|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 17(3); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Study Design

Validation of a novel retrospective comparative questionnaire to obtain post-intervention outcome data in patients with lumbar degenerative spinal disease.

Purpose

Acquiring prospective outcome data for spinal intervention is not frequently feasible in resource-depleted units in certain developing countries. Therefore, a novel retrospective instrument is being validated for clinical use, which can act as a standard method to describe outcomes when data are retrospectively collected.

Overview of Literature

The standard method of collecting outcome data after a spinal intervention has been prospective, including the Oswestry Disability Index, Roland-Morris Questionnaire, and Short Form-36. The process of content validation and reliability of the novel retrospective spinal questionnaires is highlighted.

Methods

Questionnaire items were created based on a literature review, followed by a process of content validation by experts and modification based on expert opinions to achieve an acceptable content validity index (CVI, 0.70ŌĆō1.00). To calculate factor loadings for each question, a pilot test was subsequently conducted from a pool of patients who underwent lumbar spine surgeries for degenerative spine diseases.

Results

All items achieved a CVI of >0.85 for both relevancy and clarity and were successfully validated after appropriate corrections were made before the second validation phase. Except for Q9 and Q10, which showed low-loading factors in the pooled sample, the remainder of the items had acceptable loading factors across different subgroups, indicating that the passage of time did not affect the results of the exploratory factor analysis.

Conclusions

The retrospective questionnaire that encompasses the general well-being and lumbar-specific symptoms is a valid and reliable instrument to provide an impression of the outcome after intervention in a patient with a degenerative lumbar spinal disease. A summative score will indicate the overall outcome.

Research concerning degenerative spinal disorders relies on the patientŌĆÖs perspective of their quality of life (QOL) to assess treatment effects [1]. Multiple questionnaires were available in the field, which evaluated their spine-related disability index, including the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) [2], Roland-Morris Questionnaire (RMQ) [3], and Quebec classification score [4], whereas other questionnaires were used to assess the patientŌĆÖs QOL, such as Short Form-36 (SF-36) [5] and EuroQoL 5-Dimension questionnaires [6]. These are comprehensive questionnaires that serve as a reliable tool to gage patientsŌĆÖ specific and general functional state, at one point in time; considering the symptoms and their effects on daily activities and QOL. If this assessment is repeated at various timelines, it can be used to assess the response to a specific therapeutic modality.

Various outcome instruments are available, and the researcher determines the most appropriate instrument [7]. To assess the progress of the condition or response to treatment, commonly used questionnaires, including ODI [2], RMQ [3], and SF-36 [5], require prospectively recorded data at various points. As it is time-consuming, infrastructure and manpower would be required to conduct such research. In several parts of the developing world, this sort of facility and support is lacking; even if it were occasionally available in a busy clinical practice, such evaluation could not be performed on every patient.

Lumbar degenerative disease is a common disorder. A cohort of patients would benefit from surgical intervention. The surgical options for degenerative spinal disorders are varied, ranging from simple neural decompression using a microscope or endoscope to more intricate approaches involving fusion surgery. The surgical options that the surgeon advocates are based on their training, experience, and locality. To date, the literature on this topic is predominantly from developed countries. The surgical strategies employed in the developed world to manage lumbar degenerative disease may differ in developing or less developed countries. There is a paucity of literature on the techniques used and the outcomes regarding degenerative spinal disease in the developing world. Owing to its limited resources, these countries tend to practice a more basic neural decompression surgery rather than fusion surgery. However, owing to the limitation in obtaining prospective data in these countries due to various reasons, including the lack of funding, heavy clinic load, logistics, and manpower, these outcome data are not widely available. Therefore, these data sets do not get into mainstream literature but are possibly presented only in local meetings in the format of the surgeonsŌĆÖ experience. We devised a truncated questionnaire that permits a broader retrospective and comparative evaluation of general well-being and spine-specific disabilities for patients with a lumbar degenerative spinal disorder who have had an intervention to capture the outcome data from this cohort of patients. The outcome measures would permit the researcher to appraise the benefit of a particular intervention regarding functional domains.

The questionnaire has the following two large domains: general well-being and the lumbar-specific spinal disability index. Each domain has five questions, and the responses are objective with either one of three to four responses. The choice of questions in each domain is general (pain intensity, personal care, sleeping, social life engagement/recreation, and work) and specific (walking, sitting, change in position, bladder dysfunction, and lower limb numbness). These parameters were chosen to reflect a more holistic appraisal of the functional state despite being a short questionnaire. This assessment can be retrospectively performed either in person or through the telephone, which brings out the advantages of a greater response rate, relatively inexpensive but quick data collection, and the ability for interviewers to probe for incomplete or ambiguous answers [8]. Furthermore, this method is relevant in the current pandemic situation. We are presenting our assessment tool and the validation process.

Content validation certifies whether an instrument measures what is intended and verifies whether the items properly reflect the content domain of interest and whether the scale dimensions are consistent with each proposed item and provide clarity to respondents [9,10]. Content validity aspects include the relevance of the item and its clarity, which are determined by an evaluation of the instrument items by a group of experts with previous experience or currently recognized in the field of study, such as practicing surgeons, physicians, or experts [11]. This study aims to validate the content of a developed instrument to assess the general well-being and QOL of individuals with lumbar degenerative diseases who underwent lumbar spine surgeries (intervention).

The development and validation of an instrument encompass the following five distinct phases: planning, construction, quantitative analysis, validation, and a pilot study among patients [11]. The instrument planning and construction phases comprised an extensive literature review and expert opinions. Content validation and the pilot study are described in the present study. This project was approved according to protocol number 2020819-8994 of the Medical Research Ethics Committee of University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur. Informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Content validation (phase I) was performed in two rounds. In the first round, the instrument was initially subjected to content validation by a committee of 20 medical experts with interest in the field of degenerative spinal disease. The content validation questionnaire was developed in English and was evaluated for the relevance and clarity of each item developed. The second round of content validation was repeated among 15 experts after the initial responses and comments were considered and relevant changes made to fine-tune the instruments. Once the content validations by the experts were concluded, a pilot study was conducted to evaluate the construct validity. A flow chart in the development of a new questionnaire is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Based on the protocol described by Polit et al. [12], we chose 20 medical practitioners, including neurosurgeons, orthopedic spine surgeons, rheumatologists, neuropsychologists, and rehabilitation physicians with experience in the care of patients with a lumbar degenerative disease, to participate. These included both local and foreign medical practitioners. The length of experience of the experts ranged from 8 to 25 years. In the first round of content validation, 20 experts with seventeen local Malaysian experts and three international experts responded within a specified period, whereas fifteen experts from a similar cohort participated in the second round.

A pilot study was conducted on a pool of patients who underwent lumbar spine surgeries for degenerative spine diseases in a tertiary hospital in Kuala Lumpur from January 2008 to December 2019. A total of 104 patients were successfully contacted and interviewed via telephone within 2 weeks. According to Gorsuch [13] in 1983, the minimum sample size for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) should be at least 100. Therefore, the collected data (n=104) were adequate to calculate factor loadings for each question.

The content validity of the developed instrument was statistically analyzed using a content validity index (CVI). To calculate the CVI, each item was ranked on a 4-point scale (1=not relevant, 2=somewhat relevant, 3=quite relevant, and 4=highly relevant). For each item, the CVI was calculated as the number of experts who provided a rank of 3 or 4, divided by the total number of experts. The kappa modified coefficient was used to determine the degree of relevance agreement of the CVI and was calculated according to protocols set by Polit et al. [12]. Twenty experts participated in the first phase of content validation; the acceptable CVI value for each item was 1.00ŌĆō0.70, and the kappa modified value was 1.00ŌĆō0.68. Since fifteen experts participated in the second phase, the acceptable items were those with a CVI ranging from 1.00 to 0.80 and a kappa modified value ranging from 1.00 to 0.80. The CVI considered the number of experts consulted for each phase; the difference in the number of experts in the different content validation phases of the present study did not influence the statistical results.

To construct the validity of the questionnaire, first, the pilot study data was analyzed through parallel analysis (PA), which is a Monte Carlo simulation method that helps scholars define the number of factors to retain in the principal component and EFA. This technique delivers a superior difference to other techniques that are generally used for the same purpose, such as the scree test or the KaiserŌĆÖs eigenvalue-greater-than-one rule. In this study, PA was performed based on this method using online software for PA (www.statatoddo.com). PA is a method used to define the number of factors in factor analysis. The following factors affect PA results: the choice of the eigenvalue percentile, strength of the factor loadings, number of variables, and sample size of the study. Following PA, EFA was applied to evaluate the construct validity and determine the contribution of each item (loading factor) to related components (factor). EFA was performed using varimax rotation to determine the factor structure among 10 items related to the scale. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

In the first round of content validation, the domains were considered satisfactory (CVI between 0.70 and 1.00) for evaluating the general disability and the region-specific domains. As shown in Table 1, all items in the General Characteristics Domain obtained satisfactory scores; therefore, all the items in this domain were maintained in the second version of the instrument. Item 3, which assessed sleeping although achieved acceptable scores in relevancy (CVI=0.75, kappa=0.746) and clarity (CVI=0.70, kappa=0.746), was modified to ascertain whether the sleeping problems were due to spinal problems instead of other issues as pointed out by one of the experts. Moreover, the items that assessed pain intensity, social life engagement, and recreation had their wordings changed for improved understanding; for example, in the pain intensity section, the options of ŌĆ£improved, maintained, and worsenedŌĆØ were changed to ŌĆ£reduced, persistent, and worsened.ŌĆØ Items 6ŌĆō10 presented the common scores of the lumbar-specific items. All items achieved a CVI of >0.85, except for relevancies in item 8, which assessed the change in positions of patients (CVI=0.75), and clarity in item 9 patientŌĆÖs bladder dysfunction (CVI=0.75). To keep the questions more focused and maintain clarity to obtain a consistent understanding of the question either by reading or listening to the question by the respondent, we added the phrase ŌĆ£After the spinal intervention, ŌĆ”ŌĆØ to each of the questions. Moreover, wordings were improved while the experts highlighted some grammatical errors to keep the questions all in the present tense.

The content validation of the general disability and lumbar-specific domains in the second round of the content validation process is presented in Table 2. The second version of the instrument was resubmitted to a similar expert committee for re-evaluation of all items. Fifteen experts responded and participated in the second phase of content validation. All items achieved a CVI of >0.85 for relevancy and clarity. Thus, all items were successfully validated after appropriate corrections were made before the second validation phase.

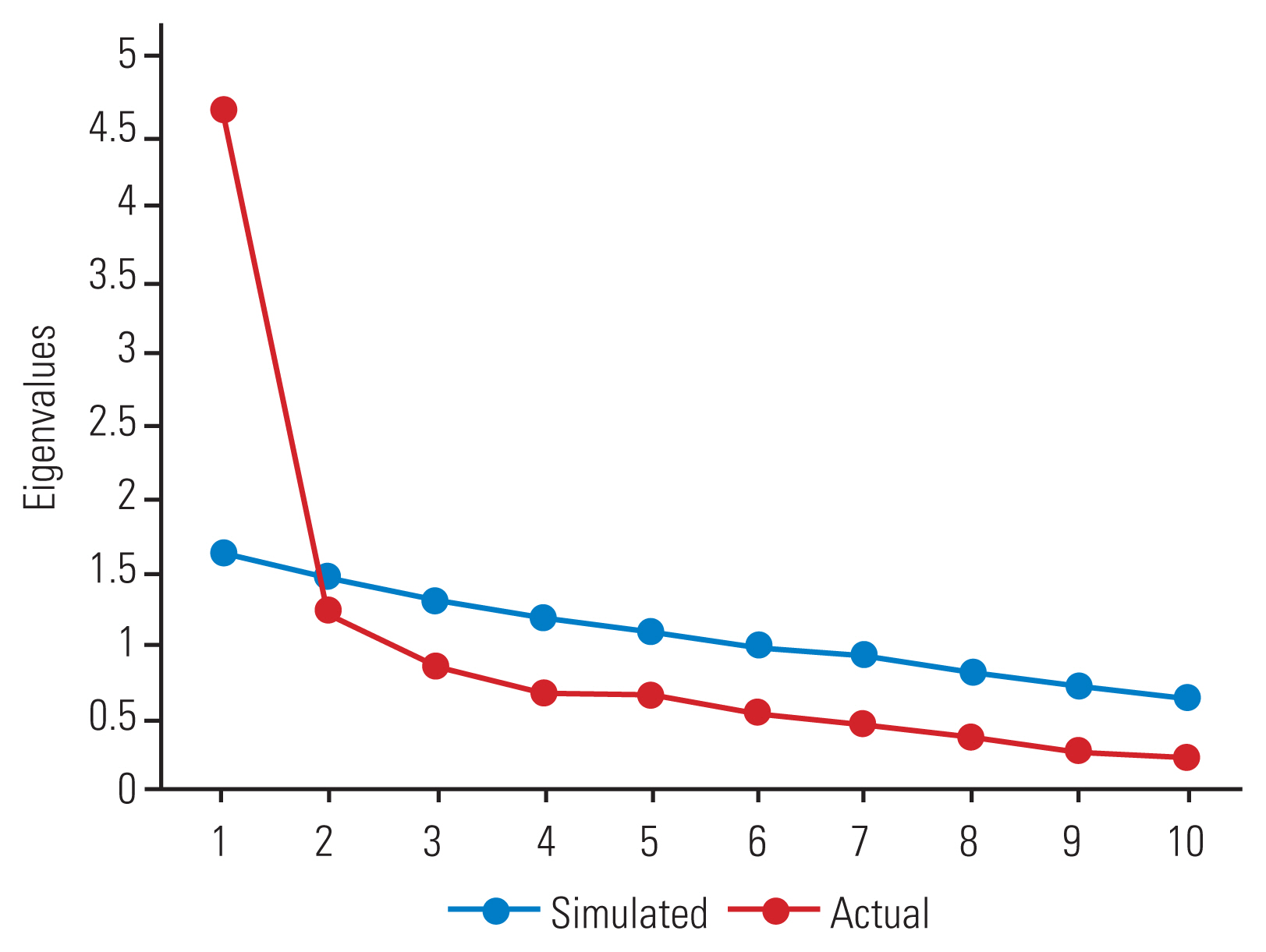

In this section, the PA results are presented for the adapted instrument, including 10 items. The PA indicated that only the eigenvalue of the first extracted factor was more than the eigenvalue of simulated data (╬╗=1.646), suggesting that a single factor can be extracted from the data; therefore, in the next step for EFA, the number of extracted components is considered as one factor (Fig. 2).

EFA using varimax rotation was applied to determine the factor structure among 10 items related to the general well-being scale. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.863, which was above the suggested value of 0.6, and BartlettŌĆÖs test of sphericity was significant (Žć2[45]=420.581, p<0.05).

In the current study, all initial communalities were above the threshold. The results of EFA on all 10 items were forced into one component based on the PA results. The results showed that this component explained 46.6% of the variance. According to these results, as shown in Table 3, all items showed a loading factor of above 0.5, except items 9 and 10, which had a loading factor of <0.5.

To investigate the effect of time on the outcomes of construct validity, the sample was divided into four categories, and EFA was performed on each subset of data because the current study is based on a retrospective study that took place from 2008 to 2020 (Table 4). The results revealed that, except for Q9 and Q10, which had low-loading factors in the pooled sample, the remainder of the items had acceptable loading factors across different subgroups, indicating that the passage of time did not affect the EFA results.

Lumbar degenerative spinal disease is a ŌĆ£wear and tearŌĆØ condition that affects the more mobile parts of the spine, mainly the cervical and lumbar regions [14]. Most patients manifest symptoms of pain or numbness as their primary problem. The threshold to offer surgical intervention also hinges on the severity of the symptoms leading to functional disability in executing the activities of daily living and the QOL in terms of vocation and recreation. Therefore, the success of a particular intervention rendered to a patient with a degenerative spinal disease can be gauged by assessing the resolution or improvement of the presenting symptoms [15], wherein a return to the normal or usual QOL for a given age and medical condition is the ideal outcome of treatment [16]. This provides a good indicator of the functional benefit that the patient had derived from a particular intervention/treatment within his environment. Therefore, in cases of degenerative lumbar spinal diseases, symptomatology and functional disability play a key role in making management decisions and assessing the outcomes of these patients before and after the intervention.

Wilson and Cleary [17] proposed a taxonomy for different health outcome measures, which divides these outcomes into the following five levels: biological and physiological factors, symptoms, functioning, general health perceptions, and overall QOL. Consequently, various forms of lumbar spine-specific and general well-being questionnaires have been used to this end [2ŌĆō4]. However, the key features of these questionnaires are that they are conducted in a prospective manner, indicating the symptoms and functional disability at that one point in time. Some of these lengthy questionnaires have multiple stems for one particular symptom that is being assessed, such as the ODI [2]; consequently, it can extract finer details of a symptom or activity. Although it is a more detailed assessment tool for acquiring these data in real-time from the participants, it needs patientsŌĆÖ cooperation and compliance. These questionnaires have undergone vigorous validation and are a standard means of furnishing outcome data for degenerative spinal disorders in several works of literature.

Given the busy service and lack of research assistants, prospective functional data are not routinely collected for most degenerative spinal disease cases that sought treatment in our facility. Based on the clinical follow-up, it is apparent that most of the patients who have undergone surgical intervention seem to have improved in functional ability. We wanted to study our surgical outcomes more scientifically; however, we realized that we lacked the prospective data. This initiated us to devise an assessment tool to perform a retrospective comparative assessment in a more standardized manner to allow a more systematic assessment of the outcome. The retrospective assessment tool will allow a comparison of the perceived degree of improvement in symptoms before and after the intervention. This comparison can be made at the various timelines of the intervention. However, the further the timeline is from the index surgery, there is the possibility that the patient may not be able to make a reliable comparison. Subsequently, we keep the questions more functional regarding their overall experience in a particular item of assessment rather than asking the patient to score the specific symptoms in a retrospective manner to minimize this sort of bias. Scoring symptoms retrospectively may be full of errors. However, evaluating the patientŌĆÖs change experience in various functional items after an intervention in a broader sense rather than specific scoring would minimize the errors in terms of recall biasness. Without a retrospective instrument, we cannot measure the result more objectively in a standardized manner due to the lack of prospective functional data.

An obvious limitation of these existing questionnaires, including the ODI, RMQ, and SF-36, is that the data must be prospectively collected at two different time points, such as before and after the intervention, to compare the outcome after a particular intervention. This would be a more sensitive and specific way of presenting the outcome data; however, obtaining such data would require resources and patient commitment to answer these detailed questionnaires. To achieve a similar endpoint of outcome assessment after a particular intervention in a patient with a degenerative spinal disease, we have validated a single assessment tool using a comparative questionnaire to gage the difference the patient experienced after the intervention. The questionnaire examines a few common functional parameters to surrogate the patientŌĆÖs overall functional ability. Since the answers expected are more of a reflection of the difference that the patient experiences after the intervention, the questions do not interrogate details of the symptom or activities like the ODI. Therefore, the options within each parameter are kept broader although distinct (Appendix 1). This assessment tool is more usable despite losing on the finer symptomatology and functional analysis. By indicating the usefulness of certain interventions in patients with a lumbar degenerative disease, particularly in resource-limited countries, this assessment tool can derive reasonable outcome assessments.

The questionnaire underwent content validation and reliability tests. Factor loadings are correlation coefficients between observed variables and latent common factors [18]. Factor loadings are part of the outcome of factor analysis, which serves as a data reduction method designed to explain the correlations between observed variables using a smaller number of factors. A factor loading that falls outside the interval bounded by (┬▒cutoff value) is large and thus retained. Conversely, a factor loading that does not meet the criterion indicates that the corresponding observed variable should not load on the corresponding common factor.

Pain intensity, personal care, sleeping, social life engagement/recreation, and work were the general well-being domains that we focused on. The first question was about pain intensity. To encompass the overall pain and not specific to low back pain and lower limb pain, we kept this question broad. We assessed the overall pain syndrome related to the degenerative spinal disorder and hoped that the secondary pain-related issues will resolve or diminish by tackling the primary pain source. However, there were limitations to this question, as addressed by the experts, wherein patients would occasionally confuse non-spine-related pain simultaneously, resulting in differing expected results. However, this question has a factor loading of 0.776, which makes it a strong indicator that this question is highly important to assess the patientŌĆÖs general well-being outcome. The second question included in the questionnaire was about personal care and activity of daily living (ADL). Options with concepts of being fully ADL independent, partially dependent, and total dependent were implemented in this section. Like the first question, we recognize that there may be other factors affecting ADL independence apart from the spine issue. This question has a factor loading of 0.700, which makes it a relatively strong contributor to a patientŌĆÖs QOL.

As the following functions had specific relation to the lumbar spine, walking, sitting, changing position, bladder dysfunction, and lower limb numbness were the lumbar spine-specific domains that we focused on. For example, in the first question, which focuses on walking, we emphasized any presence of back or leg pain and if it causes any restriction in walking as a result of the back pain. This question has an acceptable factor loading of 0.796. The domains of bladder dysfunction (0.396) and lower limb numbness (0.390) were the only two items that had a factor loading of <0.400. This could be explained as the incidence of bladder dysfunction due to the degenerative spine disease was relatively uncommon even before surgery in our pool of patients (14.4%), thereby making this question irrelevant in most of the patients in the pool. Meanwhile, in the domain of lower limb numbness, patients may perceive numbness in different ways; while some patients felt the residual numbness was acceptable and negligible, some still felt that the numbness in the lower limbs affected their daily activities. Most studies considered loading factors of >0.5 and any lower than that should be excluded and removed from the questionnaire. However, according to [18ŌĆō20], the cutoff value is arbitrarily selected depending on the field of study, and (┬▒0.4) seems to be preferred by several researchers. Therefore, as the values of questions 9 and 10 were close to the cutoff point of 0.4, it is not excluded in the current study. However, to determine their value and decide on whether these two items should be excluded in the future, further evaluation should be made in future studies.

The intervention and assessment dates are recorded in the questionnaire to determine the timeline. The same instrument can be used to record outcome measures at various timelines. Therefore, analyzing the benefit of that index intervention at various time points is important. The confounding factors that would affect the outcome apart from the intervention would have a similar effect on the participantŌĆÖs assessment of symptomatology in both the prospective and retrospective questionnaire should be taken into account.

To obtain an overall impression of the outcome after an intervention, the outcome for each item in the questionnaire has been denoted a score. We propose a summative score for the general well-being index and lumbar-specific disability index, respectively. A scale is used, wherein the general well-being index can be scored from 5 to 16, and the lumbar-specific disability index, which can be scored from 5 to 15. These scores are summated and subsequently grouped randomly into four categories to indicate the overall outcome (excellent, good, moderate, and poor) (Appendix 2). Once in clinical use, further clinical data will be employed to evaluate the discriminative and predictive validity as well as optimize the cutoff point for the scale.

This study had some limitations inherent to a retrospective questionnaire assessing functional outcomes. One of the key elements is the ability to remember the severity of the symptomatology at presentation. The risk of this biasness has been alleviated by focusing on the experiential change as perceived by the participant of the symptoms in functional terms rather than grading the severity of the symptom at presentation in a retrospective manner. The analysis of the effect of time on the outcomes of construct validity indicated that the passage of time did not affect the results of the EFA (Table 4). The formulation of a generic retrospective clinical symptomatology questionnaire for a lumbar degenerative disease has to encompass most of the common symptoms of that condition. However, not all the participants will suffer from all those symptoms. This is one of the limitations of a questionnaire-based assessment. Nevertheless, in this novel retrospective instrument, the absence of the symptom that is being assessed before and after the intervention would not have a negative impact on the outcome. However, if the patient develops a new symptom that was not present before the intervention, this will result in a worse outcome score. Another limitation inherent to a questionnaire-based functional assessment is the inability to tease other co-existing contributory medical conditions, such as knee osteoarthritis and peripheral neuropathy, which may also have relevance to the symptoms that are being assessed, which may impact the outcome assessment. However, this limitation exists in both prospective and retrospective disease-specific outcome assessments performed using a questionnaire [2,4]. However, further research that considers the premorbid history and medical characteristics, as well as their temporal relationship as potential confounders in determining the lumbar-specific disability outcomes, can be conducted. This is a novel instrument to permit a more standardized means of measuring outcomes for the cohort of patients with a lumbar degenerative disease who do not have prospective clinical data. More developing countries would be able to describe the outcomes in reference to the time of intervention of various sorts of treatments that were performed for patients with a lumbar degenerative disease using such instrument.

The content validation of the general well-being index post-intervention for spinal disorders and post-intervention lumbar-specific spinal disability index shows that it is a valid and reliable instrument to provide an impression of the outcomes following an intervention in a patient with a degenerative lumbar spinal disease. The functional parameters that were gauged were relevant to the disease condition. This tool will afford a standardized means of performing the retrospective comparative assessment of the effectiveness of a particular intervention. This is a valuable tool to describe outcome measures in a cohort of patients who do not have prospective pre-intervention data.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. The questionnaire has been copyrighted by the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: SYC, MD, DG; data curation: SYC ; formal analysis: SYC; funding acquisition: none; methodology: MD; project administration: none; visualization: DG; writingŌĆōoriginal draft: SYC, MD, DG; writingŌĆōreview and editing: all authors; and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Table┬Ā1

The first phase of content validation of the general disability domain and lumbar specific disability domain

Table┬Ā2

The second phase of content validation of the general disability domain and lumbar specific disability domain

Table┬Ā3

Factor loadings based principal component analysis with varimax rotation for 10 items related to the general well-being scale

| Items | Factor loading |

|---|---|

| Q5 | 0.844 |

| Q6 | 0.796 |

| Q1 | 0.776 |

| Q8 | 0.768 |

| Q4 | 0.764 |

| Q2 | 0.700 |

| Q3 | 0.660 |

| Q7 | 0.552 |

| Q9 | 0.396 |

| Q10 | 0.390 |

Table┬Ā4

Exploratory factor analysis based on time (loading factors)

References

1. Copay AG, Glassman SD, Subach BR, Berven S, Schuler TC, Carreon LY. Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry Disability Index, Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36, and pain scales. Spine J 2008;8:968ŌĆō74.

2. Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, OŌĆÖBrien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980;66:271ŌĆō3.

4. Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, et al. The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale: measurement properties. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:341ŌĆō52.

5. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473ŌĆō83.

6. EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199ŌĆō208.

7. Poolman RW, Swiontkowski MF, Fairbank JC, Schemitsch EH, Sprague S, de Vet HC. Outcome instruments: rationale for their use. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91(Suppl 3): 41ŌĆō9.

9. Benson J, Clark F. A guide for instrument development and validation. Am J Occup Ther 1982;36:789ŌĆō800.

11. Natalio MA, Faria CD, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Michaelsen SM. Content validation of a clinical assessment instrument for stair ascent and descent in individuals with hemiparesis. Braz J Phys Ther 2014;18:353ŌĆō63.

12. Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity?: appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:459ŌĆō67.

13. Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): L. Erlbaum Associates; 1983.

14. Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, Murtagh FR, Gabriel Rothman SL, Sze GK. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1448ŌĆō65.

16. Silver GA. Paul Anthony Lembcke, MD, MPH: a pioneer in medical care evaluation. Am J Public Health 1990;80:342ŌĆō8.

17. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: a conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995;273:59ŌĆō65.

18. Michalos AC. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014.

19. Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol Bull 1988;103:265ŌĆō75.

20. Pituch KA, Stevens JP. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: analyses with SAS and IBMŌĆÖs SPSS. 6th ed. New York (NY): Routledge; 2016.

Appendices

Appendix┬Ā1

Assessment tool

Appendix┬Ā2

Scoring

University of Malaya general well-being index post-intervention for spinal disorders

| Items | Score |

|---|---|

| Pain intensity | |

| Personal care | |

| Sleeping | |

| Social life | |

| Work | |

| Total score (scale: 5ŌĆō16 points) |

- TOOLS