Effect of Spinal Cord Injury on Quality of Life of Affected Soldiers in India: A Cross-Sectional Study

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

A prospective cross-sectional study with convenience sampling approach was done to assess quality of life (QoL) in 100 soldiers and veterans affected by spinal cord injury (SCI).

Purpose

SCI affects almost every aspect of the life of an affected individual. This study was done to measure the impact of SCI on QoL of affected soldiers and veterans using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire.

Overview of Literature

The devastating effect of SCI on QoL is well known. However, this study is unique in that it includes soldiers and veterans, who constitute a large, but excluded, cohort in most demographic studies.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was done at two SCI rehabilitation centres of the Indian armed forces. Data was collected by face-to-face interviews from 100 patients, which included both sociodemographic data as well as all the questions included in WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Results

Age and marital status did not have any influence on QoL. Level of injury (paraplegic or quadriplegic), level of education and presence of other medical co-morbidities had the most significant influence on QoL. Presence of other medical co-morbidities had a negative influence on QoL.

Conclusions

Identification of factors having a positive and negative influence on QoL help in formulating measures and policies that positively influence the QoL following SCI in soldiers. Future longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and assessment of additional variables in addition to WHOQOL-BREF, like presence/absence of secondary complications, are required to bring about policy changes to provide SCI patients with additional support and increased access to equipment or lifestyle interventions.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is possibly the most disruptive and traumatic event that can occur in anyone's life. SCI poses huge challenges in the form of coping process as well as rehabilitation. SCI may cause quadriplegia or paraplegia depending on the level of injury affecting the functioning of limbs, trunk, pelvic organs, bladder and bowel, as well as sexual function. This loss of function leads to significant changes in life of the affected individual making routine vocational, social, sexual and recreational activities impossible. Although some individuals do recover partial capacity to perform certain activities of daily living through rehabilitation, many activities are permanently altered (e.g., assisted walking with support, micturition by supra-pubic pressure) [1].

The main goal of all rehabilitation programmes is to enable the SCI affected individual to enhance their quality of life (QoL). QoL is defined by World Health Organization (WHO) as the "person's perception of his/her position in life within the context of the culture and value systems in which he/she lives and in relation to his/her goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. It is a broad-ranging concept incorporating, in a complex way, the person's physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and relationship to salient features of the environment"[2]. Recent advances in medical management as well as prevention of complications in SCI patients have improved the life expectancy and reduced the severity of the disability [3]. Therefore, it is important to measure the QoL to determine the success of rehabilitation programmes for SCI patients.

QoL in SCI patients has been specifically defined as living with independence, living with self-esteem and living well without suffering [4]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire is an exhaustive tool that clearly assesses life perspective of persons in any study, measures patient reported outcome and has been validated in multiple studies to measure QoL in SCI affected individuals [567].

Although SCI is definitely a traumatic event for all the affected individuals, it is particularly devastating for soldiers who have always been functioning at a level of physical ability and mental toughness, which is considered much higher than the community from which these soldiers hail. Even after completing their rehabilitation, the relationship of SCI affected soldiers with their family and peers is likely to be permanently altered physically, socially as well as psychologically [1].

Research has mainly focused on disability management in SCI patients. There have been very few studies to evaluate QoL in SCI patients [58910]. There are significant gaps in our knowledge in understanding how QoL is affected by SCI. The aim of this study was to evaluate how SCI affects QoL in affected soldiers and to measure the impact on different components of QoL. SCI affected soldiers constitute a very different cohort as compared to general population. While studies have been conducted to measure QoL in veterans, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first ever study in which QoL has been measured in SCI affected soldiers, a cohort that is excluded in most demographic studies.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional design with convenience sampling approach was used to recruit participants in this study from August 2014 to December 2014. The study population included all SCI patients admitted in two SCI rehabilitation centres located at Pune, India. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of traumatic SCI, age between 20–65 years, rehabilitation done after the acute phase following SCI was over and willingness to participate in the study. Unconscious patients, patients in acute phase following SCI, patients with psychiatric impairment and patients with paraplegia/quadriplegia due to non-traumatic cause were excluded. Refusal for consent also led to exclusion.

A total of 110 individuals were invited to participate in this study and 103 agreed to participate, providing an overall response rate of 93.64%. Face-to-face bedside interviews were conducted with each patient by trained volunteers after obtaining informed consent of each patient. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional Research Ethics Review Committee. The invited participants were clearly informed that participation was on a voluntary and confidential basis, with no penalty for non-completion or non-participation in the survey, and that this would not have any effect on their treatment. Participant's confidentiality was assured by using codes instead of their names for both paper questionnaires and electronic dataset.

1. Measures and instrument

The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire [10] was the primary tool to collect information on QoL of SCI patients. In addition, sociodemographic data including age, gender, education level and marital status were also collected from each participant. About 30 minutes were spent in completing the questionnaire for each patient by trained interviewers.

The WHOQOL-BREF is a shorter version of the original instrument, the WHOQOL-100, and is designed to be more convenient for use in large research studies or clinical trials [71112]. All 26 items in the WHOQOL-BREF are based on a five-point Likert Scale. Among these items, 24 items are grouped under four domains of QoL: physical health (7 items), psychological well-being (6 items), social relationships (3 items) and environment (8 items). In addition, there are another two items that are examined separately. One item is an individual's overall perception of QoL and the other is an individual's overall perception of their own health. WHOQOL-BREF demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency and validity among SCI patients [5].

The 24 items in the domains are as follows:

-

1) Physical health Activities of daily living

- Dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids

- Energy and fatigue

- Mobility

- Pain and discomfort

- Sleep and rest

- Work Capacity

-

2) Psychological bodily image and appearance

- Negative feelings

- Positive feelings

- Self-esteem

- Spirituality/religion/personal beliefs

- Thinking, learning, memory and concentration

-

3) Social relationships

- Personal relationships

- Social support

- Sexual activity

-

4) Environment

- Financial resources

- Freedom, physical safety and security

- Health and social care: accessibility and quality

- Home environment

- Opportunities for acquiring new information and skills

- Participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities

- Physical environment (pollution/noise/traffic/climate)

- Transport

2. Scoring the WHOQOL-BREF

The four domain scores denote an individual's perception of QoL in each particular domain. Domain scores are scaled in a positive direction (i.e., higher scores denote higher quality of life). The mean score of items within each domain is used to calculate the domain score.

The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was scored after its administration to the study subjects and the raw scores were converted to transformed scores. The first transformation converted scores to a range of 4–20 and the second transformation converted domain scores to a 0–100 scale. Higher scores reflected a better QoL.

The complete enumeration method was applied. As per requirements of WHOQOL-BREF, any assessment with more than 20% data missing was discarded. If an item was missing, the mean of other items in the domain was substituted. If more than two items were missing from a domain, the domain score was not calculated. However, this final rule did not apply to the physical domain, which was calculated only if a single item was missing.

3. Statistical analyses

Data was tabulated and analysed using Windows version of Statistical Package for Social Sciences, ver. 22 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and crosschecked twice. The socio-demographic data was analysed through descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages). Bivariate analysis including Student's t-test was done to study the association between QoL domains for SCI patients (paraplegic and quadriplegic). Chi square test was done to compare the differences between healthy and unhealthy (patients with other medical comorbidities) groups. One-way analysis of variance, Pearson correlation coefficient test and multivariate linear regressions were applied to determine the factors associated with physical, psychological, social functioning and environment QoL domains. The regression analysis was used to obtain the model predicting QoL. Collinearity among independent variables was tested and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Finally, we used four linear regression models to study the factors associated with QoL among the SCI patients. Since multiple models were applied and considering the sample size of our study, Bonferonni correction of the alpha value was used. The significance level for the estimates was an alpha value of 0.05.

Results

Of the 110 patients, responses were obtained from 103. Among these, data analysis was possible for 100 patients as the responses were incomplete from 3 patients. The total response rate was 93.64%.

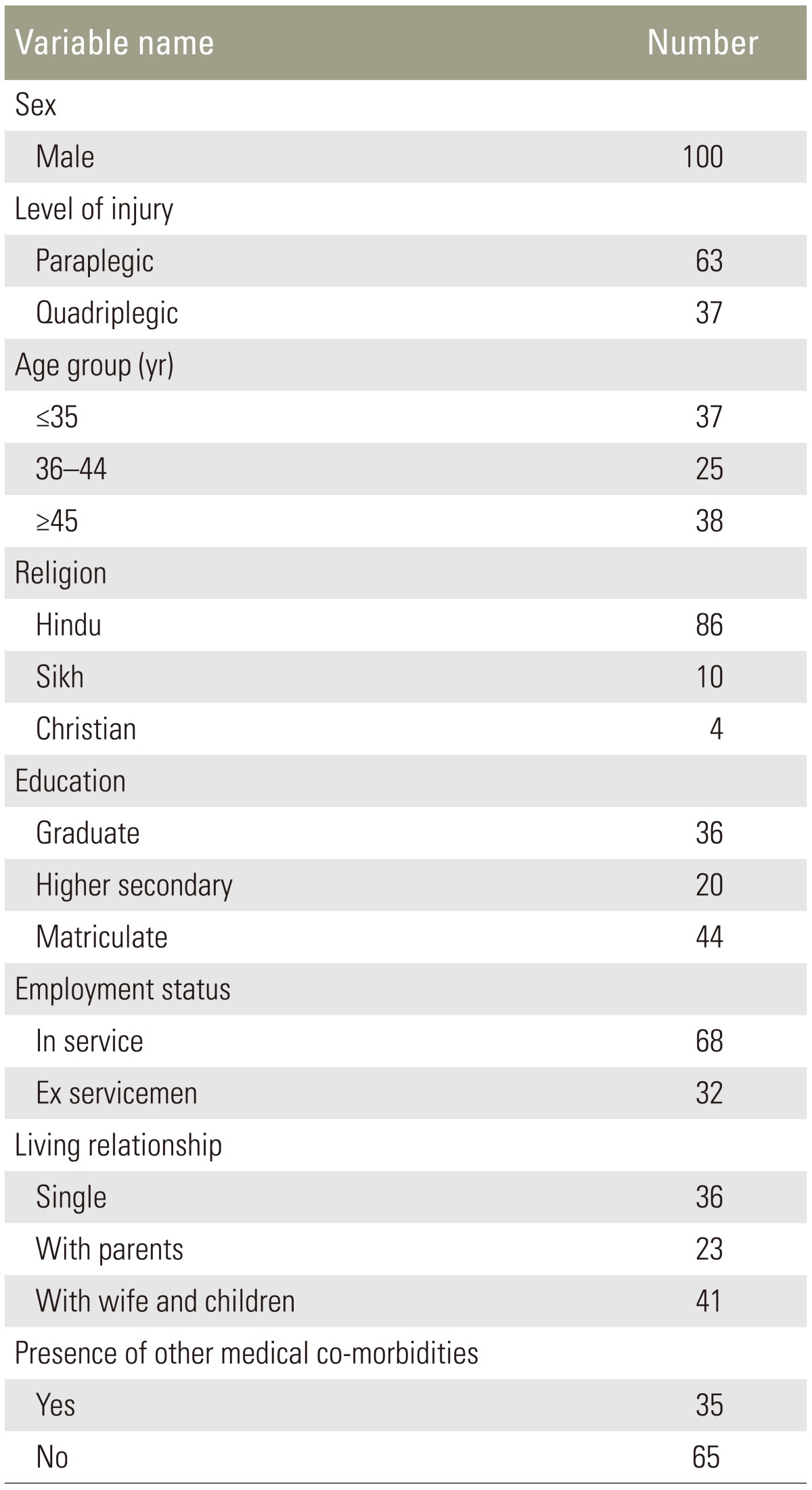

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and biographical characteristics of the sample including age group, gender, religion, area of residence, employment status, living relationship and health status (in terms of any existing medical comorbidities). Participants were between the ages of 22 to 71 years with a mean±standard deviation (SD) of 41.3±12.0 years. All 100 participants were males from the Indian Armed Forces, irrespective of their current employment status in the armed forces. Sixty eight were serving in the armed forces at the time of study and 32 were veterans. Sixty three patients were paraplegic and 37 were quadriplegic. Forty-one were married and were living with their wife and children, 36) were single and 23 were living with their parents. There was a special provision for families to stay in both the centres. Thirty five of the patients suffered from chronic diseases like hypertension, diabetes or bronchial asthma. The remaining 65 patients were healthy with no known co-morbidities. Ninety four patients had sustained the SCI in circumstances attributable to military service, while 6 had sustained injury in circumstances not related to military duty.

Cronbach's alpha coefficient (internal consistency index) was used to estimate the reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF (measured as 0.81 in the study population; Cronbach alpha coefficient values >0.70 were considered acceptable). The highest mean score±SD was reported for environment domain of QoL (25.96±3.88) and the minimum mean and SD was reported for social functioning (7.22±1.96). The psychological health domain had a score of 18.09± 3.46 compared to 21.86±3.61 for the physical health domain.

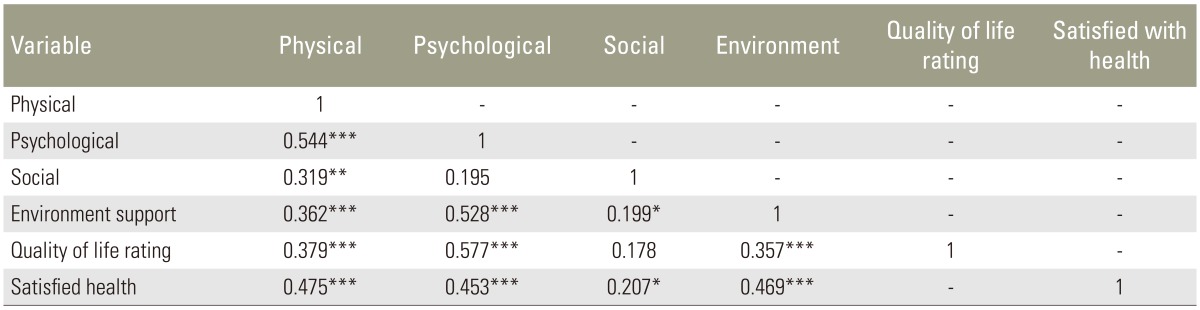

The inter-relationships between four domains of WHOQOL-BREF with each other and with overall QoL were assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. As summarized in Table 2, there was very strong evidence of correlation between the physical, psychological and environmental domains with an overall rating of QoL and satisfaction with health (p<0.001). There is no association of the social domain with psychological health or overall QoL (p>0.05).

1. Bivariate analysis

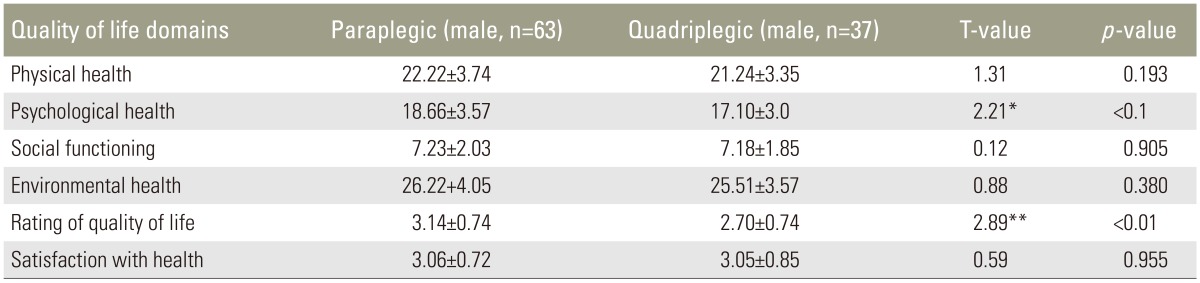

Student's t-test was done to look for associations between various domains of WHOQOL-BREF with level of injury among the patients, i.e., paraplegic or quadriplegic. The mean scores and standard deviations for four QoL domains as well as overall rating of QoL in paraplegic and quadriplegic patients are summarized in Table 3. Significant differences were evident between the paraplegic and the quadriplegic patients with paraplegics faring better (t=2.89, df=98, two tailed p=0.005). Psychological health among the paraplegic patients was better than the quadriplegic patients (t=2.21, df=98, two tailed p=0.029).

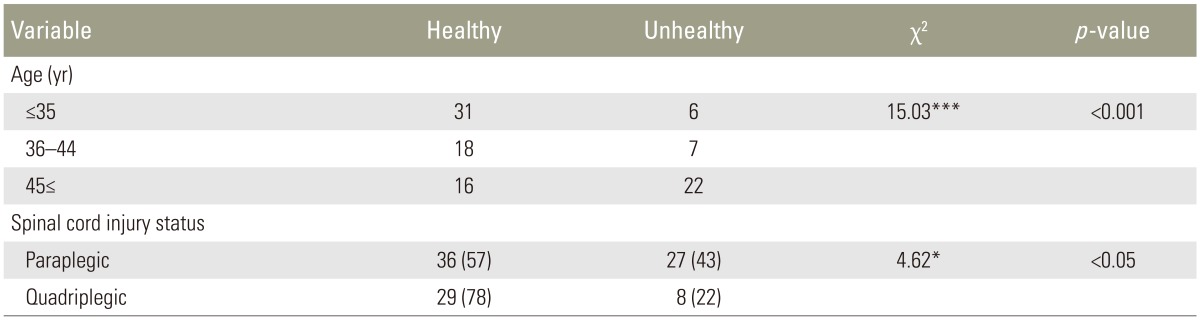

Chi square test done for comparison between 'healthy' and 'unhealthy' groups (defined in terms of existing medical comorbidities) revealed significant differences between the healthy and unhealthy group in the defined age groups (Table 4). Compared with the younger age group, the older group reported more health problems (χ2=25.49; p<0.001).

Chronic health problems (Medical co-morbidities) by demographic characteristics and their spinal cord injury status

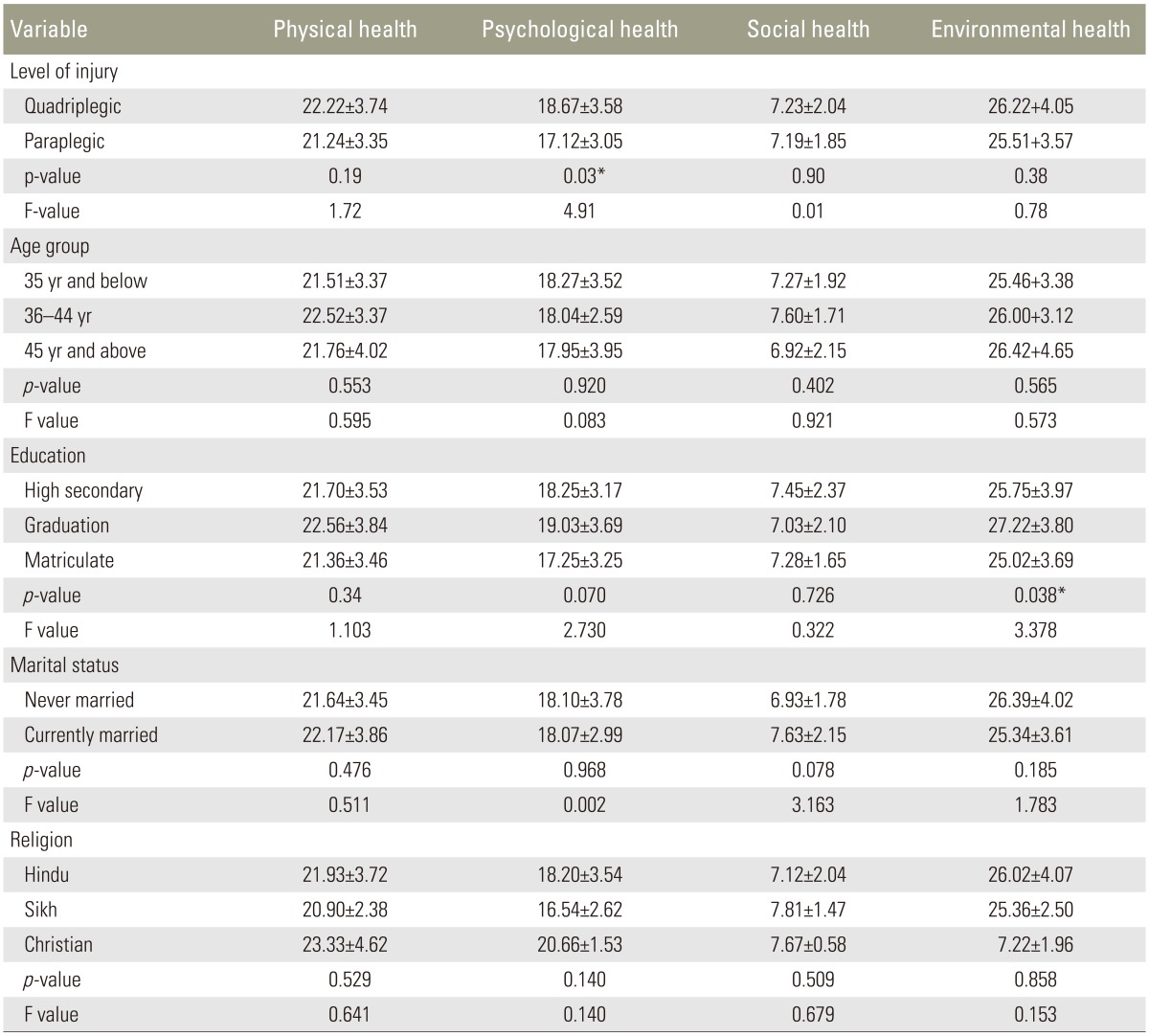

Association between patient's sociodemographic char-acteristics and WHOQOL-BREF QOL domain scores was assessed using bivariate analysis. Results are provided in Table 5. Sociodemographic variables and patient status by diagnosis were correlated with QoL dimensions. Paraplegic patients displayed better psychological health compared to quadriplegic patients (p<0.05). Similarly, patients with higher level of education had better psychological and environmental health. There was a significant linear relationship between satisfaction with health and physical and psychological QoL domains. There was also a positive relationship between psychological health and overall QoL among the SCI patients.

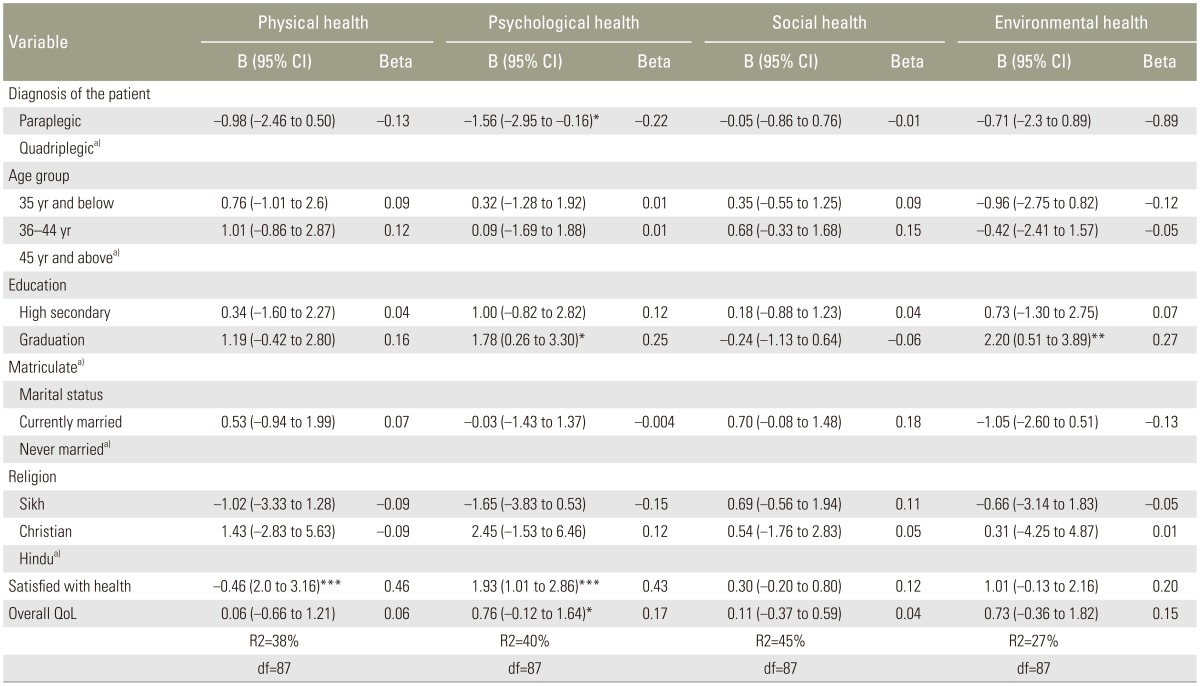

2. Multivariate analysis

Multivariate regression analysis was done to study the associations between patient's characteristics and WHOQOL-BREF domain scores, satisfaction with health and overall QoL rating. The results are summarized in Table 6. Sociodemographic variables and status of the patient by level of injury were correlated with WHOQOL-BREF domain scores. There was a significant linear relationship between better psychological health of paraplegic patients as compared to quadriplegic patients with a regression coefficient of –1.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], –0.16 to 2.95; p<0.05). Similarly, patients with higher level of education (graduation level) had better psychological domain scores with a regression coefficient of 1.78 (95%CI, 0.26 to 3.30; p<0.05) and environmental domain scores with a regression coefficient of –2.20 (95% CI, –0.51 to 3.89; p<0.01). There was a significant linear relationship between patient self-perceived satisfaction with their physical health, with a regression coefficient of –0.46 (95% CI, 2.0 to 3.16; p<0.001) as well as psychological QoL domains, with a regression coefficient of 1.93 (95% CI, 1.01 to 2.86; p<0.001). There is also an evidence of a positive relationship between psychological health and overall QoL among the SCI patients, with a regression coefficient of 0.76 (95% CI, –0.12 to 1.64; p<0.05). The total variance explained in the linear regression model was 38% by the physical domain, 40% by the psychological domain, 45% by the social domain and 27% by the environmental health domain.

Discussion

SCI has a devastating effect on quality of life. This study was conducted to measure the QoL in SCI affected soldiers and veterans who sustained SCI during active service using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire. Mean scores of different domains of QoL (i.e., physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships and environment) were measured. This study is unique as it is the first study conducted among Indian soldiers and veterans suffering from SCI. Soldiers and veterans constitute a large cohort which is excluded in most demographic studies.

Traumatic SCI affects males predominantly, more commonly in the age group of 21 to 35 years who are among the most productive and active part of any demographic group including the armed forces [101314]. Male predominance was true in our study (100%), which was expected since the composition of Indian armed forces is predominantly male, with females being inducted only at the officer level. Therefore, any gender variation could not be assessed in this study. Other studies have also shown male predominance in the affected population [410].

Age and marital support did not significantly influence any of the domains of QoL. This was quite contrary to earlier reports that age significantly affects the physical, psychological and social domains of QOL [15]. Marital status also influences social and environmental domains [16], although this was not apparent in our results. This may be due to the environment of the rehabilitation centres for soldiers as well as veterans, where abundant infrastructure and resources are available to support the injured soldiers, reducing the dependence on the families/spouses. Since most soldiers tend to live away from families in the line of duty for prolonged duration, this may also be a contributory factor in reducing the influence of marital status on QoL. Although the dominant religious denomination was Hindu, religion also did not have any significant influence on any domain of QoL.

Among all the sociodemographic factors assessed in this study, level of injury (paraplegic or quadriplegic), level of education and presence of other medical co-morbidities showed the most significant influence on QoL. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that paraplegic patients rated their QoL much higher than quadriplegics. Similar studies in the past have shown that paraplegics have a better QoL as compared to quadriplegics, whereas few studies have shown that level of injury has no relation to the QoL. Psychological domain scores have been reported to be higher in paraplegic patients than quadriplegic patients [1517]. Among all the QoL variables assessed in this study, individual's self-rating of QoL was most influential.

There is only one study available in literature assessing influence of presence of other medical co-morbidities in SCI patients on their QoL which also showed similar negative influence [18]. Level of education also significantly influenced the QoL as graduates had higher scores in environment and psychological domains, which is not consistent with past studies [19].

1. Study limitations

The nature of the study sample population (soldiers and veterans) is unique and the findings may not be applicable to the general population. In addition, no data was collected regarding prevalence/incidence of secondary complications like urinary tract infections and pressure sores and their influence on QoL. Also, this was a cross-sectional study and further longitudinal studies with larger sample size are required to assess the QoL across the lifespan in terms of age as well as time from injury. These studies would enable optimization of rehabilitation and support services required for optimal functional recovery as well as prevention of secondary complications.

Conclusions

This study measured the QoL in Indian soldiers affected by SCI using WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, which is a patient-measured and validated method in terms of reliability and reproducibility. QoL of SCI affected soldiers and veterans were positively affected by higher levels of education and lower level of SCI. Presence of other medical co-morbidities negatively influenced QoL. Future longitudinal studies with larger sample size and assessment of additional variables, like presence/absence of secondary complications, are required to assess QoL of soldiers and veterans. This may bring about policy changes to provide them with additional support and increased access to equipment or lifestyle interventions as identified.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.