|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 9(6); 2015 > Article |

Abstract

Purpose

To translate and validate the Iranian version of the Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale (CNFDS).

Overview of Literature

Instruments measuring patient-reported outcomes should satisfy certain psychometric properties.

Methods

Ninety-three cases of cervical spondylotic myelopathy were entered into the study and completed the CNFDS pre and postoperatively at the 6 month follow-up. The modified Japanese Orthopedic Association Score was also completed. The internal consistency, test-retest, convergent validity, construct validity (item scale correlation), and responsiveness to change were assessed.

Results

Mean age of the patients was 54.3 years (standard deviation, 8.9). The Cronbach ╬▒ coefficient was satisfactory (╬▒=0.84). Test-retest reliability as assessed by the intraclass correlation coefficient analysis was 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.98). The modified Japanese Orthopedic Association score correlated strongly with the CNFDS score, lending support to its good convergent validity (r=-0.80; p<0.001). Additionally, the correlation of each item with its hypothesized domain on the CNFDS was acceptable, suggesting that the items had a substantial relationship with their own domains. These results also indicate that the instrument was responsive to change (p<0.0001).

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) includes cervical herniated disc (CHD) and cervical spinal stenosis and is a progressive spine disease. It is the most common cause of spinal cord dysfunction. The symptoms of CSM depend on the level(s) of spinal cord involvement and its pattern [123].

A variety of measures are available to evaluate CSM and disability, such as the Neck Disability Index [4], the Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire [5], the Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale (CNFDS) [6], the Neck Pain and Disability Scale [7], the Bournemouth Questionnaire for Neck Pain [8], the Patient-Specific Functional Scale [9], the modified Japanese Orthopedic Association (mJOA) [1011], the JOA Cervical Myelopathy Evaluation Questionnaire [12]. The Nurick score [1314], and the JOA score [15], the Cooper-myelopathy scale [16], the Prolo score [17] and the European-myelopathy score [18]. However, it has been argued that none of these instruments are the gold standard [19].

The CNFDS was designed to assess disability related to neck dysfunction. It is a self-administered questionnaire, originally developed in Denmark [6], and is easily understood by patients [8]. It has been translated into Polish, Turkish, and French [192021] and the entire questionnaire can be completed in <10 minutes [6]. Psychometric studies could help clinicians and researchers worldwide to carry out similar studies and compare the results. The aim of this study was to translate the CNFDS into Persian (Iranian language), validate and use the questionnaire to study health-related outcomes in Iranian patients with CSM.

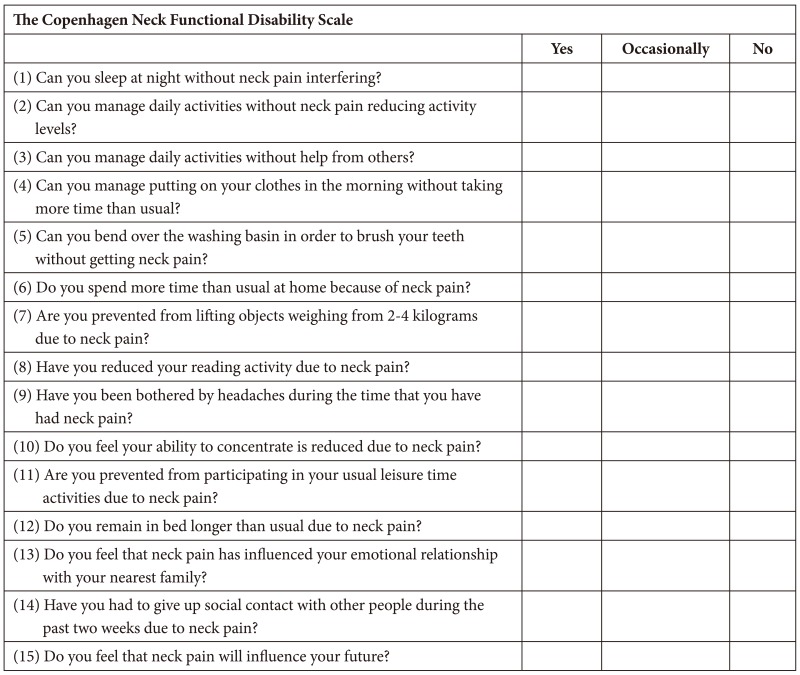

The CNFDS is designed to evaluate the disability experienced by patients with CSM. It consists of three sections including 15 items that evaluate: the impact of neck pain including the patient's perception of the future impact of neck pain (items 1, 5, and 15), disability during everyday activities (items 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 12), and social interactions and recreation (items 6, 9, 11, 13, and 14) [621]. Each item has three possible response categories (yes=0, occasionally=1, and no=2) for the first five items and the remaining items are scored in reverse (yes=2, occasionally=1, and no=0). The total score is 0-30. A higher score indicates greater disability (Appendix 1).

We asked for permission to translate the CNFDS into Persian. Then, the "forward-backward" procedure was applied to translate the CNFDS from English into Persian. Two general practitioners translated the questionnaire into Persian, and these were back translated into English by a health professional and a professional translator. A few changes were made after a careful review, and the provisional Persian version of the questionnaire was pilot tested to establish that it could be understood and that the questions measured what they were intended to measure [222324].

The final draft of the Iranian version was administered to a sample of patients newly diagnosed with CSM who were attending a neurosurgery clinic of a Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Tehran, Iran) during April 2007 to June 2013. No restrictions were put on patient selection with regard to type of CSM, age, or other characteristics. The exclusion criteria were prior cervical spine surgery and spinal anomalies. The stenotic level(s) were localized on magnetic resonance or computed tomography images. All patients had typical symptoms of CSM and were surgical candidates. Two neurosurgical health professionals independently scored the questionnaires of patients admitted for surgery. Both independent observers assessed the patients on the same day. Scoring was performed on the day before surgery. The observers were unaware of the purpose of the study. Patients were assessed pre and postoperatively at the 6 months follow-up.

The key to treating CSM is to remove pressure from the spinal cord. Surgical methods to decompress the spinal cord include three approaches: (1) anterior cervical corpectomy from the front of the neck, as with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion and (2) cervical laminectomy and fusion and cervical laminoplasty from the back of the neck, and (3) combined procedure [25].

In addition to the CNFDS, the Iranian version of the mJOA was administered simultaneously to patients. The mJOA is a self-administered, disease-specific tool that originated from JOA score [1011]. It consists of four sections including 22 items: Motor dysfunction of the upper extremities (six items), motor dysfunction of the lower extremities (eight items), sensation (four items), and sphincter dysfunction (four items). The scores for each section are 0-5, 0-7, 0-3, and 0-3, respectively, giving a total score of 0-18. Higher score indicate less disability. In this study, the total mJOA score was used for the assessment.

The psychometric properties of the CNFDS were evaluated for reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change. (1) Reliability: Cronbach ╬▒ coefficient was used to test reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire, and ╬▒Ōēź0.70 was considered satisfactory. In addition, we assessed test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis. ICC values >0.80 were considered excellent stability [26]. (2) Validity: Construct validity was assessed with the item-scale correlations. Correlations were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient (r) analysis. We expected that item scores would correlate higher with the hypothesized scale than the other scales. Correlation values Ōēź0.40 were considered satisfactory (rŌēź0.81-1.0, excellent; 0.61-0.80, very good; 0.41-0.60, good; 0.21-0.40, fair; and 0-0.20, poor) [19]. In addition the correlation between CNFDS and mJOA scores was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient analysis to assess convergent validity (criterion validity). This type of validity is useful for showing that the construct of an instrument is meaningful. Values Ōēź0.40 were considered satisfactory (rŌēź0.81-1.0, excellent; 0.61-0.80, very good; 0.41-0.60, good; 0.21-0.40, fair; and 0-0.20, poor) [26]. (3) Responsiveness to change: Responsiveness was evaluated as a psychometric property of the questionnaire. As such, the patient's pre and postoperative scores were compared using the paired t-test to examine whether the CNFDS could capture the changes after surgery.

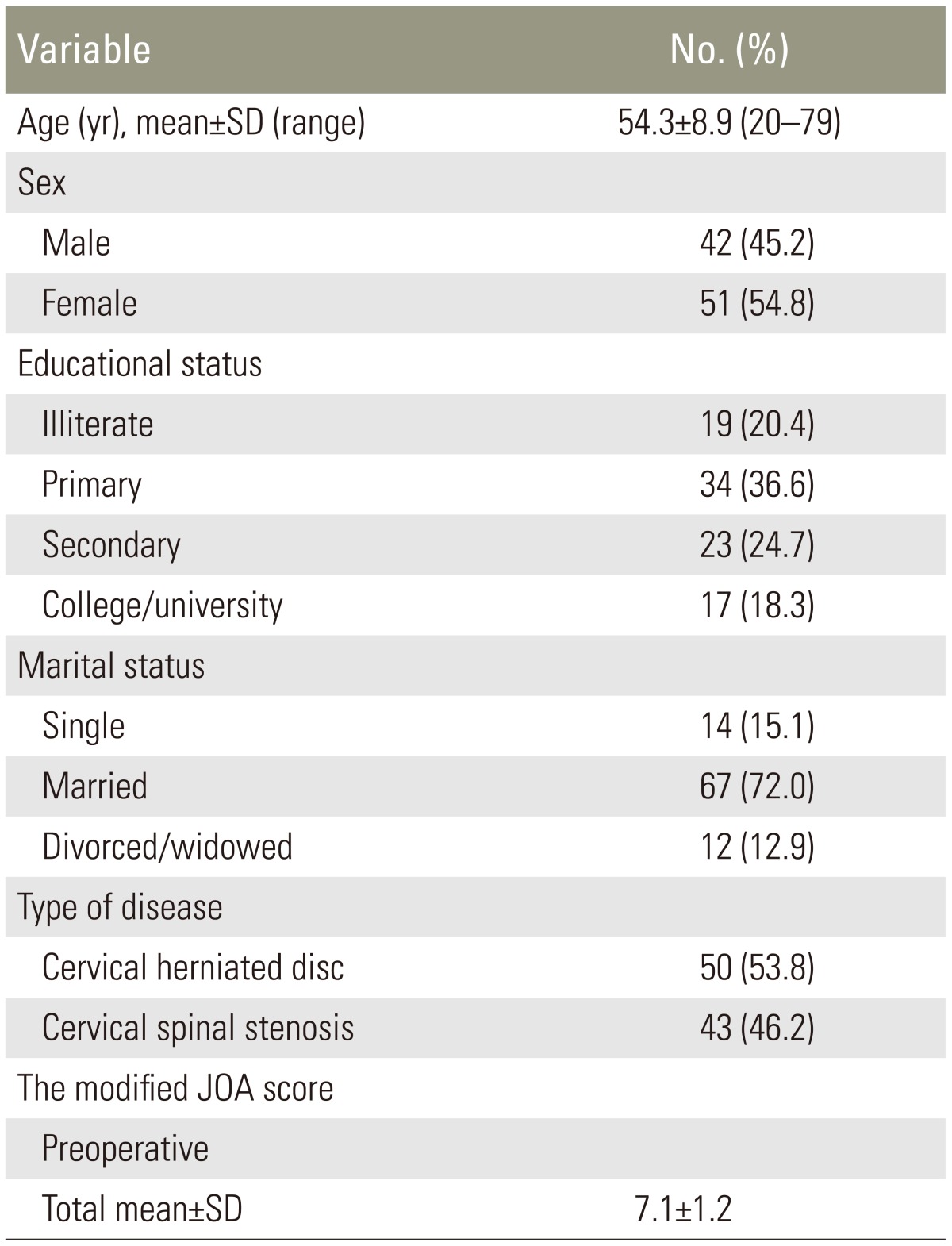

Ninety-three patients with CSM were studied. The mean age of the patients was 54.3 (standard deviation [SD], 8.9) years, most were married (72%), and had completed primary or secondary education (61.3%). The patient's characteristics and their mJOA scores are shown in Table 1. Most patients with CSM had a developmentally narrow spinal canal, and the decompressive laminae were distributed from the C2 to T1 levels. The number of decompressed lamina was 3.1 (SD, 1.0). Most patients with CHD had a one- or two level discectomy distributed from the C2 to C7 levels. Significant differences were observed between the pre and postoperative assessments, indicating improvements on the outcomes and functionality on all subscales (p<0.001). However, no differences were detected between patients with cervical spinal stenosis and CHD (pŌēź0.05).

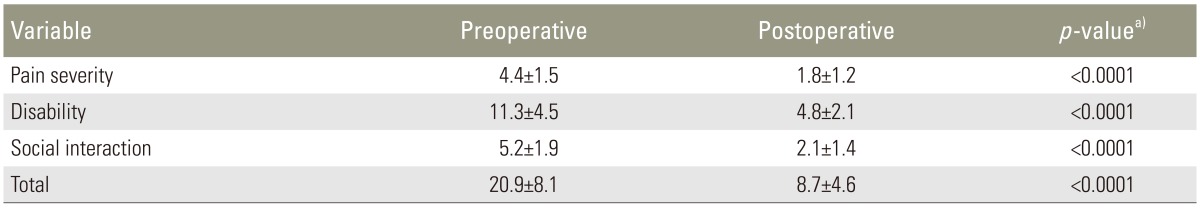

(1) The internal consistency for the CNFDS and its three sections as calculated by the Cronbach ╬▒ coefficient is shown in Table 2. All sections exceeded the minimum reliability standard of 0.70 at the preoperative assessment. The Cronbach ╬▒ for the scale was 0.84, indicating satisfactory results. The results are shown in Table 2. (2) Test-retest reliability: The ICC was excellent (0.95) for the CNFDS (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.98) (Table 3).

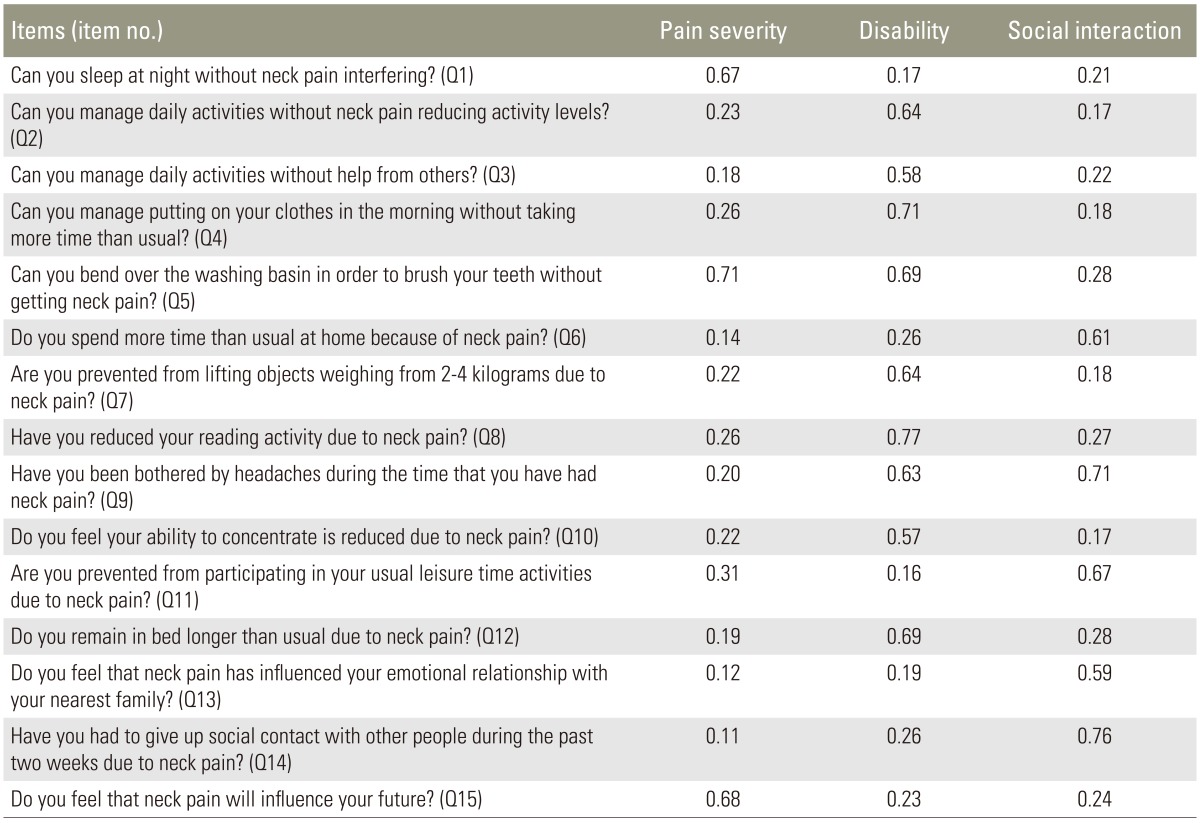

Construct validity of the CNFDS was examined using item-scale correlations and criterion validity. The item scale correlation matrix between each item and the three CNFDS subscales are shown in Table 4. All correlations between items and the hypothesized scale were satisfactory, suggesting that the items had a substantial association with their own subscale. Pearson correlation coefficient exceeded 0.40 (range, 0.57 [Q10]-0.71 [Q4]).

Total score on the CNFDS was correlated strongly with total score on the mJOA, supporting the good convergent validity (r=-0.80, p<0.001).

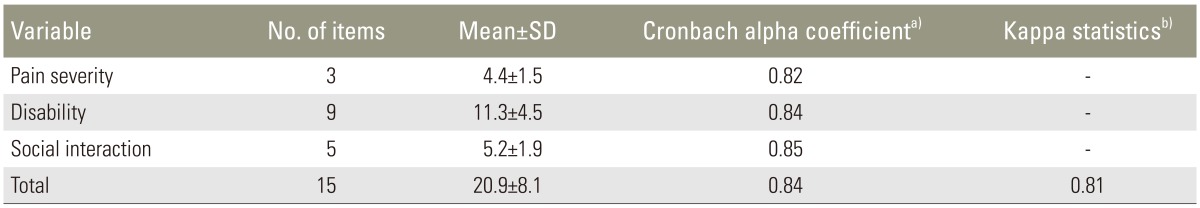

Responsiveness to change was evaluated using the paired t-test. In all instances, the CNFDS detected changes after the intervention (surgery), indicating improvements in all subscales as expected. The outcomes are shown in Table 5.

This study is the first to report on translating and validating an Iranian version of the CNFDS. The results indicate that the Persian version of the CNFDS is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring disability in patients with CSM. The measurements were consistent and reproducible, with good discriminative properties, and was comparable with versions in other languages [6192021].

This Persian version of CNFDS is the only conditionspecific outcome measure for patients with CSM that has undergone a psychometric evaluation in Iran. The Cronbach ╬▒ for the Persian CNFDS exceeded the recommended threshold, suggesting that the Persian version of the questionnaire has satisfactory internal consistency. The results were similar to those reported by other authors who have used this measure in patients with degenerative and discopathic disorders of the cervical spine and chronic neck pain [61921]. Test-retest reliability was examined using ICCs. ICCs of the tool were >0.80, demonstrating good test-retest reliability for the scale, which is similar to other studies reporting psychometric properties of the CNFDS [620]. Our results show that the CNFDS has acceptable interobserver reliability; however, it was not investigated in other studies.

We evaluated convergent validity, which contributes to a psychometric evaluation of the instrument. Correlations between the CNFDS and the visual analog scale [621], or the Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS) have been reported by other studies [62021]. Furthermore, the CNFDS showed excellent item-scale correlation. These results match the good construct validity reported by similar studies in other languages, and could be regarded as a valid measure.

This study had some limitations. Sample size was small, and a larger study would help establish stronger psychometric properties for the questionnaire. We performed a number of limited tests for the validation. It may be necessary to perform other tests, such as a factor analysis, to indicate the factor structure. In addition, we were unable to include other types of neck pain disease in this study for the psychometric assessment due to a variety of disease- and treatment-related variables in patients with neck pain. Lastly, for a complete validation of the scale, other criteria, such as interpretability, by means of minimum clinically important difference, or responsiveness, using minimum detectable change, should also be tested. It is unclear that the difference in pre- and postoperative scores is the proper approach to validate responsiveness in the absence of a comparison against a known gold standard.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Neurosurgery Unit at Imam-Hossain Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

2. Tetreault LA, Kopjar B, Vaccaro A, et al. A clinical prediction model to determine outcomes in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy undergoing surgical treatment: data from the prospective, multicenter AOSpine North America study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013 95:1659ŌĆō1666. PMID: 24048553.

3. Traynelis VC, Arnold PM, Fourney DR, Bransford RJ, Fischer DJ, Skelly AC. Alternative procedures for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: arthroplasty, oblique corpectomy, skip laminectomy: evaluation of comparative effectiveness and safety. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013 38:S210ŌĆōS231. PMID: 24113359.

4. Vernon H. The Neck Disability Index: state-of-the-art, 1991-2008. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 31:491ŌĆō502. PMID: 18803999.

5. Leak AM, Cooper J, Dyer S, Williams KA, Turner-Stokes L, Frank AO. The Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire, devised to measure neck pain and disability. Br J Rheumatol 1994 33:469ŌĆō474. PMID: 8173853.

6. Jordan A, Manniche C, Mosdal C, Hindsberger C. The Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1998 21:520ŌĆō527. PMID: 9798180.

7. Bolton JE, Humphreys BK. The Bournemouth Questionnaire: a short-form comprehensive outcome measure. II. Psychometric properties in neck pain patients. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 25:141ŌĆō148. PMID: 11986574.

8. Wheeler AH, Goolkasian P, Baird AC, Darden BV 2nd. Development of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale: item analysis, face, and criterion-related validity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999 24:1290ŌĆō1294. PMID: 10404569.

9. Westaway MD, Stratford PW, Binkley JM. The patient-specific functional scale: validation of its use in persons with neck dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998 27:331ŌĆō338. PMID: 9580892.

10. Benzel EC, Lancon J, Kesterson L, Hadden T. Cervical laminectomy and dentate ligament section for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Spinal Disord 1991 4:286ŌĆō295. PMID: 1802159.

11. Azimi P, Shahzadi S, Benzel EC, Montazari A. Measuring motor, sensory and sphincter dysfunctions in patients with cervical myelopathy using the modified Japanese Orthopedic Association (mJOA) score: a Validation Study. World Spinal Column J 2012 3:91ŌĆō97.

12. Azimi P, Rezaei O, Montazeri A. An outcome measure of functionality and quality of life in patients with cervical myelopathy. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014 16:e8102PMID: 25068064.

13. Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain 1972 95:87ŌĆō100. PMID: 5023093.

14. Nurick S. The natural history and the results of surgical treatment of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain 1972 95:101ŌĆō108. PMID: 5023079.

15. Azimi P, Mohammadi HR, Montazeri A. An outcome measure of functionality and pain in patients with lumbar disc herniation: a validation study of the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score. J Orthop Sci 2012 17:341ŌĆō345. PMID: 22538438.

16. Chiles BW 3rd, Leonard MA, Choudhri HF, Cooper PR. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: patterns of neurological deficit and recovery after anterior cervical decompression. Neurosurgery 1999 44:762ŌĆō769. PMID: 10201301.

17. Prolo DJ, Oklund SA, Butcher M. Toward uniformity in evaluating results of lumbar spine operations: a paradigm applied to posterior lumbar interbody fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1986 11:601ŌĆō606. PMID: 3787326.

18. Herdmann J, Linzbach M, Krzan M,The European myelopathy score. Baucher BL, Brock M, Klinger M, editors. Advances in neurosurgery. Berlin: Springer; 1994. p.266ŌĆō268.

19. Misterska E, Jankowski R, Glowacki M. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Neck Disability Index and Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale for patients with neck pain due to degenerative and discopathic disorders: psychometric properties of the Polish versions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011 12:84PMID: 21529360.

20. Yapali G, Gunel MK, Karahan S. The cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale in patients with chronic neck pain: Turkish version study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012 37:E678ŌĆōE682. PMID: 22281488.

21. Forestier R, Francon A, Arroman FS, Bertolino C. French version of the Copenhagen neck functional disability scale. Joint Bone Spine 2007 74:155ŌĆō159. PMID: 17011225.

22. Ferraz MB. Cross cultural adaptation of questionnaires: what is it and when should it be performed? J Rheumatol 1997 24:2066ŌĆō2068. PMID: 9375861.

23. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993 46:1417ŌĆō1432. PMID: 8263569.

24. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 25:3186ŌĆō3191. PMID: 11124735.

25. Dadasberv VY, Rodts GE Jr,Degenerative disease of the spine. Winn HR, Youmans JR, editors. Youmans neurological surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2011. p.2859ŌĆō2868.

26. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.

Table┬Ā2

Descriptive statistics for the three Copenhagen neck Neck Functional Disability Scale subscales (n=93)

Table┬Ā4

Item-scale correlation matrix for the three Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale subscalesa) (n=93)

a)Pearson correlation (r) equal to or greater than 0.40 was considered satisfactory (correlation Ōēź0.81-1.0 as excellent, 0.61-0.80 very good, 0.41-0.60 good, 0.21-0.40 fair, and 0.0-0.20 poor) [14].