Early Detection and Analysis of Children with Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis of the Spine

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

Retrospective case series.

Purpose

The aim of the study is to report the clinical characteristics, early diagnosis, management, and outcome of children with multidrug-resistant (MDR) tubercular spondylodiscitis and to assess the early detection of rifampicin resistance using the Xpert MTB/ RIF assay.

Overview of Literature

MDR tuberculosis is on the rise, especially in developing countries. The incidence rate of MDR has been reported as 8.9% in children.

Methods

A retrospective study of children aged <15 years of age who were diagnosed and treated for MDR tuberculosis of the spine was conducted. Confirmed cases of MDR tuberculosis and patients who had completed at least 18 months of second-line antituberculous treatment (ATT) were included. Children were treated with ATT for 24 months according to drug-susceptibility-test results. Outcome measures included both clinical and radiological measures. Clinical measures included pain, neurological status, and return to school. Radiological measures included kyphosis correction and healing status.

Results

Six children with a mean age of 10 years were enrolled. The mean follow-up period was 12 months. All the children had previous history of treatment with first-line ATT, with an average of 13.6 months before presentation. Clinically, 50% (3/6 children) had psoas abscesses and 50% had spinal deformities. Radiologically, 50% (three of six children) had multicentric involvement. Three children underwent surgical decompression; two needed posterior stabilization with pedicle screws posteriorly followed by anterior column reconstruction. Early diagnosis of MDR was achieved in 83.3% (five of six children) with Xpert MTB/RIF assay. A total of 83.3% of the children were cured of the disease.

Conclusions

Xpert MTB/RIF assay confers the advantage of early detection, with initiation of MDR drugs within an average of 10.5 days from presentation. The cost of second-line ATT drugs was 30 times higher than that of first-line ATT.

Introduction

The incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis shows an alarming increasing trend. the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 1 million children were infected by tuberculosis and 140,000 children died from the disease in 2014 [1]. India ranks first as a “high-burden country” among the 22 countries noted by WHO in terms of cases of tuberculosis and MDR tuberculosis. Among the total 1,609,547 people infected with tuberculosis in the year 2014, India reported 95,709 cases in children. Seddon et al. [2] has reported an incidence of 8.9% of MDR tuberculosis in children at Cape Town, South Africa. Multidrug resistance is defined as resistance to at least Isoniazid and Rifampicin among the first-line antituberculous drugs [3]. Tubercular spondylodiscitis especially in children under the age of 10 years, if delayed in diagnosis or inappropriately treated, can lead to debilitating neurological deficits and severe deformity leading to permanent disability [4,5]. There are few publications in the literature regarding MDR tuberculosis of the spine in children [6-8]. In this study, we report the early diagnosis, management, and outcome of children affected with MDR tubercular spondylodiscitis.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted from 2006 to 2014 on all children aged <15 years treated for proven tubercular spondylodiscitis at our center. The study was conducted after getting appropriate consent from the parents of the children. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was made on the basis of growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on mycobacteria growth indicator tube culture or Lowenstein–Jensen culture medium, or on positive detection of nucleic acids by the Xpert MTB/RIF assay from a biopsy or aspirate from the spinal lesion. Children who had completed at least 18 months of their second-line antituberculous treatment (ATT) were included in the study.

Demographic characteristics, prior history of tuberculosis, history of contact with tuberculosis, and details of their antituberculous therapy were noted. Clinically, an assessment of pain by a visual analog scale [9], deformity (measured using Konstam’s angle by Konstam and Blesovsky [10]), and neurological status of the patient (assessed by the American Spinal Injury Association [ASIA] Impairment Scale [11]) were noted. Markers of inflammation, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and liver function tests were also documented. Radiological evaluation by plain radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the affected region was performed before and after completion of treatment.

1. Surgical care

The indications for surgery included the following: ‘spine at risk’ signs [12], destruction of the vertebral body leading to significant mechanical instability, neurological deficit (according to ASIA Impairment Scale classifications A, B, and C), and presence of deformity of >40° [13]. Drainage procedures, such as costotransversectomy and anterolateral decompression, were performed for children who did not have mechanical instability. In those children with severe pain and instability, stabilization of the spine was performed after decompression of the cord. Debridement of the granulation tissue, followed by anterior column reconstruction using a cage filled with autogenous cancellous bone graft was performed by the extended posterior circumferential decompression (EPCD) approach [14].

2. Antituberculous chemotherapy

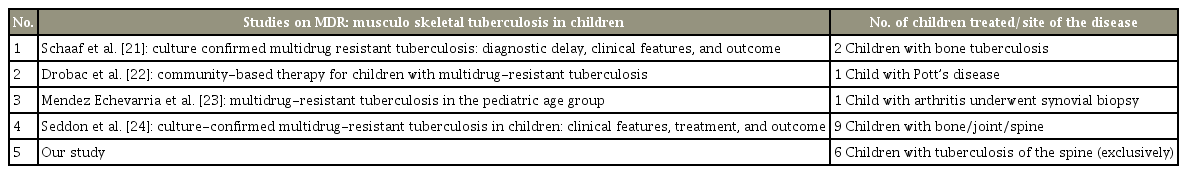

Once the diagnosis was confirmed to be drug-resistant tuberculosis by culture sensitivity or by the presence of rifampicin resistance in the Xpert MTB/RIF assay, patients were started on second-line antituberculous chemotherapy. All the children were treated with multiple antituberculous drugs for a period of 24 months as per drugsusceptibility tests and following guidelines recommended for pulmonary drug-resistant tuberculosis by Seddon et al. [15] and Schaff and Marais [16]. The various drugs used are shown in Table 1. The intensive phase included an injectable second-line drug for a period of 6–9 months, and the continuation phase included only oral drugs, which were administered for a period of 15–18 months. Drugrelated complications and the cost of medications per patient were also considered. Thyroid function tests, audiometry, and liver and renal function tests were performed regularly to reveal possible drug-related adverse effects.

The patients were followed up every 2 months for the first 6 months. Then they were followed up quarterly for the first year, half yearly until completion of therapy, and yearly thereafter.

3. Outcome analysis

Healing was assessed by clinical, biochemical, and radiological criteria. Reductions in pain, healing of sinuses, and return to school were the clinical parameters assessed. Markers of inflammation, such as ESR and CRP, were measured to assess healing. Presence of remineralization and reappearance of bony trabeculae, sharpening of articular margin, sharpening of cortical margin, sclerosis of vertebral body and end plates, and presence of sentinel sign [17] on plain radiographs were considered as radiological signs of healing. On MRI, the criteria for healing included a complete absence of paravertebral collection, complete resolution of enhancement of the vertebra, and fatty replacement of marrow [6].

Results

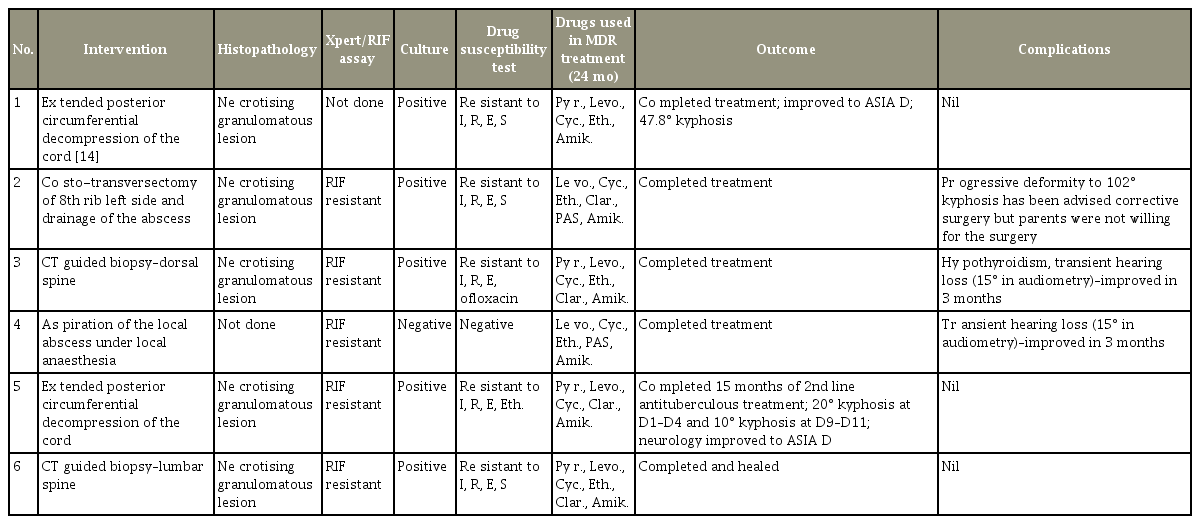

A total of six children (four boys and two girls) with a mean age of 10 years were treated for MDR tubercular spondylodiscitis during this 7-year period. All the children had proven MDR tuberculosis either by culture or by Xpert MTB/RIF assay. Average follow-up of these children after the completion of treatment was 12 months. Their demographic data, clinical presentation, and level of involvement are shown in Table 2. The investigations, interventions, drug-susceptibility-test results, antituberculous chemotherapy, and the children’s outcome is described in detail (Table 3).

Demography, clinical presentation and level of involvement in children with tuberculous spondylodiscitis

Four of the six children were from West Bengal and the other two were from Northeast India. All the patients were negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). All the children had a previous history of treatment with first-line ATT, with an average period of 13.6 months before presentation. Clinically, 50% (three of six children) had psoas abscess and 50% had spinal deformity. Radiologically, 50% (three of six children) had multicentric involvement and the rest (three of six children) had involvement of >3–4 vertebrae, including their intervening discs.

Surgery was indicated in only three of the six children (50%). One child underwent costotransversectomy for decompression, and the remaining two children underwent surgery for significant deformity and neurological deficit (ASIA B paraplegia with only intact perianal sensation). They underwent debridement of the granulation tissue, drainage of the abscess, circumferential decompression of the cord, and stabilization with pedicle screws by the EPCD approach; they gradually improved to ASIA D over a period of 4–6 months.

1. Role of Xpert MTB/RIF assay

In our center, Xpert MTB/RIF assay was available only from the year 2012. The average time from the time of presentation (to the hospital) to the initiation of appropriate second-line antituberculous chemotherapy varied. For the child for whom an Xpert MTB/RIF assay could not be performed (because of the unavailability of the assay in 2009), second-line ATT was started 105 days after presentation. For the other five children who underwent the Xpert MTB/RIF assay, the time to nitiate second-line ATT was on average 10.5 days.

2. Outcome

Five of the six children (83.3%) completed treatment and were cured of the disease. One child is still being treated. Two children had developed transient hearing loss, which gradually improved over 2–3 months; and one child had developed hypothyroidism, which was treated with oral thyroxine supplementation.

The calculated cost of medications per child showed that the cost for children who were treated with first-line chemotherapy for a period of 9 months was an average Rs. 3,338 ($48) and the cost of medicines for the children who were treated with second-line chemotherapy for MDR for a period of 2 years was an average Rs. 82,410 ($1,200).

3. Illustration

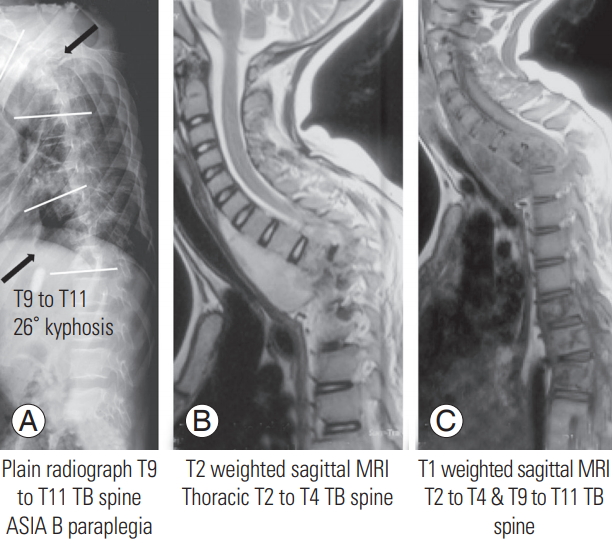

A 12-year-old girl presented with mid-back pain for 9 months and weakness of her legs for 20 days. She had a previous history of treatment with ATT 3 years previously for a sternal swelling. She had ASIA B paraplegia, with a deformity of 57° kyphosis at T1–T4 and 26° kyphosis at T9–T11 (Fig. 1). She underwent drainage of the abscess, circumferential decompression of the cord, and deformity correction using the EPCD approach. Her Xpert MTB/RIF assay showed rifampicin resistance, and she was started on MDR drugs according to drug susceptibility test results. Postoperatively, the deformity was corrected to 20° and 10° kyphosis at T1–T4 and T9–T11 spine, respectively (Fig. 2); her neurology improved gradually to ASIA D, and she was able to walk independently with the aid of bilateral axillary crutches.

(A) Plain radiograph lateral view of the spine showing involvement of the T1–T4 and T9–T11 spine with 57° and 26° of kyphosis, respectively. (B) T2 weighted sagittal MRI showing significant prevertebral abscess extending up to the T4 vertebra and significant cord compression at T2–T4. (C) T1 weighted sagittal MRI demonstrating involvement of T9–T11 vertebrae with pathological subluxation of the vertebra. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association.

(A) Immediate postoperative plain radiograph lateral view showing with pedicle screws and fusion with anterior cage and cancellous bone graft. (B) Two-year follow-up plain radiograph lateral view with significant improvement in kyphosis angle of 20° and 10° at T1–T4 and T9–T11 spine, respectively. (C) T2-weighted sagittal MRI image at 2-year follow-up with near-total resolution of the prevertebral and epidural abscess. MRI, magnetic reso- MRI, magnetic reso magnetic resonance imaging; ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association.

Discussion

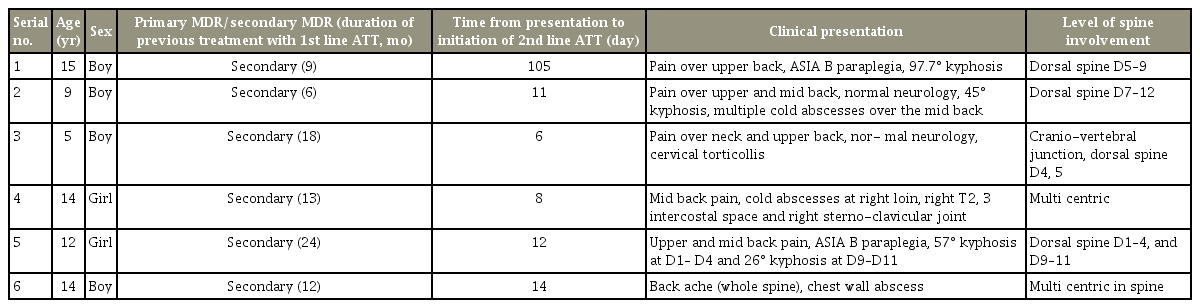

Childhood tuberculosis is alarmingly on the rise. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis accounts for almost 20%–30% of all childhood tuberculosis. The common reasons for inaccurate estimates of the disease burden globally are the paucibacillary nature of the disease, the unavailability of resources in some countries for investigation, and finally, inadequate reporting and recording of the disease [18]. MDR tuberculosis in children is a globally emerging disease. The cause of multidrug resistance is multifactorial. The main cause of MDR tuberculosis in children is transmission from an adult with drug-resistant tuberculosis rather than from previous treatment with antituberculous drugs [16]. Early detection of the disease and prompt management of tuberculosis of the spine significantly decreases devastating neurological complications and permanent disability [19]. Early diagnosis and effective treatment are the most effective tools [20]. Few studies have been published in the literature on children with MDR tuberculosis of the skeletal system [21-24] (Table 4).

A young age (<5 years), HIV infection, a previous history of treatment for TB, contact with an adult with drugresistant tuberculosis, and source case being an alcoholic were identified as risk factors [25]. In our study, patients were young, with a mean age of 10 years, none of who were aged >5 years of age, none were positive for HIV, and all (100%) had previously been treated with first-line ATT for a mean period of 13.6 months.

According to Schaff and Marais [16], a common cause of MDR tuberculosis is delayed diagnosis. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is paucibacillary in nature, and mycobacterial culture is a weak gold standard for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis [26]. The WHO had recommended the use of Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Xpert; Cepheid, Sunnydale, CA, USA) [27] for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. In 2013, the WHO extended the use of Xpert MTB/RIF for extrapulmonary tuberculosis as a replacement test for other nonrespiratory specimens (conditional recommendation) with low-quality evidence. The dual advantage of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay is its rapid detection of tuberculosis and its ability to detect rifampicin resistance. Xpert MTB/RIF, being a molecular assay, detects up to 131 cfu/mL [28]. Xpert offers better sensitivity for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children [29]. The Xpert MTB/RIF assay showed a sensitivity of 95.6% and a specificity of 96.2% for patients with tubercular spondylodiscitis [30]. Our study revealed that the average time from presentation to initiation of MDR treatment was 105 days (15 weeks) for the child for whom the Xpert MTB/RIF assay could not be performed and 10.5 days for the children who had early diagnosis using the Xpert MTB/RIF assay. Emphasis is on early and rapid detection of the disease with the Xpert MTB/RIF assay and to begin appropriate treatment in the early phase of the disease. Early detection and initiation of therapy in children with MDR tuberculosis of the spine should halt advancement of the disease, preventing extensive destruction of vertebral elements.

The WHO protocol for drug resistance has been designed only for pulmonary MDR, and the same guidelines were followed for tubercular spondylodiscitis. Seddon et al. [8] have suggested that the guidelines for MDR spinal disease are similar to those of pulmonary tuberculosis. In our study, 83% (five of six) of the children were cured of the disease, which is similar to the meta-analysis that reported a pooled estimated treatment success rate of 81.67% [31]. Globally, only 50% of the children with MDR tuberculosis were successfully treated as per the latest report in 2015 [1].

The cost per child for medicines treating MDR revealed a 25–30-fold increase when compared with that of conventional first-line antituberculous chemotherapy. The WHO analysis in 2014 showed a 50- to 60-fold increase in the cost for treatment of a patient with multidrug resistance [1]. However, they did not differentiate adults and children, and likely included both adults and children. In developing countries, the cost factor plays a major role in patient compliance. The cost analysis excludes the cost of surgery, surgical implants, hospital consultations, investigations, drug-related complications, cost of stay, and travel expenditure.

Conclusions

The Xpert MTB/RIF assay aids in the initiation of secondline ATT at an average 10.5 days from presentation. The cost of drugs for treating children with MDR tubercular spondylodiscitis was 30 times more than that of first-line ATT for conventional tuberculosis. Although the drugs used for MDR treatment were costly, there were few drugrelated complications, the children generally tolerated them well, and were cured of the disease.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Authors’ contribution

Arockiaraj J: design, analysis, interpretation of data, and draft manuscript; Robert M: analysis, interpretation of data, and draft manuscript; Rose W: analysis, correction, critical revision, and final approval; Amritanand R: correction, critical revision, and final approval of the draft; David SK: correction, critical revision, and final approval of the draft; and Krishnan V: correction, critical revision, supervision, and final approval.