Total Excision of a Giant Ventral Midline Cervical Spinal Intradural Schwannoma via Posterior Approach

Article information

Abstract

Schwannomas are the most common intradural extramedullary tumors of the spine. They usually occupy a posterolateral or lateral position in relation to the cord. The ventral midline is a very rare location for the origin of a spinal schwannoma. A giant one in such a location causes technical difficulties in excision. Here, we present a giant cervical spinal schwannoma, located ventral to the cord, in a 38-year-old lady who presented with features of myelopathy and bladder involvement. Magnetic resonance imaging was suggestive of an intradural extramedullary lesion extending from cervico-medullary junction to the third dorsal vertebral level with severe cord compression. The same was excised totally via a posterior approach after midline suboccipital craniectomy and C2–C6 laminoplasty. Postoperatively, she made a good recovery and was ambulant without support. Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging showed complete excision of the tumor. Histopathology was suggestive of schwannoma.

Introduction

Schwannomas are the most common intradural, extramedullary spinal tumors [1], usually occurring posterior or posterolateral to the cord [2]. Anterolateral location is seen in less than 5% of schwannomas, consistent with ventral root origin [3]. Giant schwannomas are those that extend over more than two vertebral body levels [4]. Ventral midline location of a giant cervical spinal schwannoma is a very rare entity [456789]. Usually, such tumors will have to be approached posteriorly, as the anterior approach will require multiple levels of corpectomy and fixation. Surgical excision of such large tumors can lead to significant postoperative deficits unless utmost care is taken, especially while manipulating the tumor beneath the ribbon-like stretched cord.

Technical Note

A 38-year-old lady with no comorbidities, presented with a five-year duration of neck pain and one-year duration of paresthesia in all the extremities, with no Lhermitte symptom. She had gradually progressing weakness of the limbs since the past one year, which had progressed to an extent that she could walk only with support. Since the past four months, she also had a history of straining while micturition, with no history of trauma, tuberculosis or features of raised intracranial pressure. She did not have a short neck or neurocutaneous markers. Neurological examination revealed hypertonia in all the limbs, with grade 4 power in the right side and grade 4 power in the left side. She had generalised hyperreflexia with extensor plantar and an absent jaw jerk. She had wasting of small muscles of the right hand and sensory dullness from C3 dermatome downwards. There was no papilledema or evidence of cranial nerve palsy.

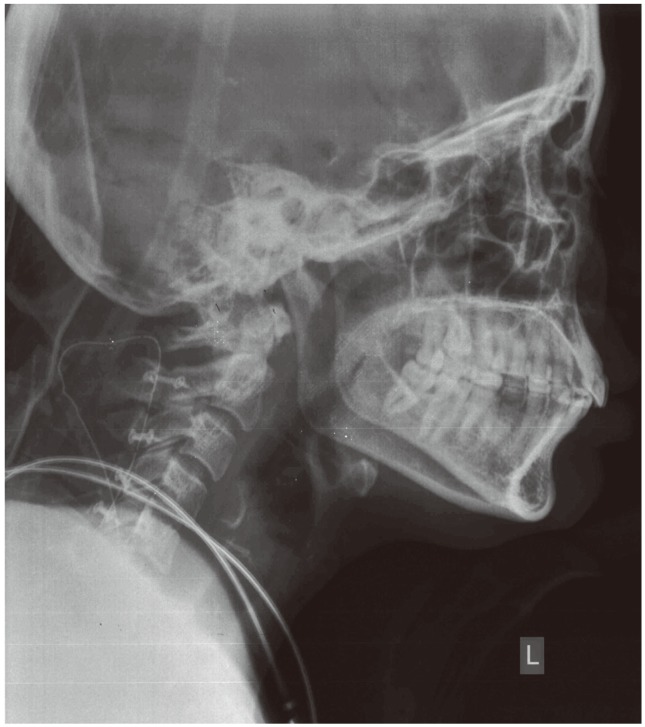

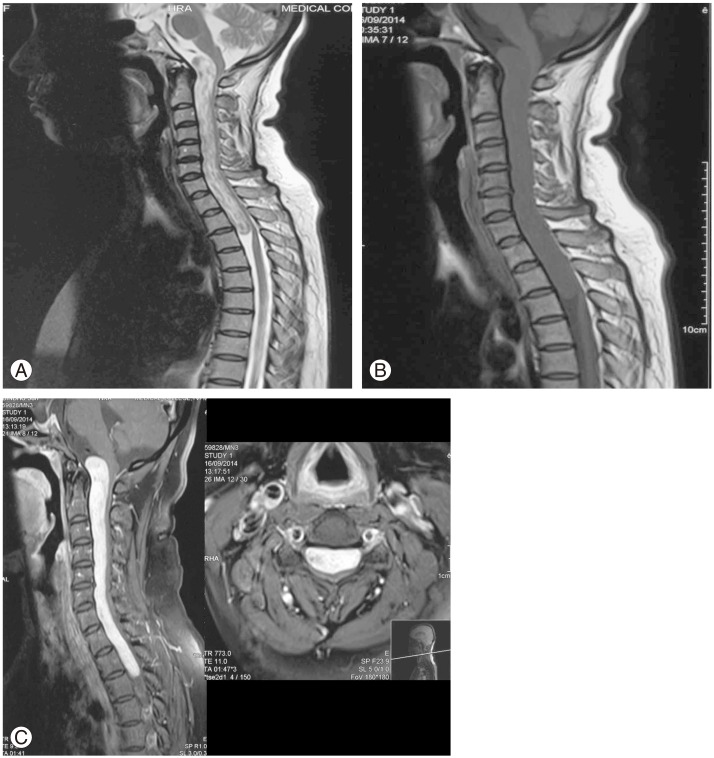

Cervical spine X-ray showed widening of the spinal canal (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine showed a long segmental T2 heterogeneous intradural, extramedullary lesion measuring 15×1.5 cm, extending from cervicomedullary junction to T3 level, with compression and posterior displacement of the cord (Fig. 2A). The cord was band-like with a thickness of 2 mm. The lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2B) with intense heterogeneous contrast enhancement (Fig. 2C). The radiological differential diagnoses were hemangioblastoma, meningioma and schwannoma. Due to the increased vascularity noted, we did a four-vessel digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) to identify the feasibility of preoperative embolization. There was no indication of a prominent arterial feeder or tumor blush (Fig. 3).

Plain X-ray of the cervical spine anteroposterior and lateral views showing widening of the spinal canal. Scale bar=10 mm.

(A) T2-weighted image (WI) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine (mid-sagittal) showing the giant heterogeneous intradural, extramedullary lesion. (B) T1-WI (mid-sagittal) image showing the hypointense lesion. (C) Gadolinium enhanced MRI (mid-sagittal and axial) showing the intense heterogeneous contrast enhancement.

Four vessel digital subtraction angiogram showing the absence of prominent arterial feeder or tumor blush.

In the prone position, we did a midline suboccipital craniectomy with excision of posterior arch of C1 and C2–C6 open-door laminoplasty with hinge on the left side, via a vertical midline incision extending from inion to T1. After opening the dura vertically, the superior extent of the tumor was seen reaching up to the lower medulla. The tumor was approached from the right side after dividing the dentate ligament. It was greyish-white, suckable and soft with some firm areas, moderately vascular, and had a well-defined capsule with definite plane with the cord. The tumor was internally decompressed using the cavitron ultrasonic aspirator, starting from C3 level downwards to C5 level, and the entire tumor could be removed with minimal traction. The dura was closed primarily and laminoplasty was done with miniplates and screws.

Postoperative X-ray showed normal alignment of the spine (Fig. 4), and MRI done within 48 hours (Fig. 5) revealed no residual tumor. The patient developed a pseudomeningocele, which was managed with a lumbar drain. Her power improved gradually, and on review after six months, she had grade 4+ power in all limbs with resolving spasticity.

Postoperative gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (mid-sagittal) revealing no residual tumor.

Histopathological examination of the specimen showed ancient schwannoma having both Antoni A areas with associated Verocay bodies (Fig. 6) and Antoni B (Fig. 7) areas.

H&E stained photomicrograph (×10) of the specimen showing the hypercellular Antoni A areas with Verocay bodies.

Discussion

We report a case of pure ventral midline cervical spinal schwannoma extending from the cervicomedullary junction to T3 level. Due to myelopathy caused by the lesion, the patient could walk only with support, and had developed hesitancy of micturition. Thus, surgical intervention was justified. Preoperatively, the DSA failed to identify any prominent feeders, and we were unable to embolize the lesion. However, to an extent, we were consoled by the absence of tumor blush.

The next troublesome question was whether to approach the lesion anteriorly or posteriorly. On literature review, we found the following problems associated with an anterior approach [9]: (1) inadequate access due to deep and constrained field of view, (2) excessive bleeding from epidural venous plexus, (3) need for ensuring spinal stability and meticulous bony reconstruction, (4) postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage.

Hence, we decided to approach the tumor posteriorly. Since there was a reluctance to do multiple levels of laminectomy resulting in facet joint disruption causing instability, we planned for laminoplasty without disrupting the lateral masses. The portion of the tumor above the foramen magnum was planned to be accessed through suboccipital craniectomy. The tumor was approached from the right side, after dividing the dentate ligament on that side. We could resect the entire tumor by dividing the ligaments only at the C3–C5 levels, as the rest of the tumor could be brought into the field using minimal traction and with the aid of internal decompression. A specific root of origin for this tumor could not be identified. Several theories have been put forward to explain the origin of schwannomas at the midline ventral location [8]: (1) from perivascular nerve plexi surrounding penetrating cord vessels from the anterior spinal artery (ASA), (2) migration of neural crest progenitors into the parenchyma, (3) atypically located parent Schwann cells, such as those of the nervi vasorum of the ASA, (4) from the leptomeninges in the region of the anterior median septum.

Although multi-level laminoplasty has been proposed to cause swan-neck deformity [5], no such problem was seen in this patient during six months of follow-up. The key points for the best surgical outcome in these patients are: (1) very minimal, and if possible, no traction on the cord (2) avoiding root injury (3) not disturbing the facet joints (4) adequate primary dural closure with the application of fibrin sealant, if necessary (5) minimum use of bipolar cautery.

In conclusions, ventral midline giant cervical spine schwannomas are very rare. Such tumors can be accessed posteriorly and total excision can be done using this approach alone.

Acknowledgments

Department of Radiodiagnosis (provider of MRI images) and Department of Pathology (histopathological examination), Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

Department of Interventional Radiology (DSA provider), SCTIMST, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.