Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Objective Measurement Scales and Ambulatory Status

Article information

Abstract

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is one of the most common affecting the elderly population that may lead to loss of function and the inability to execute basic activities of daily living. While surgical decompression remains the standard of care, choosing an optimal management strategy is usually guided by a set of clinical, radiological, and measurement indices. However, to date, there is a major uncertainty and discrepancy regarding the methodology used. There is also inconsistent adoption of outcome measures across studies, which may result in huge limitations in predicting the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of different treatment paradigms. Herein, we review the various measurement indices used for outcome assessment among patients with LSS, and delineate the major advantages and disadvantages of each index. We call for the development of a single objective outcome measure that encompasses and addresses all issues encountered in this heterogeneous group of patients, including monitoring the patient’s progression after treatment.

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a frequently encountered condition in elderly patients (age >65 years) [1]. Neurogenic claudication in elderly patients may cause loss of function and an associated inability to perform basic activities of daily living. Elderly patients demand medical care, including surgery, not only to save their lives but also to increase its quality. Most patients are managed nonoperatively; however, a subset of patients with refractory symptoms requires surgical decompression of neural elements [2-4].

Various treatment modalities with variable success rates have been used to manage LSS. To date, surgical decompression with laminectomy remains the gold standard treatment modality. However, choosing the optimal management strategy is usually guided by a set of clinical, radiological, and measurement indices. Currently, there is a major uncertainty and discrepancy in the methodology used, as well as inconsistent adoption of outcome measures across studies [5-7]. Various scales that assess symptom severity and functional disability have been established to evaluate treatment effictiveness as well as patients' pre- and post-treatment stauts. Such variations can impose huge limitations in predicting the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of different treatment paradigms. Therefore, having an optimal measurement index that correctly predicts treatment efficacy would significantly improve patient selection and outcomes.

Here, we review the various measurement indices used for outcome assessment in patients with LSS and delineate the major advantages and disadvantages of each index.

Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire

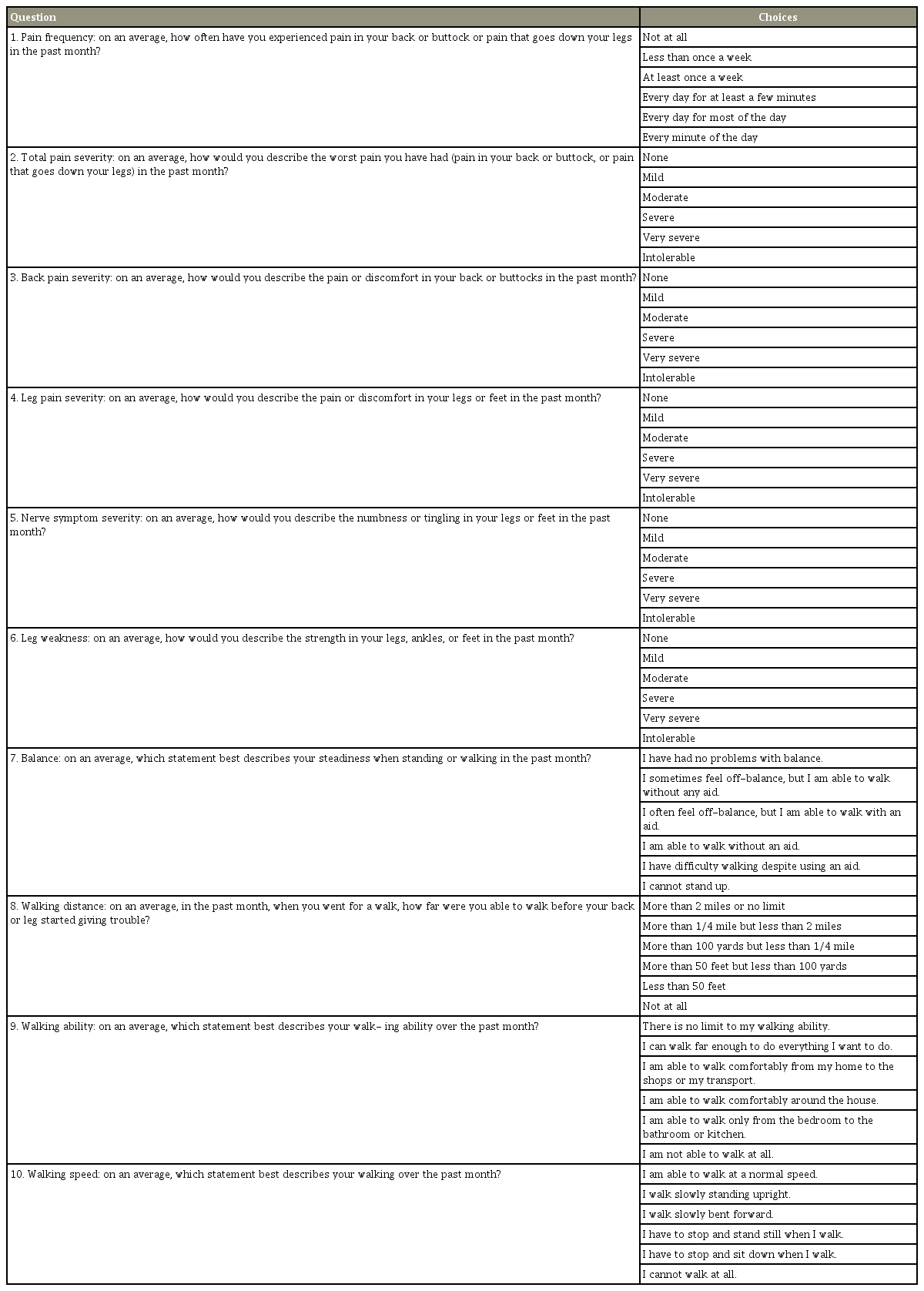

The Swiss Spinal Stenosis (SSS) Questionnaire, also known as the “Swiss Spinal Stenosis measure,” the “Brigham Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire,” and the “Zurich Claudication Questionnaire” is specific to LSS and is used to supplement existing measures of disability and health status [8]. Studies have demonstrated its accuracy and reliability in measuring neurogenic claudication and walking capacity in patients with LSS [9,10]. The questionnaire was developed by Stucki et al. [8] in 1995 to address the symptoms and physical activity limitations within the prior month. It encompasses twelve questions related to two components: the first scale is for the assessment of symptom severity, whereas the second scale is for the assessment of functional disability caused by spinal stenosis [8].

The first scale (symptom severity) includes seven questions related to back and lower limb symptoms (pain, numbness, and weakness) and balance. The questions are divided into two domains: the pain (questions 1–4) and the neuroischemic domain (questions 5–7). Except for the question related to balance, each of the six questions are scored from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating the absence of symptom and 5 indicating very severe occurrences of symptom. The seventh question is related to balance and includes only three options scored as 1, 3, or 5 [8].

The second scale (functional disability) includes five questions (8–12) that primarily assess walking capacity. Each question is scored from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater disability. Scores are calculated from each scale to provide an overall score, taking into consideration that no more than two responses should be missing. The extent of patient satisfaction after treatment can be measured using a third scale (six questions), which is not part of the primary questionnaire [8].

Various studies have shown that the SSS Questionnaire is a valid, reliable, and responsive tool for patients with LSS [8,11-14]. Unlike other scales, the SSS Scale is specific to LSS and has been identified as the “best and most specific outcome measure for spinal stenosis” by the North American Spine Society guidelines for LSS [15].

Owing to its specificity, validity, and reliability, the SSS Questionnaire has been used in various studies and clinical trials. In addition, the scale focuses on neuroischemic symptoms, which are frequently encountered in patients with LSS. These types of questions are not present in most other scales. However, the scale has some limitations. Using Rasch analysis, the symptom severity scale fails to function as a unidimensional domain [16]. Making the scale unidimensional would require the deletion of questions three and six, thereby leading to a reduction in its reliability and power. Therefore, it is recommended to subdivide the first scale (symptom severity scale) into two separate subscales, which would address the general pain (questions 1–3) and neuroischemic symptoms (questions 4–7) [11,16]. Conversely, the physical disability scale performs as a unidimensional scale in Rasch analysis. However, question 11 is not clinically significant, and the physical disability scale would be appropriate for statistical analysis using the Rasch analysis model by excluding it [16].

Quebec Back Pain Disability Questionnaire

The Quebec Back Pain Disability Questionnaire is a tool for measuring the pain and disability caused by back pain [17]. In the questionnaire, patients rate their difficulty with a set of tasks and activities. Patients rate each of the 20 activities on a scale from 0 (not difficult at all) to 5 (unable to perform). The overall score is calculated from the sum of individual scores from all 20 items, with a higher score indicating greater back pain and disability [17].

Pain Disability Index

Pain Disability Index comprises seven questions used to measure the patient’s perceived level of disability across different daily activities, such as self-care, family responsibilities, and social activities. Scoring is done using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS), in which each of the seven questions is rated based on the severity of disability from 0 to 10 with a possible total score of 70. A higher score indicates more severe pain-related disability. The index's construct validity and reliability have been proven using psychometric analysis [18].

Oswestry Disability Index

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was developed by John O’Brien in 1976 is another tool to assess back pain-related disability [19]. It encompasses nine questions related to activities of daily living, such as walking and personal care, rated on Likert scales of 5 or 6 points. The score is calculated as a percentage of the total possible score of 53, with a greater score indicating greater back-related disability [19,20]. The ODI is one of the most commonly employed tools used by surgeons and is utilized in a large number of studies in the literature. Owing to its wide and common use, the ODI is a valid and reproducible instrument of back pain-related disability and has been used to evaluate walking in patients with LSS [21,22]. The ODI has been analyzed using the Rasch method [23,24].

There are four versions of the ODI, each having its own criteria [5,18,25-32]. Some versions contain questions related to sexual life and performance, which may not be acceptable in some cultures [33-36]. One of its major advantages is that it can be easily translated, and except for few questions, can be implemented in several cultures. The ODI has been translated into Danish, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Spanish, Swedish, and other languages [36-42].

The ODI is the preferred outcome metric for patients with severe symptoms. However, this preference may lead to a selection bias and incorrect reporting of outcomes [43]. Another issue related to the ODI is the time scale. ODI questions are developed to elicit a response about functioning “at the moment” the questions are asked. However, it is well known that symptom variation from one day to another is common among patients with LSS; thus, such specifications of time may overlook active issues the patient previously had but not currently experiencing when completing the questionnaire. This aspect affects the reliability of the test [12,43]. Additionally, the ODI scale does not consider the neuroischemic symptoms encountered by patients with LSS, thereby making its utility in patients experiencing such symptoms limited [43]. Conversely, the ODI scale has been shown to correlate most closely with the degree of patients' satisfaction after surgery for LSS [44].

Short-Form Health Survey

The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is an instrument developed to assess the overall health and disability among patients with LSS [45]. It comprises 36 items, with each question categorized into one of the following scales: general health, physical functioning, social functioning, role limitation (physical limitation, role limitation), emotional, mental health, energy/fatigue, pain, and comparative health. A score from each scale is calculated independently using algorithms defined by the authors [45]. Generally, each scale is directly transformed into a 0–100 scale, with a lower score indicating more disability and a higher score indicating less disability. The SF-36 has been analyzed using the Rasch method [46-48]. SF-36 is widely used for the estimation of cost-effectiveness of treatments in health economics and constitutes a variable when calculating the quality-adjusted life year. Recently, a shorter version of the SF-36 was published with a reduction of the number of items from 36 to 12, for those interested in the physical and mental domains of the survey.

Self-Paced Walking Test & Shuttle Walk Test

Self-Paced Walking Test (SPWT) assesses walking capacity by measuring the total distance the patient can continuously walk on a flat surface at a self-selected pace, until experiencing symptoms of LSS or reaching a limit of 30 minutes [49]. SPWT has demonstrated high retest reliability in patients with LSS [49]. As with other questionnaires that evaluate walking in patients with LSS, SPWT is mostly associated with measuring the capacity and not performance. The information gained from these questionnaires may provide an incomplete, and possibly misleading, estimate of a patient’s level of disability. Therefore, adding daily activity monitors for a certain time may be advantageous, as it allows for measurement of both capacity and performance [50]. The objective nature of the SPWT is a major advantage because it eliminates any subjective bias like that observed with other outcome measures.

Shuttle Walk Test (SWT) is a ten-meter course performed on a flat surface without any obstacles. The patient listens to a tape recorder explaining the test prior to starting and is asked to walk ten meters within a specified time. The assessor counts the number of shuttles (laps) and maximum distance. The result of the test is given in meters (number of completed shuttles multiplied by 10) [51-53]. The advantage of this test is its simplicity, both in understandability as well as the minimal equipment involved. In one study, the authors reported that a change of 76 m would be required in SWT for 95% certainty that the change was not a chance occurrence [12]. Therefore, using SWT to monitor the progression of symptoms among patients with LSS may be useful.

Visual Analog Scale

VAS is a psychometric response scale for subjective characteristics or attitudes that cannot be directly measured [54,55]. It is a commonly used to evaluate pain in patients with LSS. The patients rate their level of pain by indicating a position along a continuous line between two endpoints, wherein one end indicates “no pain” and the other indicates “worst possible pain.” VAS has been shown to be a very sensitive and reproducible test [56]. However, it remains a subjective measurement index and lacks specificity to LSS. Several studies have used VAS assessing pain related to various other etiologies [55,57]. Yet, VAS is still commonly used among surgeons dealing with LSS patients to estimate the severity of pain and intervene accordingly. A numerical system may be used with VAS, wherein 1 would indicate “no pain” and 10 would indicate “worst possible pain.”

Japanese Orthopedic Association

Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score was developed in 1976 to measure the functional status among patients with cervical myelopathy [58]. It was revised in 1994 to include assessment of shoulder and elbow functions [59]. The use of both scales has been reported in the literature, and they are considered the most frequently used scales in patients with cervical myelopathy. Despite its use in cervical myelopathy, the use of both scales has also been reported in a great number of studies in patients with LSS. The JOA scale comprises six domains, with each scored differently (Table 1) [58,60].

The scale was developed in Japan and was designed primarily for the Japanese population. Thus, one of the major limitations of this scale is that it evaluates motor dysfunction by assessing a patient’s ability to use chopsticks. The use of chopsticks is limited to East Asian cultures, including the Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Vietnamese populations. Therefore, using this parameter to evaluate motor ability may not be applicable in the other parts of the world. This limitation of cultural differences in eating habits has already been addressed in previous reports [61,62].

Like the ODI scale, the JOA score has been modified with three different versions reported in the literature, each with different scales and scoring systems [63-65]. Therefore, the potential of data misinterpretation and confusion across these different versions is not uncommon. The reliability of both JOA and modified JOA (mJOA) has been reported to be high [60,66]. However, the test-retest reliability of the mJOA has not yet been reported.

Out of the three modified versions, the most widely-used mJOA score is the one developed by Benzel et al. [63] in 1991. The scale comprises four domains, each scored differently (Table 2) [63]. One of the advantages of this scale is that it omits the question related to the use of chopsticks and replaces it with the use of spoons to evaluate the motor function of the upper limbs, thereby eliminating the issue associated with cultural differences [63].

This modification and others in the mJOA have not yet been validated; however, a recent study demonstrated that the domains and total scores of the JOA and the mJOA are strongly correlated with each other, even though the latter does not include scales for measuring sensory function in the trunk and lower extremities [67]. Yet, the Bland–Altman analysis indicated that these scoring systems are not interchangeable [67]. Finally, although the JOA and mJOA are widely reported in the LSS literature, both scales seem to be more specific for cervical myelopathy rather than LSS.

Euro Quality of Life-5D

Euro Quality of Life-5D (EQ-5D) is composed of a descriptive scale and a VAS [68]. The former covers five domains: mobility, usual activities, self-care, anxiety/depression, and pain/discomfort. Each domain contains three options (no problems, some problems, severe problems). In the VAS, the patient is asked to rate his/her health on a vertical visual scale with options ranging from the “worst imaginable health state” to “best imaginable health state.” The EQ-5D scores for the US population range from −0.11 (worse than death) to 1.0 (full health), with a score of 0 indicating death [69].

One of the major advantages of this scale is that it measures both the economic as well as the clinical status of the patient. Thus, it provides the physician with a good estimate of the patient’s clinical condition and the cost-effectiveness of the treatment modality to be used [68,69]. Moreover, EQ-5D scores correlate well with the widely-used ODI scores [70]. Interestingly, the EQ-5D scales include a domain on “anxiety/depression,” which is not found in other scales and is very important in evaluating patients with LSS both pre- and postoperatively. However, as with other scales, the EQ-5D lacks specificity, as it can be used in several other spinal and non-spinal conditions and diseases. Owing to its lack of specificity, the conditions and environment of questionnaire administration may greatly influence and change the answers of the more generalized health questions, thereby affecting test reproducibility [70].

Oxford Claudication Score

Oxford Claudication Score (OCS) comprises 10 questions covering three domains: pain (questions 1–4), ischemia (questions 5–7), and physical symptoms (questions 8–10) [71]. Each question is scored between 0 and 5, with higher scores correlating with worse disability (Table 3) [71]. The total score is expressed as a percentage of the maximum possible score. Like the SSS, the OCS includes questions related to symptoms experienced in the past month prior to presentation. The major advantage of the OCS is its specificity to LSS, particularly in terms of pain and walking difficulty [12,71].

Conclusions

Each of the various outcome measures reported in the literature for the evaluation of patients with LSS have positive and negative attributes, thereby contributing to the variability in the observed success rates among various surgical and non-surgical interventions. Not a single outcome measure adequately captures all functional domains in patients with symptomatic LSS; therefore, a combination of questionnaires may be necessary to adequately capture the impact of LSS on a patient’s pain, disability, and quality of life. Thus, patients and physicians can potentially benefit from a single objective outcome measure that encompasses and addresses all these issues and can also monitor patients' progression after treatment. Clinicians as well as third party payers can potentially benefit from a more rigid evaluation technique for LSS, thereby better ascertaining a judgment of functional improvement for the growing elderly population.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.