dural tears (DTs), wound-related complications, and neural injury [4]. Patients in these cases can potentially benefit from the decreased approach-related morbidity (dissection through scar tissue) provided by MI-TLIF.

A primary MI-TLIF is itself a challenging technique and is associated with a significant learning curve [5]. Adaptation of minimally invasive techniques in revision surgeries and their effects on the clinical outcome and incidence of perioperative complications in such scenarios needs further exploration. With this background, the purpose of this study was to compare the operative results, clinical outcomes, and perioperative complications after primary and revision MI-TLIF.

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from 55 consecutive patients who underwent the MI-TLIF procedure between January 2011 and May 2012. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Bombay Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, India (IRB approval no., BhIRB No: 1001). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The analysis included 36 primary surgeries (Pr group) and 19 revision surgeries (failed back, Fa group) involving all patients who required decompression and instrumented fusion for stenosis and instability demonstrated on magnetic resonance images and dynamic radiographs. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

The patients under general anesthesia were positioned prone on a spinal surgery radiolucent table. The entire operation can be divided into two critical steps: (1) decompression, discectomy, bone-grafting, and cage insertion for interbody fusion surgical access obtained using a tubular retraction system (e.g., Quadrant; Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA) and (2) percutaneous placement of pedicle screws and rods (various companies).

The approach was usually performed at the side with preoperative radicular symptoms. If both sides were symptomatic, then the most symptomatic one was preferred. If both sides were equally symptomatic, then the decision was based on the surgeon's preference. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a guidewire was advanced and centered over the facet joint. Sequential dilators were inserted over the guidewire while confirming the target site under fluoroscopy. A 22-mm diameter tubular retractor of appropriate length was used as the working channel. Under microscopic visualization, facetectomy, decompression, discectomy, and endplate preparation were performed through the tube. Sufficient autologous bone graft obtained from the removed facet was packed in the anterior third of the disc space. A cage of appropriate size was inserted. Screws and rods were placed percutaneously on both sides.

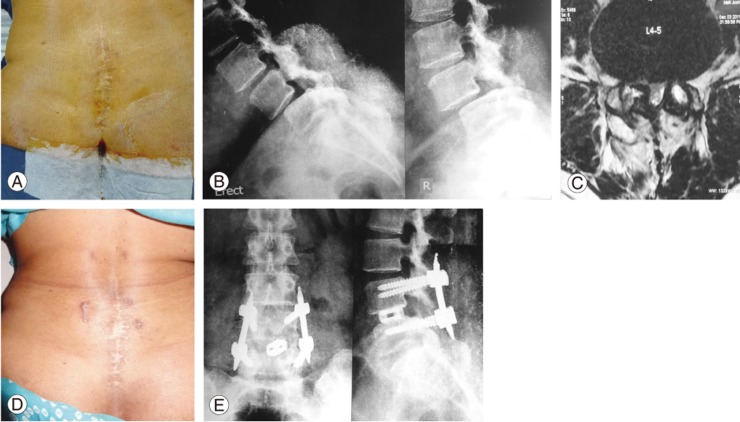

Careful attention to the altered anatomy as a result of previous exposure was of paramount importance in limiting the concerns for potential neural injury. One of the crucial steps in approaching patients who had undergone previous wide laminectomy was the safe placement of the guidewire and working channel to avoid inadvertent dural penetration. The guidewire was directed more laterally on the facet to ensure that it was not near vital structures and previous iatrogenic bony defects. Procuring bone graft for fusion has been an issue in revision surgeries. The bone provided by excision of facets and excision of remaining lamina served as the graft. We felt that the bone thus harvested was adequate and there was no need for additional graft harvesting. Figs. 1AŌĆōE and 2AŌĆōF illustrate two case examples of the technique.

The data collected for analysis were age, sex, preoperative diagnosis, operating time, intraoperative blood loss, clinical and radiographic results, and complications. Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores for back and leg pain were collected from the patients preoperatively, postoperatively, and at the last follow-up.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as means┬▒standard error of the means. Student t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables. The percentage change in pain (VAS for leg and back pain) and percentage change in disability (ODI) were calculated according to the following equation: percentage change=(postoperative VAS or ODIŌĆōpreoperative VAS or ODI)/preoperative VAS or ODI├Ś100, where the postoperative values were those obtained at the 2-year follow-up. All p-values of <0.05 were accepted as indicating statistical significance.

The mean age of the patients was 50.61 years with a male-to-female ratio of 1.8:1 in the Fa group and 49.52 years with a male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1 in the Pr group. The mean follow-up was 28 months (range, 20ŌĆō38 months) and 24 months (range, 18ŌĆō28 months) in the Pr and Fa groups, respectively. The mean pre- and postoperative ODI scores were 53.18 and 20.23 in the Pr group and 52.01 and 25.72 in the Fa group, respectively, and the percentage change was similar between the groups (p=0.304). The mean pre- and postoperative VAS scores for back pain were 4.77 and 1.75 in the Pr group and 4.1 and 2.0 in the Fa group, respectively. The mean pre- and postoperative VAS scores for leg pain were 6.52 and 1.27 in the Pr group and 9.5 and 1.375 in the Fa group, respectively. The percentage change in VAS scores for back pain was statistically significant (p=0.027), whereas that in VAS scores for leg pain was not statistically significant (p=0.538). The mean blood losses were 110 mL and 100 mL in the Pr and Fa groups, respectively. The mean operative times were 3.4 and 3.2 hours in the Pr and Fa groups, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in operative times and estimated blood losses (p=0.406). Dynamic X-rays were used to demonstrate spinal instability. The indication for failed-back MI-TLIFs was iatrogenic instability following laminectomy. The indications for primary MI-TLIFs included degenerative listhesis (n=19), lytic listhesis (n=12), central herniated nucleus pulposus (n=3), and degenerative disc disease (n=2). No complications were observed in either groups. The parameters studied are summarized in Table 2.

Among the spectrum of failed backs, revision surgical treatment is a reasonable option for select conditions, which include recurrent disc herniation, infection, pseudoarthrosis, hardware failure, flatback syndrome, iatrogenic instability, or adjacent segment degeneration [6]. Iatrogenic instability was the primary indication for failed-back MI-TLIF revision surgeries. Historically, revision surgery with stabilization and decompression has often been found to be most successful in failed backs having spinal instability following destructive laminectomies/discectomies. On the other hand, surgical intervention in these abject situations has also been found to be associated with a high risk of perioperative complications [47]. Most of these complications are approach and access related. The primary MI-TLIF procedure has shown significant approach-related advantages, including less blood loss, less muscle damage, and less perioperative morbidity [3]. To determine whether these advantages could be translated to revision surgeries was the objective of this study. With this background, we compared the outcomes of MI-TLIF to attain the goals of stabilization and decompression between selected patients with failed backs and patients who underwent primary surgeries.

Access to the spine in revision surgery is more technically arduous than that in primary surgery and is associated with higher risk of complications, particularly that of nerve root injury and incidental durotomy [8]. The scar tissue of previous posterior surgery offers a relatively avascular bed for new bone graft, and repeat surgery through previous scars has been found to be frequently associated with permanent distressing dysesthesias [9]. Although the anterior approach has been considered to be attractive for rescue of failed posterior fusions, approach-related potential complications have been daunting [10]. The alternative, i.e., open transforaminal interbody fusion (O-TLIF) has several inherent disadvantages in revision spine surgeries. The O-TLIF technique requires tissue dissection through the scar and lateral to the facet joints to gain access to the disc space and provide an ideal orientation for optimal screw trajectory. There are only a handful of studies in the literature that have explored open TLIF as an option in revision spine surgery. In a series of 54 consecutive patients, including eight revision cases, undergoing TLIF, Hackenberg et al. [11] reported an average blood loss of 485 mL, with one patient (1.85%) suffering an intraoperative nerve root injury without motor deficit. In a retrospective review of 24 patients that included 10 patients (42%) who had undergone previous spine surgery, Salehi et al. [12] reported an average estimated blood loss of 1,400 mL, with one patient suffering a transient left foot drop. Potter et al. [13] retrospectively reviewed the outcomes in 100 patients and found the incidence of DTs to be significantly higher for revision procedures than that for primary procedures (6.5%/level versus 3.7%/level, p=0.07). In a series of 531 patients, Tormenti et al. [14] reported a 1.75 times higher likelihood of perioperative complications in patients who had undergone revision surgery than that in patients who had undergone primary surgery, with the risk of an inadvertent DT 1.75 times higher in the revision surgery cohort. More recently, in a retrospective series of 187 patients that included 114 patients undergoing revision surgery, Khan et al. [15] reported a 28.9% intraoperative or postoperative complication rate.

With a previous conventional midline access, the intermuscular plane of Wiltse remains unviolated in revision surgeries. The MI-TLIF technique appears to be a better option in such situations because it uses this intact paraspinal Wiltse approach for access to the disc space and placement of pedicle screws [16]. The notable perceived access-related advantages of the versatile MI-TLIF technique pertaining to revision surgeries include use of relatively preserved anatomical landmarks (facet joints), minimal muscle dissection and devascularization, and minimal need for working through difficult scar tissue from the previous procedure (transforaminal approach is lateral to the usual midline scar tissue). This is important because it is believed that dissection in areas of unscarred tissue followed by access to scarred regions can potentially avoid dural entry resulting from adhesions in the epidural space and dural scarring [17]. In a meta-analysis that included 11 randomized and nonrandomized studies comparing the outcomes of minimally invasive and conventional O-TLIF for degenerative lumbar diseases, the authors found that MI-TLIF was associated with lesser blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and better functional outcomes than O-TLIF [3]. In contrast, significantly increased intraoperative radiation exposure was observed in MI-TLIF. The operative times, complication rates, and reoperation rates were similar between the two groups. Similar findings were reported in a more recent updated systematic reviews [1819]. Whether these advantages seen in primary surgeries are applicable to revision surgeries has not been reported in the literature. In our study, we explored the implications of applying the MI-TLIF technique to revision surgeries.

Only a few studies have reported the outcomes of MI-TLIF in failed backs. Wang et al. [20] studied the outcomes of MI-TLIF (n=25) and O-TLIF (n=27) as revision surgery for patients who previously underwent open discectomy and decompression. The authors in that study could not find any statistical differences in operating times, preoperative and latest back (or leg) pain VAS scores, or preoperative and latest ODI scores between the two groups. Their statistical evaluation showed a highly significant decrease in the intraoperative and postoperative blood losses (p=0.01) in the MI-TLIF group. There was a significant difference in the X-ray exposure times between the groups, with an average of 73 seconds in the MI-TLIF surgery and 39 seconds in the O-TLIF surgery. The mean back pain VAS score was lower in the MI-TLIF group than that in the O-TLIF group at the second day after surgery. Three cases of small DTs were observed in the MI-TLIF group, which recovered uneventfully with tight closure of the overlying fascia intraoperatively. There were five cases of DTs and two cases of superficial wound infection in the O-TLIF group. One case of nonunion was observed in both groups. In our study, the clinical outcomes were comparable between the Pr and Fa groups except for the percentage change in VAS for back pain, which showed a significant improvement in the failed backs. In a recent study that evaluated revision lumbar surgery in elderly patients with symptomatic pseudarthrosis, adjacent segment disease, or same-level recurrent stenosis, Adogwa et al. [21] found more significant improvements in VAS for back pain than VAS for leg pain; this was similar to our study findings.

In a recent study, Wong AP et al. [22] reported on the intraoperative and perioperative complication rates following MI-TLIF in 513 patients. The study included 130 patients (25.3%) who had previously undergone a lumbar surgery and required a revision MI-TLIF and 383 patients (74.7%) undergoing their first lumbar surgery. After analysis, no statistically significant difference was observed in the rate of durotomy between revision and multilevel surgeries. In total, 18 patients (4.7%) received durotomy as a first-time surgery and eight patients (6.2%) received revision surgery. None of the patients required any intervention for the dural leak, which resolved with bed rest. A statistically significant increase in the infection rate was observed in the revision MI-TLIF patients, but all the infections (7 of 513) were perioperative medical infections. The only surgical site infection seen in the series was in a patient undergoing primary MI-TLIF surgery. In addition, the authors found no significant difference in the complication rates stratified according to presenting diagnosis. There were no complications observed in our study in either of the groups; this can be attributed to the fact that the senior author had been performing MI-TLIF surgeries for 5 years prior to initiation of this study. Hence, most of the learning curve for the procedure had already been traversed. Recent studies [523] have found that the initial learning curve significantly affected both the complication rate and clinical outcomes, with the results improving over time. The estimated blood losses and operative times were similar between the groups.

The inherent MI-TLIF technique is particularly suitable for selectively indicated revision surgeries because it exploits the intact paramedian corridor of an operated patient's anatomy. The symptoms of failed back that stem from instability can be addressed through minimal access instrumentation and fusion, with no need for midline exploration. The authors recommend MI-TLIF in selected cases of revision surgery.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Mannion R. Spine surgery: minimally invasive spinal surgery: does size matter? Nat Rev Neurol 2012;8:363ŌĆō365. PMID: 22664786.

2. Karikari IO, Isaacs RE. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a review of techniques and outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(26 Suppl): S294ŌĆōS301. PMID: 21160393.

3. Tian NF, Wu YS, Zhang XL, Xu HZ, Chi YL, Mao FM. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a meta-analysis based on the current evidence. Eur Spine J 2013;22:1741ŌĆō1749. PMID: 23572345.

4. Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:626ŌĆō633. PMID: 8852320.

5. Lee JC, Jang HD, Shin BJ. Learning curve and clinical outcomes of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: our experience in 86 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1548ŌĆō1557. PMID: 22426447.

6. Slipman CW, Shin CH, Patel RK, et al. Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med 2002;3:200ŌĆō214. PMID: 15099254.

8. Cammisa FP Jr, Girardi FP, Sangani PK, Parvataneni HK, Cadag S, Sandhu HS. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2663ŌĆō2667. PMID: 11034653.

9. Sihvonen T, Herno A, Paljarvi L, Airaksinen O, Partanen J, Tapaninaho A. Local denervation atrophy of paraspinal muscles in postoperative failed back syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:575ŌĆō581. PMID: 8484148.

10. Schwender JD, Casnellie MT, Perra JH, et al. Perioperative complications in revision anterior lumbar spine surgery: incidence and risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:87ŌĆō90. PMID: 19127166.

11. Hackenberg L, Halm H, Bullmann V, Vieth V, Schneider M, Liljenqvist U. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a safe technique with satisfactory three to five year results. Eur Spine J 2005;14:551ŌĆō558. PMID: 15672243.

12. Salehi SA, Tawk R, Ganju A, LaMarca F, Liu JC, Ondra SL. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: surgical technique and results in 24 patients. Neurosurgery 2004;54:368ŌĆō374. PMID: 14744283.

13. Potter BK, Freedman BA, Verwiebe EG, Hall JM, Polly DW Jr, Kuklo TR. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: clinical and radiographic results and complications in 100 consecutive patients. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:337ŌĆō346. PMID: 16021015.

14. Tormenti MJ, Maserati MB, Bonfield CM, et al. Perioperative surgical complications of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a single-center experience. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;16:44ŌĆō50. PMID: 21999389.

15. Khan IS, Sonig A, Thakur JD, Bollam P, Nanda A. Perioperative complications in patients undergoing open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion as a revision surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;18:260ŌĆō264. PMID: 23259540.

16. Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, Foley KT. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:S1ŌĆōS6. PMID: 15699793.

17. Elgafy H, Vaccaro AR, Chapman JR, Dvorak MF. Rationale of revision lumbar spine surgery. Global Spine J 2012;2:7ŌĆō14. PMID: 24353940.

18. Khan NR, Clark AJ, Lee SL, Venable GT, Rossi NB, Foley KT. Surgical outcomes for minimally invasive vs open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2015;77:847ŌĆō874. PMID: 26214320.

19. Phan K, Rao PJ, Kam AC, Mobbs RJ. Minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for treatment of degenerative lumbar disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2015;24:1017ŌĆō1030. PMID: 25813010.

20. Wang J, Zhou Y, Zhang ZF, Li CQ, Zheng WJ, Liu J. Minimally invasive or open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion as revision surgery for patients previously treated by open discectomy and decompression of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 2011;20:623ŌĆō628. PMID: 20927557.

21. Adogwa O, Carr RK, Kudyba K, et al. Revision lumbar surgery in elderly patients with symptomatic pseudarthrosis, adjacent-segment disease, or same-level recurrent stenosis: part 1. two-year outcomes and clinical efficacy: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;18:139ŌĆō146. PMID: 23231354.

22. Wong AP, Smith ZA, Nixon AT, et al. Intraoperative and perioperative complications in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a review of 513 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22:487ŌĆō495. PMID: 25700243.

Fig.┬Ā1

(A) Preoperative midline scar. (B) Dynamic radiographs demonstrating instability. (C) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging showing stenosis. (D) Postoperative scar of MI-TLIF in the background of the midline scar. (E) Postoperative radiology of MI-TLIF. MI-TLIF, minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion.

Fig.┬Ā2

(A) Preoperative midline hypertrophic scar. (B) Preoperative MRI showing retrolisthesis. (C) Preoperative computed tomography scan showing canal stenosis. (D) Postoperative scars of minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in the background of hypertrophic scar. (E) Postoperative radiograph. (F) Postoperative MRI showing old midline scar with relatively intact paraspinal musculature. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.