Cement Augmentation of Pedicle Screw Instrumentation: A Literature Review

Article information

Abstract

This literature review aimed to review the current understanding, indications, and limitations of pedicle screw instrumentation cement augmentation. Since they were first reported in the 1980s, pedicle screw cement augmentation rates have been increasing. Several studies have been published to date that describe various surgical techniques and the biomechanical changes that occur when cement is introduced through the screw-bone interface. This article provides a concise review of the uses, biomechanical properties, cost analysis, complications, and surgical techniques used for pedicle screw cement augmentation to help guide physician practices. A comprehensive review of the current literature was conducted, with key studies, and contributions from throughout history being highlighted. Patients with low bone mineral density are the most well-studied indication for pedicle screw cement augmentation. Many studies show that cement augmentation can improve pullout strength in patients with low bone mineral density; however, the benefit varies inversely with pathology severity and directly with technique. The various screw types are discussed, with each having its own mechanical advantages. Cement distribution is largely dependent on the filling method and volume of cement used. Cement composition and timing of cement use after mixing are critical considerations in practice because they can significantly alter the bone-cement and screw-cement interfaces. Overall, studies have shown that pedicle screw cement augmentation has a low complication rate and increased pullout strength, justifying its universal use in patients with a suboptimal bone-implant interface.

Introduction

Transpedicular instrumentation has transformed the field of spine surgery by providing a dependable and robust instrumentation technique that may result in better outcomes and lower complication rates when compared to previous surgical techniques [1–4]. Pedicle screw instrumentation (PSI), which has grown in popularity over the last 2 decades, may allow for higher fusion rates, stronger biomechanical constructs, fewer instrumented levels, earlier postoperative mobilization, and lower complication rates when compared to previous instrumentation techniques and non-instrumented fusion techniques. PSI may also eliminate the need for external orthoses. With a proper surgical technique that may include varying degrees of image guidance, PSI can be performed safely and accurately with a low complication rate and reliable outcomes [5,6]. However, PSI-based constructs present a unique set of challenges, particularly in patients with low bone mineral density or anatomy that limits PSI size. PSI fixation is dependent on screw purchase in bone, which decreases in the presence of osteopenia. Furthermore, the incongruity between rigid spine implants and osteopenic bone can manifest as catastrophic implant failure given the demands on the bone-implant interface [7–9]. As such, techniques for reinforcing pedicle screws through cement augmentation have been developed to overcome this challenge. Cement augmentation of spinal hardware can be used to improve the bone-implant interface strength and pullout strength, potentially improving long-term outcomes and implant survivorship [10].

History

The use of bone cement to secure orthopedic implants can be traced back to 1890, when an innovative German surgeon, Themistokles Gluck, used plaster and colophony cement to secure a total knee prosthesis [11]. Since then, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) was developed in the middle of the 20th century and was used by John Charnley in joint replacement with excellent results, leading to its widespread use in orthopedics [12]. Zindrick et al. [13] described the concept of cement augmentation of PSI to increase pullout strength in a biomechanical study. Numerous other biomechanical studies have been published since then to support its use [14,15]. Manual cement augmentation gained popularity in the mid-1990s, but it was not until 2016 that the Food and Drug Administration approved specific instrumentation to facilitate cementation [16].

Indications

Given that cement augmentation of PSI allows for the increased biomechanical purchase of spinal instrumentation in settings with low bone mineral density, cement augmentation is recommended whenever bone quality does not allow for adequate fixation via PSI alone. Cement augmentation should be considered in conditions such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, inflammatory arthropathies, pathologic processes, radiation-induced bone necrosis, and other pathologies that may negatively impact the bone-implant interface but are amenable to cement augmentation. The cement augmentation discussed in this section would benefit the following case scenarios in terms of pullout strength and construct stability.

The most common condition where cement augmentation is beneficial is osteoporosis. Multiple risk factors have been determined for osteoporosis including increased age, tobacco use, sedentary lifestyle, and alcoholism. Secondary osteoporosis has also been linked to endocrine, gastrointestinal, and autoimmune disorders. Serum vitamin D deficiency, which is strongly linked to bone loss, is extremely common, with 40%–90% of adults being deficient [17]. Perioperative vitamin supplementation and the start of medical treatment for osteoporosis are recommended to improve spinal surgery outcomes. There is a need for research into the effect of perioperative osteoporosis management on the outcome of pedicle screw augmentation. The failure mechanism at the screw-bone interface has been reported to be directly related to the age of the spine [18]. Given that a large proportion of spine pathology is degenerative, it is not surprising that many patients who require surgery are older and thus have poor bone quality. Bone mineral density (BMD) measurements using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans are routine and can be beneficial for patients undergoing spinal instrumentation for perioperative planning. The World Health Organization classifies T scores less than −2.5 as osteoporosis, with T scores between −2.5 and −1 implying osteopenia. Screw loosening and failed fusion rates are significantly higher in patients with lower BMD [7].

Malignancy is another condition that causes osteopenia [19]. Due to the well-known valveless venous architecture, the spine is the most common location for metastatic bone tumors [20]. Tumor burden is also highest in the vertebral bodies and pedicles, posing a significant barrier to PSI [21]. Radiation therapy, which is commonly used to treat abdominal tumors, is another risk factor for osteopenia in the spine. Patients undergoing radiation therapy for visceral tumors had a dose-dependent decrease in bone mineral density and a higher risk of spine fragility fractures [22]. It is reasonable to assume that this results in poorer quality pedicle screw fixation in this subset of patients, making them candidates for cement augmentation.

PSI revision can also benefit from cement augmentation. As the use of spinal surgery increases, so does the demand for revision spinal surgery. While PSI is frequently a safe and dependable surgical technique, anatomical constraints such as pedicle size and motion-induced bone loss from prior implantation may prevent increased PSI sizes from being possible when compared to instrumentation. In these cases, cement augmentation can improve biomechanical purchase without the need for a larger screw, which could cause cortical perforation or breach [23,24].

Biomechanical Considerations

A major topic of interest is the use of pedicle screw cement augmentation to improve fixation in cases of poor bone quality, particularly in the setting of osteoporosis and revision surgeries. Most articles to date have investigated pedicle screw cement augmentation biomechanics using PMMA and cadaveric bone. Screw type, method of cementing, cement volume, timing, and material are all important considerations in optimizing pullout strength and cyclical compressive loading.

PMMA-augmented screws in cadaveric bone have a 1.2-to-2.1-fold increase in pullout strength when compared to solid screws without cement [25–27]. It has been demonstrated that screw stability is dependent on the structural characteristics of the pedicle, with the pedicle accounting for approximately 60% of PSI pullout strength rather than the vertebral body [28]. Cement augmentation can improve screw stability by increasing the local density of the pedicle. It is important to note that cement distribution varies with BMD, with more osteoporotic bone being able to accommodate a wider cement distribution pattern due to the increased porosity of this weaker bone. Pullout strength is known to have a direct negative correlation with the severity of osteoporosis caused by screw-bone failure. This principle holds for augmented screws as well, with pullout strength decreasing as bone mineral density decreases [29,30]. Fan et al. [30] discovered that maximum pullout strength in non-augmented screws decreased by 50 N for every 10 mg/mL decrease in BMD, with overall pullout strength increasing with screw augmentation. However, they conclude that in cases of severely low BMD, augmentation no longer provided a suitable benefit. In cases where BMD was below 0.6 g/cm2, PMMA augmented screws loosened [31], supporting presurgical bone quality assessment for pedicle screw candidacy even with augmentation. A definitive BMD value at which augmentation becomes significantly beneficial remains unknown because the majority of studies to date have only supported a correlational relationship between BMD and loosening in both non-augmented and augmented screws [7,14,30].

Fixation biomechanics are influenced by the method of cement insertion and screw design. The superiority of solid versus fenestrated screws in cementing remains unknown. A marked increase in pullout strength with fenestrated screws has been observed [32,33]. However, other studies have found no significant difference in failure load [34,35] or the superiority of the prefilling method [10,36]. Cement distribution and cement leakage rates differ between the two methods. Hole placement within the screw determines cement distribution. The most proximal fenestration position is critical [35]. The closer the cement is to the pedicle, the more stable the pedicle screw is [37]. Injection of 3.0 mL of PMMA through fenestrated screws with six holes resulted in cement distribution closer to the pedicle but increased the risk of leakage, leading Liu et al. [37] to conclude that the use of four-hole screws could produce optimal stability with a lower risk of cement leakage around the neural elements

1. Methods of augmentation

Several surgical techniques enable PSI cement augmentation. Techniques explained include transpedicular vertebroplasty augmentation, injecting cement directly through the pedicle and into the vertebral body followed by screw placement [38,39]; kyphoplasty augmentation, using a balloon to inflate space within the vertebral body followed by cementation and pedicle screw placement [40]; applying cement directly onto the pedicle screw before insertion [41]; and using fenestrated screws and injecting cement through the implant [42]. Because studies have not consistently demonstrated the superiority of one technique over another, the method of cementation used varies according to preference and implant availability [10,35,40].

Comparative studies typically concentrate on a single method of augmentation, making comparisons between different methods difficult. In a mechanical pullout study, Costa et al. [43] compared solid screws without PMMA (control technique) to solid screws with retrograde PMMA prefilling into a tapped pilot hole (standard technique), fenestrated screw with PMMA, kyphoplasty technique with retrograde PMMA injection before solid screw insertion, and finally a combined kyphoplasty technique with PMMA injection via a fenestrated trocar with solid screw insertion. All four techniques showed statistically significant increases in pullout strength when compared to the control technique, with the standard, and fenestrated PMMA techniques being comparable with no statistical differences. Notably, using the kyphoplasty technique with a fenestrated trocar for PMMA insertion followed by solid screw placement resulted in significantly higher pullout strength when compared to all other methods [43]. A similar study using PMMA found comparable pullout strength when using a vertebroplasty technique with solid versus fenestrated screws, but balloon kyphoplasty with solid screws did not show a significant difference in pullout strength when compared to no augmentation [35]. More research comparing various methods of augmentation and combining methodologies is required to guide clinical practice.

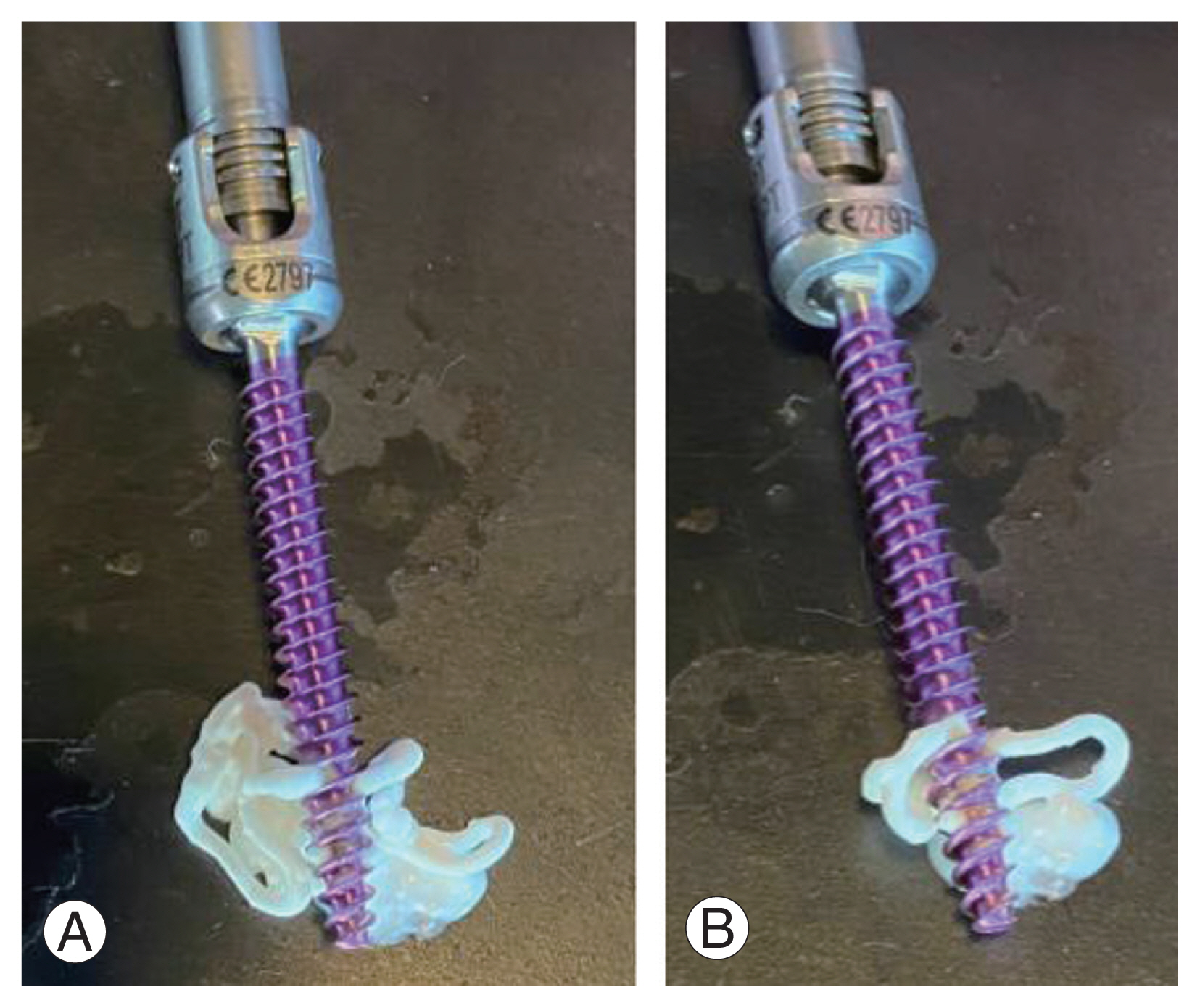

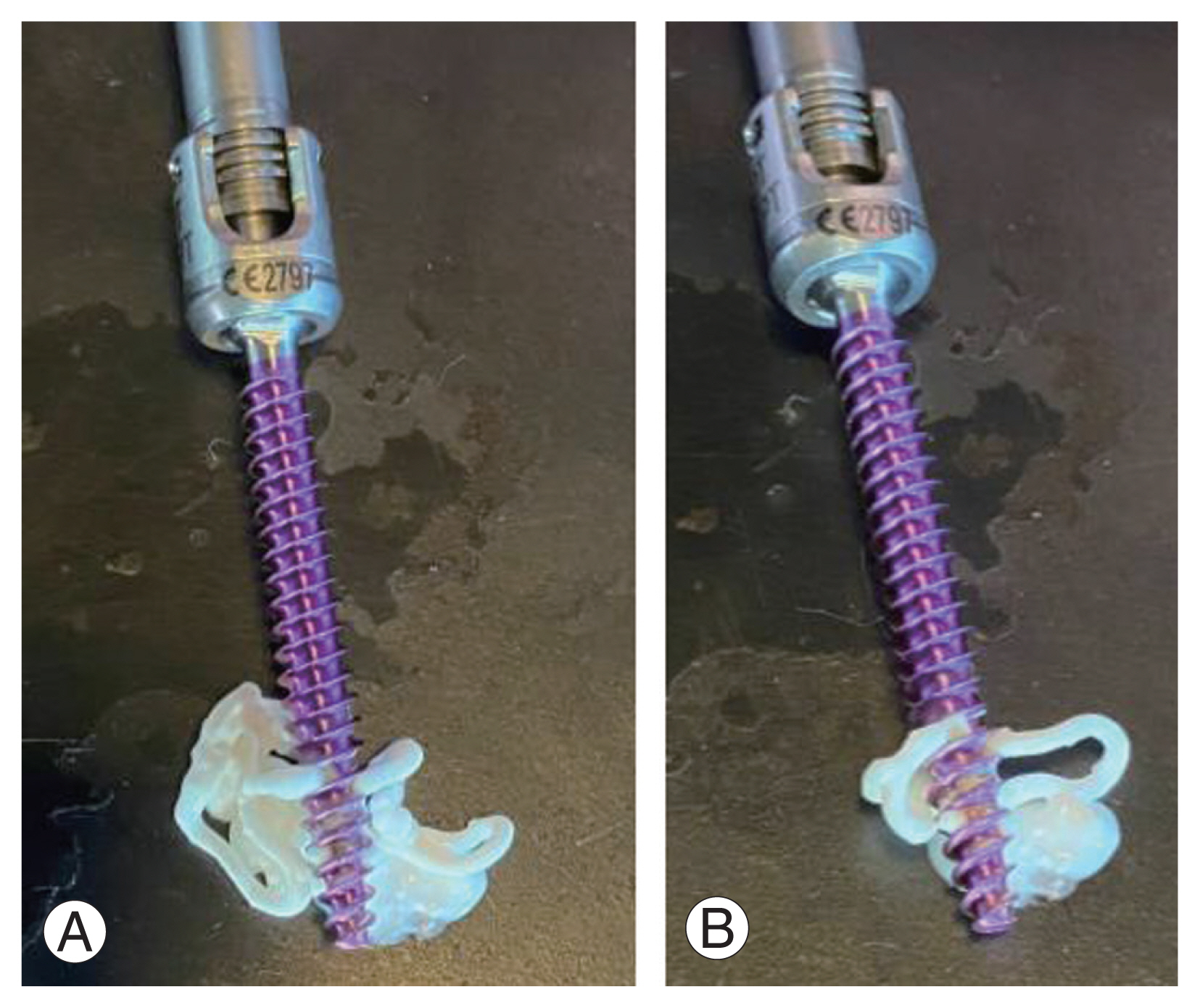

Fenestrated screws have gained popularity in recent years due to their ability to streamline the cementation process and provide a more consistent distribution of cement within the vertebral body to coat the bone-implant interface. They have a cannulated core and various windows along the length of the screw that allows the cement to flow from the screw head to the tip. Cement is injected after insertion and distributed according to the fenestration pattern. Fenestrated screws have been shown to reduce cement injection pressure, which may help prevent cement leakage [44]. Liu et al. [37] observed a significant increase in pullout strength in fenestrated screws with six holes compared to four holes when 2.0–2.5 mL of PMMA were used, most likely due to increased cement distribution near the pedicle. The distance between fenestrations, as well as their location and number, varies greatly between screw types and can affect cement distribution as well as the biomechanics of the fixation. A recent study compared various fenestrated designs to the traditional cementation method using a standard screw. Screw designs ranged from standard pedicle screws, cannulated without fenestrations, distal one-hole, distal two-hole, and middle two-hole fenestrated designs. All fenestrated designs outperformed traditional and cannulated designs in pullout strength, which is believed to be due to the cement core in the vertebral body being continuous with the cement inside the screw. The injection pressures resulted in variable cement distribution patterns with the various techniques. The traditional and middle two-hole designs had the best cement distribution across the long axis of the screw, resulting in a lower chance of leakage into the spinal canal [45] (Figs. 1–3).

(A, B) Example of a fenestrated pedicle screw demonstrating cannulated core and fenestrations for cement delivery.

(A, B) Cement delivery demonstrated in fenestrated pedicle screws. The cement will distribute through the fenestrations and take the path of least resistance. As the pressure accumulates proximally, the cement will continue distally until the entire distal portion is covered.

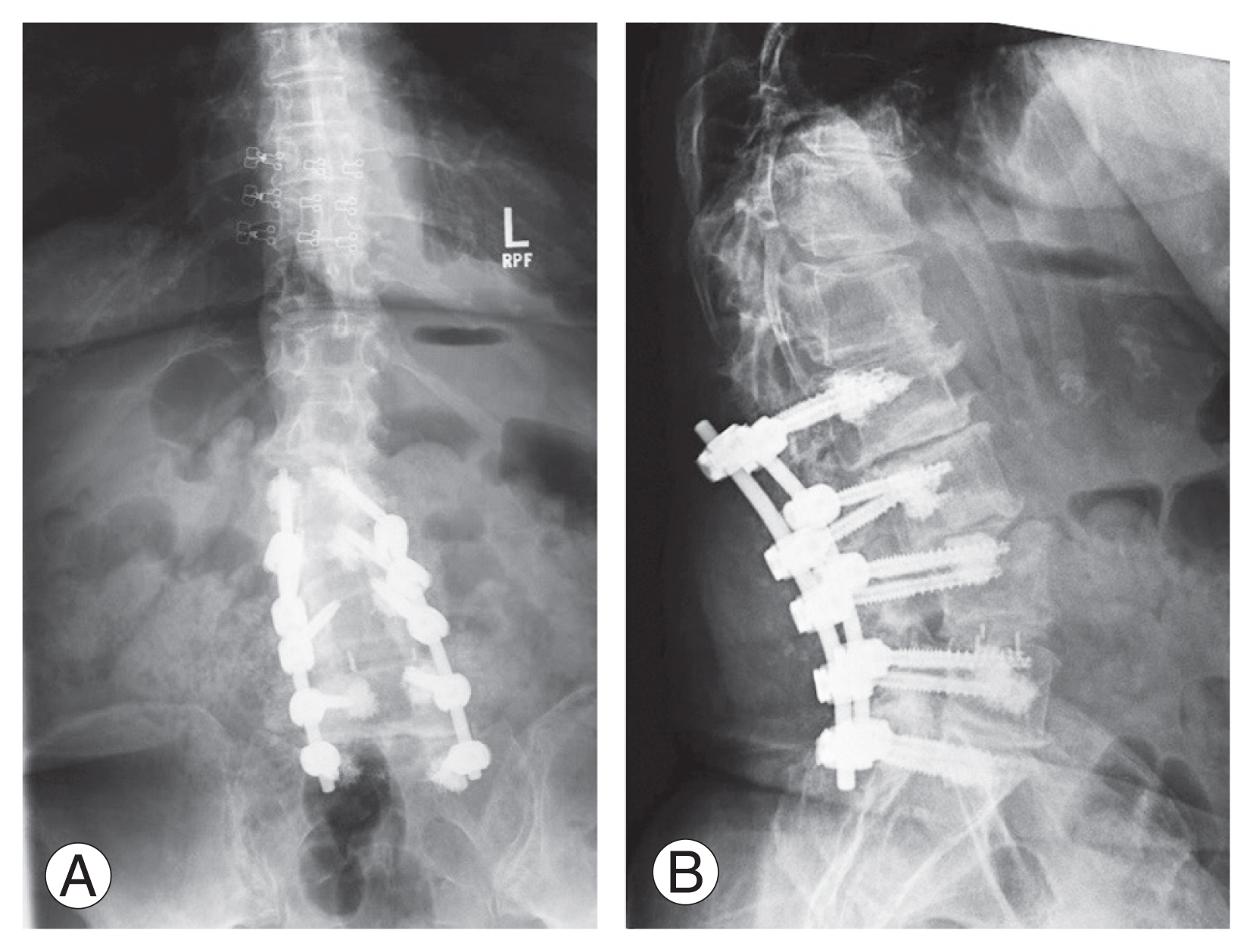

(A, B) Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the lumbar spine demonstrating fenestrated pedicle screws with cement augmentation. Written informed consent for the publication of these images was obtained from the patient. Images were provided courtesy of Laurence E. Mermelstein, MD.

2. Cement volume

Several studies have found a direct relationship between maximum pullout strength and cement filling volume [15,30,37,46–48]. Liu et al. [29] found a significant positive correlation between screw stability and PMMA volume in cadaveric osteoporotic lumbar vertebrae with varying levels of PMMA ranging from 0 to 3.0 mL. Leichtle et al. [34] discovered that 3 mL of cement had significantly lower failure rates than 1 mL. Surprisingly, only 1 mL was required to significantly improve holding power in the thoracic spine, while 3 mL was required in the lumbar spine. Contrary research has found little to no advantage of low versus high cement volumes on pullout strength [24,49]. The greatest danger of increasing cement volume is the risk of cement leakage and subsequent neurologic complications. When determining cement volume in clinical practice, physicians should consider both the biomechanical benefits of increased cement volume and the risk of cement leakage.

3. Cement timing

Screw placement after cement insertion is critical for optimizing the screw-cement and cement-bone interfaces. Early screw placement into soft cement is thought to improve screw thread integration, allowing for optimal screw-cement interaction [48]. Failure at the bone-cement interface has been shown in soft cement, as has cured cement at the screw-cement interface [48,50,51]. It is believed that inserting screws into cured cement causes cracks within the screw-cement interface, reducing its integrity. Flahiff et al. [52] discovered significantly stronger fixation when softer “doughy” cement was compared to hard cement using PMMA. Schmoelz et al. [51] discovered a significantly higher number of load cycles until failure for PMMA screws augmented after repositioning than before. Using calcium phosphate (CP) cement, Cho et al. [53] discovered augmentation power increased for up to 4 minutes before decreasing after 6 minutes. Masaki et al. [54] discovered no statistical significance between CP setting times, but they did discover that pullout strength was lowest at 10 minutes compared to 2- and 5 minutes.

4. Alternative cement materials

PMMA is the most commonly used pedicle screw augmentation cement [15]. Rapid solidification, level of stability, physician familiarity, and existing supply in most hospitals are some of the many benefits of its use. A common source of concern with PMMA is its high exothermic polymerization temperature and lack of osteoconductivity. CP and calcium sulfate (CS) are popular augmentations because they are osteoconductive and osteoinductive, allowing for normal bone remodeling over time. The fact that most studies comparing calcium-based cement to PMMA are cadaveric and test screw performance shortly after insertion is a limitation [48]. CP and CS do not provide maximal stability immediately after fixation, but rather after bony ingrowth, which is a significant difference from PMMA [15]. Moore et al. [23] discovered that both PMMA and CP restored baseline pullout strength, with PMMA increasing strength to 147% and CP increasing strength to 102%, though this difference was not statistically significant. Renner et al. [55] found that PMMA had significantly higher pullout strength than CP in both revision and augmentation cases. When comparing CP, CS, and a CP/CS mixture, Choma et al. [56] discovered a statistically significant increased resistance to failure with CP being the most resistant, followed by CS, and finally the CP/CS mixture. This disparity was thought to be due to differences in cement distribution between the materials; CP was distributed uniformly along the bony interface, whereas CS was typically absent for the distal 2–3 threads. Silicone is another osteoconductive material in use, which has been shown to have significantly higher loading cycles than PMMA [57,58].

Distribution varies between cement materials. As a result, comparing the biomechanical properties of each cement using different augmentation methods and screw types is critical. Data is scarce because cement augmentation with alternative materials is relatively new, and most studies to date have focused on the use of PMMA. Sun et al. [59] found marginal pullout strength differences in cannulated screws made of CP versus PMMA, and overall pullout strength was higher in cannulated screws made of both materials compared to solid screws.

There are various cement and screw types used, as well as various instrumentation methods. Overall, biomechanical data supports the use of cement augmentation to improve the strength of the construct implanted.

Cost Analysis

The cost of cement augmentation is determined by the equipment and technique used. Literature is scarce on the costs of PSI with cement augmentation. We calculated the costs of our healthcare system by averaging values from several manufacturers. The manual method of prefilling the transpedicular tract and inserting screws is the most affordable. This involves two standard pedicle screws, cement (PMMA), and a cement mixing kit, all of which cost around $1,000. Adding vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty to introduce cement raises the cost significantly. Kyphoplasty/vertebroplasty kits cost around $2,400, in addition to the cost of instrumentation. Using newer and more specialized fenestrated instrumentation (two fenestrated screws with cement, mixing kits, and disposable injectables), costs approximately $2,400 per level.

Complications

The unique complications of cement augmentation during PSI include cement extravasation, pressurization, and difficulty in removal after setting. These complications are similar to those seen with other orthopedic hardware cemented implantations, such as cemented joint arthroplasty. These complications range from minor to severe. Extravasation into the disk space is harmless, but it has the potential to increase the risk of future fractures in adjacent segments, so it should be avoided [60]. Extravasation into paravertebral soft tissues is harmless and has no clinical implications. Cement extravasation into the foraminal space or spinal canal has the potential to cause catastrophic damage due to the proximity of neural elements. Even if such extravasation occurs, it is usually clinically insignificant. One study incidentally showed cement extravasation in 40% of post-procedural computed tomography (CT) after vertebroplasty [61]. The rate of neurologic deficits caused by cement augmentation has been reported under 0.5% [62]. Although extremely rare, extravasation into the epidural vein system has been reported, with the potential for severe consequences through embolization. Data is limited to a few case reports, but Choe et al. [63] discovered evidence of small pulmonary embolisms to be as high as 4.6%. It should be noted that none of these patients were symptomatic, and these were incidental findings on a routine chest CT obtained for malignancy monitoring.

Cement leakage during pedicle screw placement has been reported to be up to 17% with no clinical significance [34]. Kim et al. [64] investigated the benefits and drawbacks of cement augmentation of standard and fenestrated pedicle screws. They discovered a 4.8% leakage rate in the standard screw group and a 9.3% leakage rate in the fenestrated screw group, with no complications associated with this extravasation.

Revising a cement-augmented PSI construct can present great difficulty. Concerns that removing a cemented PSI would compromise the pedicle and cause vertebral destruction, preventing revision instrumentation, are unfounded. Biomechanical studies on cadaveric specimens have shown that this risk is minimal, and cemented screws can be re-instrumented while the screw tract remains intact [65]. Bullmann et al. [66] conducted a cadaveric study comparing the strength of the cemented versus standard screws in revision cases. They discovered none of their vertebrae fractured with the removal of cemented screws, and that re-instrumentation with the cement provided a more robust fixation than standard screws. Another study by Martín-Fernández et al. [67] retrospectively documented complications associated with screw cement augmentation. Only two of the 313 patients examined required removal due to chronic infection. These screws were removed and re-instrumented with 1 mm larger diameter screws without incident, and the PMMA was left in place and not re-cemented. No pullout was observed in any of their screws.

Overall, when done correctly, and with attention to detail, cement augmentation is a safe and effective method of increasing construct stability.

Conclusions

The advancement in pedicle screw augmentation, which combines traditional vertebroplasty techniques with PSI, has expanded indications with favorable clinical outcomes. Cement augmentation began in general orthopedics to help with implant stability for joint replacements. Cement use has since progressed to become a standard of care in spine surgery for the surgical treatment of compression fractures, as well as to increase the stability of spinal implants. Various cement materials and instrumentation types have been used with excellent results improving construct stability and pullout strength in cases of decreased BMD. Biomechanical studies continue to show increased pullout strength, and clinical data consistently shows safety with a very low complication rate. This procedure can be performed safely and effectively with current techniques and it is a modality that every spine surgeon should consider implementing to improve fixation when indicated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Laurence E Mermelstein for providing Fig. 3.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: PB, TM, SER, AM; data curation: PB, TM, SER, AM; formal analysis: PB, TM, SER, AM; funding acquisition: PB, TM, SER, AM; methodology: PB, TM, SER, AM; project administration: PB, TM, SER, AM; visualization: PB, TM, SER, AM; writing–original draft: PB, TM, SER, AM; writing–review & editing: PB, TM, SER, AM; and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.