|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 15(6); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

To share our experience of multimodal intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM) used in Sakra World Hospital, Bengaluru in various spine surgeries.

Overview of Literature

The development of new onset postoperative neurological deficits can be completely avoided. In order to avoid these, IONM has become a standard of care in recent times for early detection and manipulation of the surgical procedure to prevent postoperative neurological deficits.

Methods

This retrospective study was performed on 408 patients who had undergone spine surgeries with IONM during April 2014 to March 2020 at a single center. The operative report, anesthesia record, and IONM were reviewed. All the patients were reassessed for postoperative neurological deficits in the postoperative period and followed up based on the intraoperative findings and neurological deficits for 4 weeks. Signal changes in IONM were reviewed, and the obtained results were further categorized into true positive, true negative, false positive, or false negative. If changes were observed during the IONM, the patients were managed as per the algorithm.

Results

Of the 408 patients being monitored continuously during the intraoperative period, 38 showed changes in recordings, 28 developed postoperative neurological deficits, and one developed neurological deficit without any change in the IONM. Nine patients had transient neurological deficits, and the other 20 had permanent neurological deficits. Overall, the multimodal IONM used in our study had a sensitivity of 96.6%, specificity of 97.4%, a positive predictive value of 73.7%, and a negative predictive value of 99.7%.

Conclusions

Use of decision algorithm and multimodal neuromonitoring consisting of motor evoked potentials, somatosensory evoked potentials, and electromyography complement each other in the detection of neurological injury during the course the surgery, improve intraoperative care, and prevent further damage and morbidity in patients.

Safety is of primary concern in any spine surgery and has become a critical issue in recent times. The development of new onset postoperative neurological deficits needs to be completely avoided if possible. In order to minimize such developments during surgery, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM) has become the standard of care during spinal surgeries, particularly during instrumentation and deformity correction. Structures, such as the spinal cord, nerve roots, plexus, and corresponding vascular elements in and around the spine, are at actual risk for potential damage during the procedure. Thus, the primary aim of IONM is early detection and possible reversal of potential neurological injury to minimize postoperative neurological deficits. This is most important during adult spinal deformity surgeries because 23% of the patients experience some kind of neurological decline in the postoperative period [1].

Numerous IONM modalities are available for monitoring the different aspects of the nervous system (including the central and peripheral nervous systems). Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials (TcMEPs), and spontaneous and triggered electromyography (s-EMG and t-EMG) are the most frequently used modalities. IONM optimization is crucial with a combined interdisciplinary effort among the spine surgeons, anesthetists, and the neurophysiologist [2].

The technique of monitoring the spinal cord was first used in the late 1970s when SSEP was reported during scoliosis surgery [3]. Since then, IONM has evolved, and newer advanced modalities have been developed; however, SSEP remains the principal modality for spinal cord monitoring [4]. SSEP continues to be a simple and reliable method for assessing afferent conduction from the site of peripheral nerve stimulation through the dorsal columns, brainstem, and thalamus to the primary somatosensory cortex. The TcMEPs was initially presented as a single-pulse stimulation technique and was considered highly subtle signal under anesthesia [5]. However, in the early 1990s, multi-pulse stimulation was introduced [6], and various modifications were made to the anesthetic regimens to amplify the ability to monitor TcMEPs. This modality is now being widely used in various spinal surgeries, including deformity correction, degenerative cases, trauma, and tumor resection. Moreover, s-EMG and t-EMG have added advantages in monitoring individual nerve roots and pedicle breach during screw placement. The combined use of SSEPs, TcMEPs, and electromyography (EMG) is advantageous because it combines the strengths of various modalities to obtain a broader evaluation of the spinal cord and roots [6]. Multimodal IONM provides the essential tools for a precise and reliable monitoring technique for evaluating the functional integrity of the spinal cord during various spinal surgeries.

The present study was designed to share our experience of multimodal IONM techniques including TcMEP, SSEP, s-EMG, and t-EMG used in our institute in various spine surgeries.

This retrospective study was performed on 408 patients who underwent spine surgeries with IONM during April 2014 to March 2020 at the Sakra World Hospital, Bengaluru, India. All the patients underwent IONM with SSEPs, TcMEPs, s-EMG, and t-EMG during the surgical procedures. Standard demographic and clinical data were collected from all the enrolled patients. Preoperative Medical Research Council (MRC) grading of all the muscle groups were recorded. The anesthesia protocol and agents used during induction and maintenance were reviewed. The operative report, anesthesia record, and IONM records were reviewed, and the neurological status of the patient was reassessed in the postoperative period; further follow-up was performed as per the intraoperative findings and neurological deficits for 4 weeks.

Signal changes in the IONM were reviewed, and the obtained results were categorized into true positive, true negative, false positive, or false negative [4]. When a patient had significant signal changes intraoperatively accompanied by a new postoperative neurological deficit, the result was considered true positive. Transient neurological deficits were defined as recovery of neurological deficits within 4 weeks of surgery. Permanent neurological deficits were defined as persistent neurological deficits after 4 weeks of surgery. When a patient had baseline intraoperative and postoperative signals with no new postoperative neurological deficit, the result was considered true negative. When there was persistent and significant signal deterioration intraoperatively, but the patient was awakened without neurological deficits, the result was considered false positive. When a patient had postoperative neurological deficits without any change in intraoperative signals, the result was considered false negative. Postoperative neurological deficits were defined as a decrease of >1 in the motor score as per the MRC scale or total loss of sensation.

The total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) technique was used in all the patients. TIVA was maintained with infusion of propofol (100–200 μg/kg/min) and fentanyl (1–2 μg/kg) that were titrated to a bispectral index of 30–40. Muscle relaxants were avoided in all patients except during induction where atracurium (0.5 mg/kg) or succinylcholine (1.5 mg/kg) was used in order to facilitate intubation. Train-of-four was conducted by an anesthetist to ensure that neurophysiological responses were not affected by the neuromuscular blockade. Some patients required arterial line cannulation and continuous invasive blood pressure monitoring. Desflurane (minimum alveolar concentration [MAC] of 0.3) was used in 62 patients with TIVA to facilitate general anesthesia. Proper communication between the anesthesiologist and neurophysiologist was maintained to prevent anesthesia-related alterations during IONM recording.

All the patients were monitored with NIM ECLIPSE version E3 Neuro Monitoring System (Medtronic Xomed, Jacksonville, FL, USA) and later upgraded to Medtronic NIM ECLIPSE version E4 Neuro Monitoring System (Medtronic Xomed).

TcMEPs were recorded bilaterally from the upper and lower extremities, and the muscles were monitored as per the individual patient requirement. Most commonly, the abductor pollicis brevis in the upper limb and tibialis anterior and abductor hallucis longus in the lower limbs were measure. Other muscles that were monitored were the rectus abdominis and the anal sphincter in case of spinal cord tumors, conus lesion, and spinal dysraphism. These myogenic responses were elicited with voltage ranging from 250 to 500 V and an anodal pulse train ranging from 4 to 8. The stimulus was delivered for a brief period (75 μs), with a 1–3-msec interstimulus interval. Corkscrew electrodes were inserted subcutaneously over the motor cortex regions C1–C2 and C3–C4 stimulating montage applied according to International 10–20 System. Alarm criterion is to reduce the amplitude of compound muscle action potential by 50% or more, or to increase the requirement of electrical stimulation to obtain the same potentials.

Cortical SSEPs were elicited using a 200-μsec square-wave electrical pulse stimulating the posterior tibial and median nerves at a rate of 3.27–4.1 Hz, with a stimulation intensity ranging from 10 to 45 mA, bandpass filtered at 30–500 Hz. Averages of 300–500 sweeps were collected as per the signal-to-noise ratio. Cortical potentials were recorded from the subdermal corkscrew electrode placed to Cpz, C3, and C4 and referenced to Fpz (International 10–20 System). Alarm criteria were 50% reduction in the amplitude or 10% increase in the latency.

The s-EMG and t-EMG were used during pedicle screw placement and stimulation of nerve roots and neural structures in the spinal dysraphism and spinal cord tumor excision. The EMG activity was recorded from the upper and the lower limbs using 25-mm paired stainless-steel needle electrodes insulated to within 5 mm of the tip. The threshold used to detect the incorrect screw placement and medial breach was 8 mA in the lumbar region and 6 mA in the thoracic region.

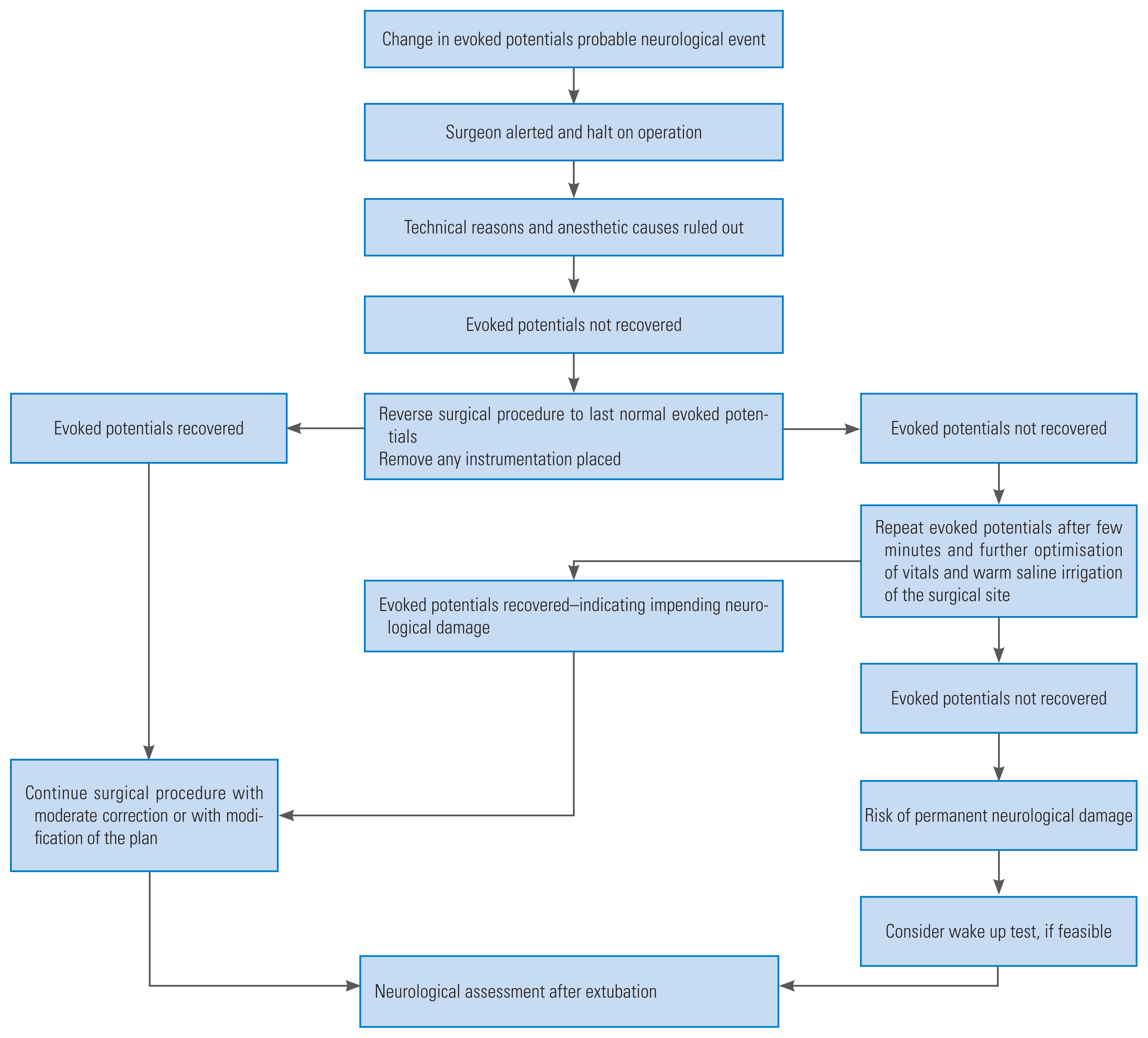

Close collaboration between the anesthetists, neurophysiologist, and surgeons were maintained during the whole procedure. In case of any untoward IONM findings during the surgery, we used to follow the algorithm developed at our institute (Fig. 1). The routine initial check-up in all cases of where change in evoked potentials was observed, included mean arterial pressure of >80 mm Hg and core body temperature of >36.5ºC. Technical glitches with the recording system or owing to dislodgement of the electrodes were also excluded. Other anesthetic problems, such as muscle relaxant, bolus of anesthetic agent, and high dose of inhalational agent, were ruled out before further proceedings.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The requirement for informed consent from individual patients was omitted because of the retrospective design of this study.

The demographic characteristics of the patients that were studied are shown in Table 1. The study included 408 patients (277 men and 131 women) with a mean age of 56 years, ranging from 6 months to 90 years. The various surgeries where IONM was performed are summarized in Table 2.

Of the 408 patients being monitored continuously during the intraoperative period, 29 patients developed postoperative neurological deficits (nine recovered to the preoperative status within 4 weeks postoperatively). Changes in the evoked potentials were observed in 38 patients as per the alarm criteria described previously. Of the 38 patients who showed changes in the recordings, 28 developed postoperative neurological deficits (Figs. 2, 3). One patient with an intramedullary lesion who was operated and did not show any significant IONM changes during the intraoperative period developed quadriparesis during the postoperative period. The patients who developed neurological deficits and changes in intraoperative recordings have been summarized in Table 3. While considering postoperative complications, only one of the 408 patients developed tongue laceration during the intraoperative period.

Overall, the multimodal IONM used in our study had a sensitivity of 96.6%, specificity of 97.4%, positive predictive value of 73.7%, and a negative predictive value of 99.7%. These data have been summarized in Table 4. While considering the groups of the operative procedures where IONM was used, most patients who underwent lumbar interbody fusion and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion had only false positive results, where the sensitivity of detection of postoperative neurological deficits was very low. The remaining diagnostic values of IONM in other groups are as shown in Table 5.

Multimodal IONM provides considerable information during spinal cord surgery. In our study, 408 patients were monitored with multimodal IONM during spinal surgeries and evoked potential changes were present in 38 patients; neurological change was observed in 29 patients in the postoperative period. The sensitivity and specificity of multimodal IONM observed in this study are 96.6% and 97.4%, respectively. The positive predictive value and negative predictive value are 73.7% and 99.7%, respectively. While considering the operative procedures groups, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and lumbar interbody fusion surgeries gave only false positive results because no postoperative deficits were visualized. The sensitivity of IONM was very low in these two surgeries. The rest of the groups showed sensitivity and specificity of almost 100%. All the patients who showed neurological deficits in the postoperative period had evoked potential changes with respect to TcMEPs, except one patient in whom no evoked potential changes were observed during the intraoperative period. Neurological deficits were transient in nine patients, and the rest persisted to have permanent motor deficits. One patient developed tongue laceration related to IONM that subsided with conservative management. Although, there are few IONM-complications, a few reported incidents include tongue laceration, scalp burns at the site of electrode insertion, cardiac arrhythmias, awareness, and jaw fractures [7].

SSEPs were initially very reliable in the guidance in spinal surgeries; however, later, it was reported that its assessment of motor pathway integrity was incongruous, leading to high false negative rates [8–10]. In 2010, Kundnani et al. [8] showed that SSEPs being monitoring had a specificity of 100%; however, the sensitivity was only 51% in patients who underwent idiopathic scoliosis surgery. Deutsch et al. [9] performed SSEP monitoring on 44 patients undergoing anterior thoracic vertebrectomy and showed that SSEPs had a high false negative rate and a sensitivity of 0%. Hilibrand et al. [10] compared TcMEPs and SSEPs in cervical spine surgeries and showed that SSEPs had a sensitivity of 25% and specificity of 100%. Further, many studies have shown that the SSEPs do not have the ability to monitor and detect motor deficits and are associated with a high false negative result [11]. Moreover, SSEPs are not very subtle for detecting nerve root injuries and cannot be used during pedicle screw placement and surgeries involving nerve root traction [12]. Consequently, SSEPs are not being used as the sole monitoring technique during spinal surgeries for the detection of motor deficits.

The stimulation of the motor cortex leads to the generation of compound muscle action potential in the periphery that can be monitored. It is relatively simple, direct, monitoring of the corticospinal tract and has become the monitoring modality of choice in spine surgeries. TcMEPs are shown to have higher sensitivity than SSEPs in the detection of spinal cord damage [10]. The spinal cord is sensitive to blood loss and decreased perfusion during surgery, leading to ischemic changes. In these situations, TcMEPs are inadequate for revealing these ischemic damages [13]. Thus, the two modalities complement each other in providing vast information of the spinal cord being monitored during spinal surgeries. Individual nerve roots and myotomes are also being monitored in our study for additional information using EMG. In this study, patients undergoing spine surgeries underwent multimodal monitoring using TcMEPs, SSEPs, s-EMG, and t-EMGs.

It has become a norm in many of the spine centers across the world to use multimodal IONM performed by experienced neurophysiologists during spine surgeries, mainly for the reduction of neurological complications and improvement in the results during the postoperative period. The spinal cord contains both, the ascending tract and descending tract; therefore, one method is insufficient for monitoring the function of the spinal cord. The multimodal approach is necessary for monitoring the tracts of the spinal cord. In order to facilitate proper communication and understanding in the team, the designed algorithm is constructive in further handling during the surgery if there is any change in the evoked potentials (Fig. 1). The use of multimodal monitoring and the algorithm has increased the ease of surgeons in being more cautious and result in lesser neurological complications. Multimodal monitoring along with algorithm-based management used in the study monitoring the tracts helps in monitoring different parts of the spinal cord during different surgical procedure and eliminates the barrier of different surgeons involve in patient management to acquire uniformity in the final results.

The study analyzed the sensitivity and specificity in general and in individual groups among different spine surgeries. Considering the results, most patients who developed permanent neurological deficits in this study were those undergoing surgery for spinal cord tumor, traumatic fractures, deformity correction, or spinal dysraphism. Chang et al. [14] showed that patients with postoperative neurological deficits had undergone similar surgeries. This study showed results of 96.6% sensitivity and 97.4% specificity, almost similar to that in previous studies on deformity correction [8,15,16]. Is it same when considering the spinal cord tumor surgeries, recent studies have shown that patients undergoing spinal cord tumor surgery will have postoperative neurological deterioration in about 18% to 24.6% [17,18]. TcMEPs improve the neurological outcome in patients undergoing intramedullary tumor surgeries [18]. They also concluded that a long-term follow-up of >3 months was essential for determining the difference between the monitored group and the non-monitored group [18]. In our study, we followed up the patients for about 4 weeks; a long-term follow-up would have minimized the number of patients with permanent neurological deficits in the postoperative period. As recommended in previous studies, the alarm criterion for TcMEPs used in this study was a decline of ≥50% in the amplitude [19–22]. The number of false negative results increase if the alarm criterion is kept at 80% from that at baseline, increasing the specificity, and decreasing the sensitivity further. Despite maintaining a baseline change of 50%, some studies have shown high sensitivity and specificity [11,23]. In contrast, Park et al. [21] have shown that TcMEPs have a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 84% in patients undergoing cervical kyphosis with an alarm criterion of decline in amplitude of 50%. Lee et al. [22] observed TcMEPs changes in 267 patients out of 1,445 patients with an alarm criterion of 60%; however, neurological deficit was visualized only in two patients. Thus, the tendency of alarm criterion is set at 50%–60% where the rate of false negative results would be low, and specificity would be maintained.

A steady state anesthesia protocol is being followed in our institute to avoid any boluses or change in the anesthesia plan. All the patients in the study were maintained with propofol and fentanyl infusion as the primary anesthesia agents. Bispectral index value was maintained at 30–40 in all cases. Desflurane was used as a supplement in 64 patients with a MAC of ≤0.4. TcMEPs are very sensitive to halogenated inhalational anesthetics and muscle relaxants [24]. The halogenated agents suppress the anterior horn cells and consecutively suppress TcMEPs [25]. In our study, desflurane used in low dose among 64 patients showed no depression in TcMEPs monitoring. These inhalational agents have an effect on TcMEPs in a dose-dependent manner [26]. It is widely advocated that intravenous anesthetics be preferred over inhalational anesthetics while neuromonitoring is being considered. However, a low dose inhalational agent does not decrease the amplitude.

This study deals with IONM in spine surgeries in general and has certain limitations. First, the patients with neurological deficits were followed up only for 4 weeks. For better interpretations, additional follow-up of about 1 year would be advantageous. The study includes a wide variety of postoperative neurological deficits, ranging from mild weakness to complete loss of motor and sensory function. This study does not incorporate D-wave monitoring that would optimize the way we analyze corticospinal tracts in spinal cord tumor surgeries [18].

Complete neurological information can be obtained from multimodal neuromonitoring and provides surgeons more diverse and additional material regarding risk factors. This enhances the sensitivity and decreases the postoperative neurological deficits.

From our data, we conclude that multimodal IONM is useful in spine surgeries with a sensitivity of 96.6% and specificity of 97.4% in the detection of postoperative neurological deficits in spine surgeries. Use of decision algorithm and multimodal neuromonitoring consisting of TcMEPs, SSEPs, and EMG complement each other in the detection of neurological injury during the course the surgery and prevents further damage and morbidity in patients while improving the intraoperative care.

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Notes

Author Contributions

All of the authors declare that they have all participated in the design, execution, and analysis of the paper, and that they have approved the final version.

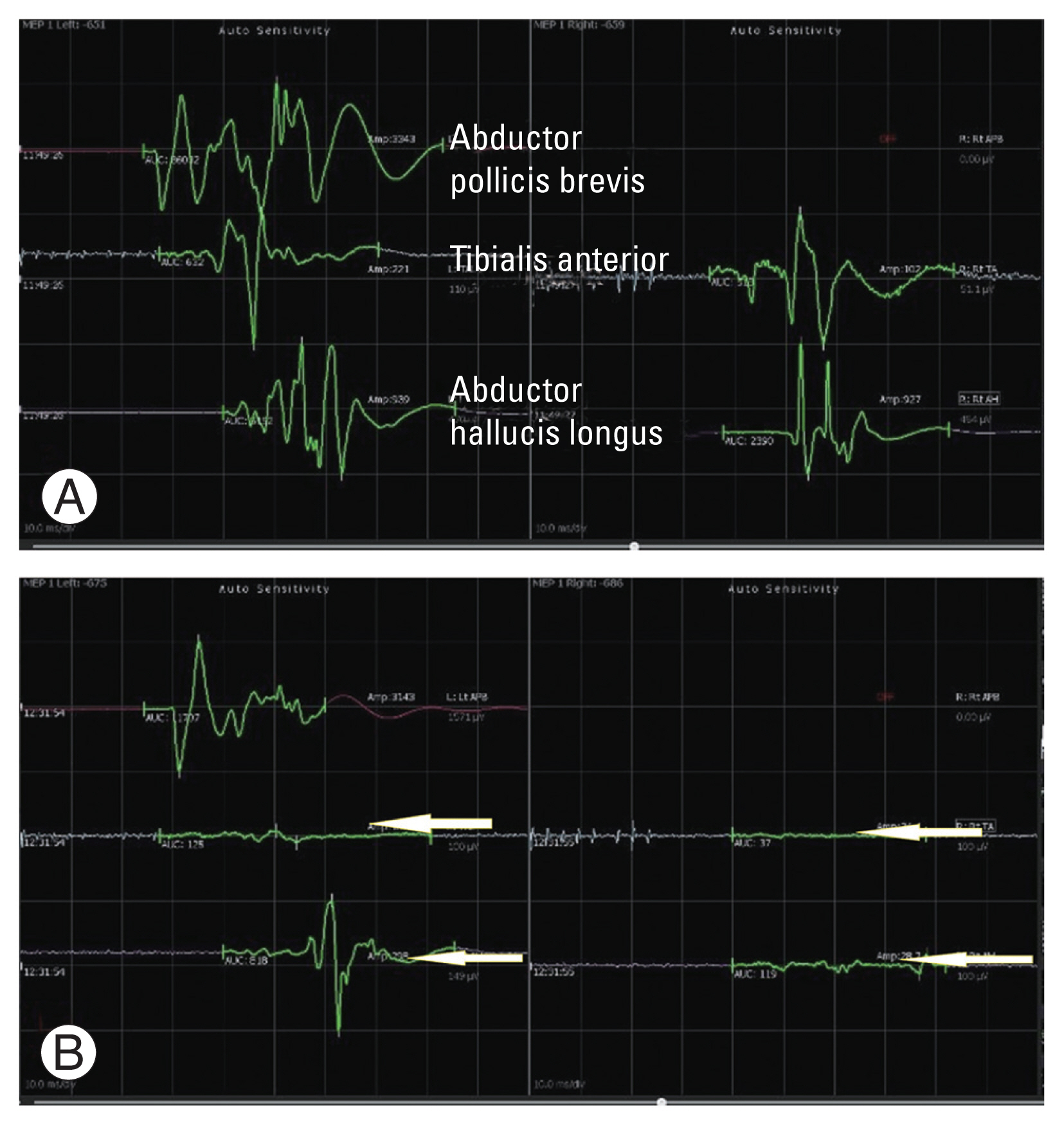

Fig. 2

During a case of C3 to C7 laminectomy and lateral mass fusion, (A) a significant fall in the TcMEPs (arrows) during the surgery was noticed, following which wake-up test was performed to confirm the change in TcMEPs. (B) Laminectomy was extended after confirmation of neurological deficit. TcMEPs recovered back to normal amplitude (arrows) and patient developed transient neurological deficit which recovered within 24 hours. TcMEPs, transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials.

Fig. 3

(A, B) A case of intramedullary tumor at the level of D7. A fall in the motor evoked potentials were noticed during the surgery in the tibialis anterior and abductor hallucis longus muscle groups bilaterally (arrows pointing towards the affected waves), which required a halt in the procedure. Paraparesis was observed in the postoperative period.

Table 1

Demographic parameters

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 56.3±25.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 277 |

| Female | 131 |

| Height (cm) | 161.9±9.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.8±14.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5±5.4 |

Table 2

Types of operative procedures

Table 3

Summary of patients with change in evoked potentials and postoperative neurological deficits

M, male; F, female; IMSCT, intramedullary spinal cord tumor; TcMEPs, transcranial electrical motor evoked potentials; IDEMSCT, intradural extramedullary spinal cord tumor; SSEPs, somatosensory evoked potentials; AAD, atlantoaxial dislocation; TLIF, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion; CMAP, compound muscle action potentials; MEPs, motor evoked potentials.

Table 4

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgeries

Table 5

Operative procedures and diagnostic values of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring

References

1. Fehlings MG, Kato S, Lenke LG, et al. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative neurologic decline after complex adult spinal deformity surgery: results of the Scoli-RISK-1 study. Spine J 2018;18:1733–40.

2. Pajewski TN, Arlet V, Phillips LH. Current approach on spinal cord monitoring: the point of view of the neurologist, the anesthesiologist and the spine surgeon. Eur Spine J 2007;16(Suppl 2): S115–29.

3. Nash CL Jr, Lorig RA, Schatzinger LA, Brown RH. Spinal cord monitoring during operative treatment of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;(126): 100–5.

4. Khan MH, Smith PN, Balzer JR, et al. Intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring during cervical spine corpectomy surgery: experience with 508 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E105–13.

5. Merton PA, Morton HB. Stimulation of the cerebral cortex in the intact human subject. Nature 1980;285:227.

6. Burke D, Hicks R, Stephen J, Woodforth I, Crawford M. Assessment of corticospinal and somatosensory conduction simultaneously during scoliosis surgery. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1992;85:388–96.

7. Legatt AD. Current practice of motor evoked potential monitoring: results of a survey. J Clin Neurophysiol 2002;19:454–60.

8. Kundnani VK, Zhu L, Tak H, Wong H. Multimodal intraoperative neuromonitoring in corrective surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: evaluation of 354 consecutive cases. Indian J Orthop 2010;44:64–72.

9. Deutsch H, Arginteanu M, Manhart K, et al. Somatosensory evoked potential monitoring in anterior thoracic vertebrectomy. J Neurosurg 2000;92(2 Suppl): 155–61.

10. Hilibrand AS, Schwartz DM, Sethuraman V, Vaccaro AR, Albert TJ. Comparison of transcranial electric motor and somatosensory evoked potential monitoring during cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1248–53.

11. Weinzierl MR, Reinacher P, Gilsbach JM, Rohde V. Combined motor and somatosensory evoked potentials for intraoperative monitoring: intra- and postoperative data in a series of 69 operations. Neurosurg Rev 2007;30:109–16.

12. Lall RR, Lall RR, Hauptman JS, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgery: indications, efficacy, and role of the preoperative checklist. Neurosurg Focus 2012;33:E10.

13. Modi HN, Suh SW, Yang JH, Yoon JY. False-negative transcranial motor-evoked potentials during scoliosis surgery causing paralysis: a case report with literature review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E896–900.

14. Chang SH, Park YG, Kim DH, Yoon SY. Monitoring of motor and somatosensory evoked potentials during spine surgery: intraoperative changes and postoperative outcomes. Ann Rehabil Med 2016;40:470–80.

15. Bhagat S, Durst A, Grover H, et al. An evaluation of multimodal spinal cord monitoring in scoliosis surgery: a single centre experience of 354 operations. Eur Spine J 2015;24:1399–407.

16. Zhuang Q, Wang S, Zhang J, et al. How to make the best use of intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring?: experience in 1162 consecutive spinal deformity surgical procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1425–32.

17. Garces-Ambrossi GL, McGirt MJ, Mehta VA, et al. Factors associated with progression-free survival and long-term neurological outcome after resection of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: analysis of 101 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;11:591–9.

18. Sala F, Palandri G, Basso E, et al. Motor evoked potential monitoring improves outcome after surgery for intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a historical control study. Neurosurgery 2006;58:1129–43.

19. Pelosi L, Lamb J, Grevitt M, Mehdian SM, Webb JK, Blumhardt LD. Combined monitoring of motor and somatosensory evoked potentials in orthopaedic spinal surgery. Clin Neurophysiol 2002;113:1082–91.

20. Langeloo DD, Lelivelt A, Louis Journee H, Slappendel R, de Kleuver M. Transcranial electrical motor-evoked potential monitoring during surgery for spinal deformity: a study of 145 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:1043–50.

21. Park P, Wang AC, Sangala JR, et al. Impact of multimodal intraoperative monitoring during correction of symptomatic cervical or cervicothoracic kyphosis. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;14:99–105.

22. Lee JY, Hilibrand AS, Lim MR, et al. Characterization of neurophysiologic alerts during anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1916–22.

23. Sutter M, Eggspuehler A, Grob D, et al. The validity of multimodal intraoperative monitoring (MIOM) in surgery of 109 spine and spinal cord tumors. Eur Spine J 2007;16(Suppl 2): S197–208.

24. Chen Z. The effects of isoflurane and propofol on intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spinal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput 2004;18:303–8.

-

METRICS

- Related articles in ASJ

-

Patient Positioning in Spine Surgery: What Spine Surgeons Should Know?2023 August;17(4)