Introduction

Spinal epidural abscesses are rare, and they may have devastating consequences. They can be found in immunocompromised patients, such as intravenous drug users, diabetics, and others. Spinal epidural abscesses usually span 3~4 vertebral levels. Extensive ventral spinal epidural abscesses have been described, but are exceedingly rare. There is no consensus concerning the treatment of these extensive abscesses.

We describe a diabetic patient whose extensive ventral spinal epidural abscess was demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The patient was treated with long level laminectomy, pus drainage, and intravenous antibiotics.

Case Report

A 64-year-old female patient with diabetes mellitus began experiencing acute, bilateral, parathoracic pain on January, 2007. She visited a local clinic, but no definitive diagnosis was made. The symptoms became aggravated, and seven days later, she developed a mild fever. Hence, she presented to the hospital emergency room.

A fever of 37.6Ōäā was noted at the time of the emergency room visit. Physical examination revealed severe percussion tenderness in the thoracic area and intact deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs, such as knee jerk and ankle jerk reflexes. Muscle strength and sensory function were intact for all limbs. Grossly, we noted self-acupuncture inoculation marks on the mid- and lower back. Plain x-ray of the thoracolumbar spine revealed an old compression fracture of the L1 vertebral body and posterolateral fusion with instrumentation at L4-L5. Laboratory studies demonstrated leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 22,500 cells/mm3) and hyperglycemia (blood glucose concentration, 470 mg/dL). The glycated hemoglobin value was 9.3% (normal value: <6.0%). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 120 mm/hr (normal value: 0~26 mm/hr), and highly sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) was 187 mg/L (normal values: <8.0 mg/L). Several hours later, the patient began exhibiting altered mental status. Her fever increased to 38.6Ōäā, and she was tachycardic, with a blood pressure of 100/60 mmHg and cold, sweaty extremities. She was admitted to the endocrinology department with a diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and sepsis.

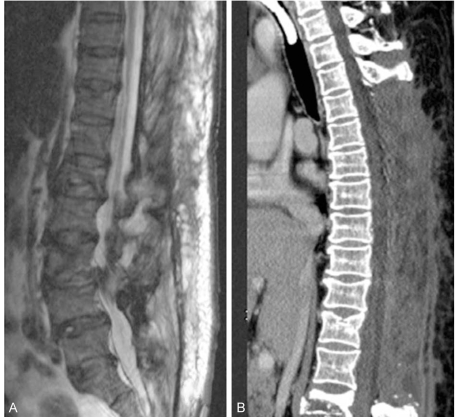

Four days later, her mental returned to normal. However, the parathoracic pain continued, and a neurologic deficit had appeared after her transfer to endocrinology. The patient was subsequently transferred to the orthopaedic surgery department for evaluation of infection focus and neurologic deficit. Neurologic examination showed grade 0/5 motor strength in the lower extremity muscle groups bilaterally and complete numbness below the T4 sensory level. Deep tendon reflexes, such as knee jerk and ankle jerk, were grade 0/4. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) and MRI studies of the whole spine revealed a ventral spinal epidural lesion (probably an abscess) extending from L1 to the upper thoracic spine (T4) (Fig. 1). The abscess caused significant compression of the cord in the thoracic region. Also noted were a psoas abscess, osteomyelitis of the L1 vertebra, and discitis at L1-L2.

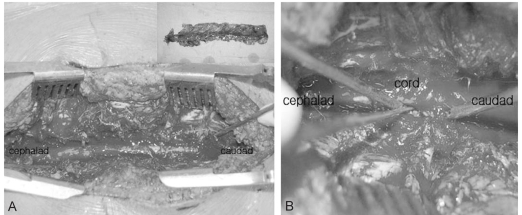

Due to neurologic deterioration, urgent surgical decompression was undertaken. The patient underwent total laminectomy of T4-T12 (Fig. 2A). Frank pus sprang up from the laminectomy site (Fig. 2B). The epidural space was irrigated with normal saline until a clear return was obtained. After repeated irrigation, a Penrose drain connected to a Hemovac drain was then inserted. The wound was then closed.

Empirical antibiotic therapy initially consisted of intravenous cefpiramide (3rd generation cephalosporin, 1 g twice daily) and isepamicin (aminoglycoside, 400 mg once daily). Methicillin-sensitive, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was identified on blood cultures. Intraoperative cultures of the epidural space also yielded methicillin-sensitive, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. The patient was treated with the above mentioned combination of antibiotics for 6 weeks.

By the second postoperative day, body temperature and sensory function had returned to normal, and the back pain had resolved. The ESR was 66 mm/hr, and CRP was 72 mg/L. However, motor function did not recover (muscle strength 0/5).

Postoperative MRI and CT of the spine (4 months after surgery) showed that the purulent debris was diminished (Fig. 3). However, further follow-up could not be done because the patient died of sepsis eight months after surgery.

Discussion

Spinal epidural abscess is an uncommon infectious disease. In the early 1970s, the incidence ranged from 0.2 to 1.2 per 10,000 hospital admissions per year, but the incidence seems to be on the rise1,2. The peak incidence occurs in the sixth and seventh decades of life. Diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug abuse, chronic renal failure, and systemic immunodeficiency are among the predisposing factors.

Pathogens can be introduced into the epidural space through hematogenous seeding, direct spread from contiguous structures, or from direct inoculation from trauma or invasive procedures. Dorsally located abscesses are usually due to hematogenous seeding of the psoas or to acupuncture-induced paraspinal hematomas by which pathogens spread to the epidural space through the intervertebral foramina. Our patient had a ventrally located abscess, which may have been associated with osteomyelitis of the L1 vertebra and discitis of L1-L2.

Spinal epidural abscesses most often occur at the lumbar level (48%), followed by the thoracic (31%) and cervical levels (21%)3. The posterior epidural space has been known to have a higher incidence of spinal epidural abscess formation, but in more recent studies, 69% of spinal epidural abscesses were located anterior to the cord, 17% posterior, and 14% anteroposterior4.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common infectious agent (45%) responsible for spinal epidural abscesses. In our case, methicillin-sensitive, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was cultured.

Spinal epidural abscesses are uncommon, but they have a high morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients. If untreated, rapid and irreversible neurologic deterioration may take place, progressing from spinal ache to root pain in 3 days, to radicular weakness in 4 to 5 days, and finally to paralysis 24 hours after that4. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are important for functional recovery. Many authors3-6 have shown that the single most important variable in determining neurologic outcome is the patient's neurologic status at the time of diagnosis and treatment. Patients who are neurologically intact at the time of surgical treatment usually retain normal neurologic function. Patients with complete paralysis for greater than 48 hours almost never recover useful neurologic function. Patients presenting with paresis of short duration often have significant recovery of function. In our case, the neurologic deficit duration was 32 hours, and the motor function did not recover.

A number of different treatment techniques have been described in the literature, from open decompression to limited decompression and percutaneous CT-guided needle aspiration5. In our case, invasive technique (multilevel laminectomy with the use of an epidural Penrose drain) proved to be effective for draining this extensive spinal epidural abscess. The advantages of posterior decompression include reduced surgical time and reduced morbidity compared with the anterior approach. Because our patient was elderly and at high risk for surgical morbidity and mortality, this advantage was highly significant. Invasive multilevel laminectomy carries with it the risk of kyphotic deformities and instability of the spine6-8. Hence, we did not violate the facet joints. In the thoracic spine, laminectomy combined with a transpedicular approach to the floor of the canal is usually sufficient to decompress an anterior abscess. Care must be taken not to retract the thecal sac.

Conclusions

Surgical decompression and antibiotic therapy are the treatments of choice for patients with spinal epidural abscesses. In our case of an extended, ventrally located spinal epidural abscess, multilevel laminectomy achieved excellent sensory function recovery, but unsatisfactory motor function recovery. Whenever this multilevel laminectomy is utilized, every effort should be made to minimize the risk of late kyphosis and instability.