|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 13(6); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the association of surgical intervention with clinical and quality of life (QoL) outcomes in patients who underwent posterior spinal surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) with spinal calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition (SCPPD) versus that in those who underwent the surgery for LSS without SCPPD.

Overview of Literature

Calcium pyrophosphate (CPP)-associated arthritis is one of the most common types of arthritis. The clinical outcomes are well studied in CPP-associated arthritis of the appendicular joints. However, few studies have investigated SCPPD.

Methods

A single-institution database was reviewed. LSS patients were categorized as those who did and did not have SCPPD, based on histologic identification. Clinical presentations and postoperative results were analyzed. Disability and QoL were assessed using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey.

Results

Thirty-four patients were enrolled, with 18 patients being allocated to the SCPPD group and 16 being allocated to the non- SCPPD group. Preoperative and postoperative pain scores were not significantly different between the groups (p=0.33 and p=0.48, respectively). The average preoperative ODI score in the SCPPD group was slightly higher than that in the non-SCPPD group (57 vs. 51, p=0.33); however, the postoperative ODI score was significantly lower (15 vs. 43, p=0.01). The postoperative physical function, vitality, and mental health of the SCPPD patients were also significantly improved (p=0.03, p=0.022, and p=0.022, respectively).

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition (CPPD) or pseudogout is the third most common type of inflammatory arthritis. As compared to osteoarthritis, CPPD is associated with higher levels of inflammation, pain, stiffness, and functional limitation [1]. Induced inflammation is associated with pain, stiffness, and functional limitation in the affected joints. CPPD of the spine is a rare disease. CPPD in the lumbar area of the spinal structure (SCPPD) can be found in the intervertebral disc (Fig. 1) [2], disk fibrocartilage [3], ligamentum flavum [4,5], and facet joint [6-8]. The prevalence varies as per the spinal structure that is affected. Berlemann et al. [2] reported incidental CPPD in 12.6% of lumbar intervertebral discs. Yayama et al. [4] identified CPPD in 36.66% of ligamentum flavum samples, and Markiewitz et al. [5] reported CPPD in the ligamentum flavum in 24.5% of surgically treated patients. Inflammation in these structures may cause pain in the affected area as well as neuropathic pain that may be attributable to inflamed neural structures or compressive effect of the inflamed tissues. Common clinical presentations include back pain and/or radiating leg pain [6,8] that may mimic infection, cauda equina syndrome [9], spinal epidural hematoma [10], and spinal stenosis [11-14]. However, the clinical significance of SCPPD in patients who present with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) remains unclear. We hypothesized that posterior spinal surgery to correct LSS should increase inflammation in SCPPD patients as compared to that in non-SCPPD patients and that total removal of these structures may be necessary. We further hypothesized that different levels of inflammation and pathology in the two conditions would result in dissimilar pain levels and clinical outcomes. However, as per our literature review, no studies have validated these hypotheses. Thus, we aimed to study the effects of SCPPD in LSS patients.

This study aimed to investigate the association of surgical intervention with the clinical and quality of life (QoL) outcomes in patients who underwent posterior spinal surgery for LSS with SCPPD versus that in those who underwent the surgery for LSS without SCPPD.

This study was conducted at a university-based tertiary referral center. The protocol for this study was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University (IRB approval no., Si233/2014).

A single-institution database was reviewed, identifying LSS patients who were surgically treated with posterior spinal surgery during the 2003–2011 study period. All the LSS patients were categorized as those with and without SCPPD. Definite diagnosis of SCPPD was confirmed using histologic identification of calcium pyrophosphate (CPP). Clinical presentations, complications, and postoperative results of both the groups were analyzed.

SCPPD patients who underwent decompressive laminectomy and/or fusion were included after histopathologic diagnosis. Non-SCPPD patients were then matched using demographic data. Patients were excluded if their medical chart contained incomplete data and/or the follow-up period was <2 years.

All the patients underwent decompressive laminectomy with or without discectomy as per the clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings (Fig. 2). No patient underwent total removal of CPP-involved tissues or steroid injection (adequate decompression was confirmed in all cases without total facetectomy or total discectomy). Spinal fusion with or without instrumentation was performed if the patient had significant back pain or instability. Ligamentum flavum, facet capsule, and disc specimens were sent for histopathologic examination for all patients. The enrolled patients were divided into the following two groups: SCPPD group (18/34) and non-SCPPD group (16/34) as per the histopathologic report. Patients in the SCPPD group did not receive colchicine postoperatively.

Data were collected via chart abstraction; demographic data, clinical presentations, operative data, radiographic findings, and postoperative data were recorded. Pain was evaluated using the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) (range, 0–10). All the patients completed the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) version 2.0 questionnaire (Thai version) [15] and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) low back pain version 1.0 questionnaire (Thai version) [16] before the surgery and at the last follow-up. Informed consent was obtained from all patients at the last followup. Fusion was evaluated using plain radiographs.

Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, and range values, were calculated for quantitative data, while frequencies were calculated for categorical and ordinal variables. Mann-Whitney U-test and chi-square test were used to compare continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistics ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Thirty-four patients (15 men and 19 women) were enrolled, with 18 patients allocated to the SCPPD group and 16 to the non-SCPPD group. Demographic, clinical, and operative data are shown in Table 1. The mean operative time and mean intraoperative blood loss were not significantly different between the groups. The mean follow-up duration was 61.9 months (range, 41–92 months).

The demographic data of the groups were comparable; however, the mean body mass index (BMI) of the SCPPD group was significantly lower than that of the non-SCPPD group (23.56 kg/m2 versus 26.47 kg/m2, p=0.015). The commonly affected levels in both the groups were L4–5, L3–4, and L5–S1. No patient had a history of CPPD in other joints. Fourteen of the 18 SCPPD patients and 11 of the 16 non-SCPPD patients underwent spinal fusion. None of these patients required additional surgery because of nonunion or surgical complications.

Preoperative and postoperative pain scores were not significantly different between the groups (p=0.33 and p=0.48, respectively). The average preoperative ODI score in the SCPPD group was slightly higher than that in the non-SCPPD group (57 versus 51, p=0.33); however, the postoperative score was significantly lower (15 versus 43, p=0.01). Physical function, vitality, and mental health were also significantly improved in the SCPPD group at the last follow-up (p=0.03, p=0.022, and p=0.022, respectively). Regarding other items and summary scores, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups. Preoperative and postoperative VRS, ODI, and SF-36 data are shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in the postoperative scores among the three operative procedures. Subgroup analysis of the SCPPD group for each operative procedure is presented in Table 3; no significant differences were detected among the three surgical procedures.

The present study revealed that SCPPD group patients had a significantly higher average age than the non-SCPPD group patients. SCPPD group patients also had higher levels of back pain than the non-SCPPD group patients; however, the difference in the pain levels of the groups was not statistically significant. Preoperative pain score, percentage of back pain, ODI, and SF-36 score were not significantly different between the groups, although the SCPPD group patients had a significantly lower BMI. This finding may indicate that inflammation in CPP-involved tissue plays the role. The most common affected levels were L4–5 and L3–4 in both the groups. Markiewitz et al. [5] reported that SCPPD patients had more acute symptoms with similar clinical presentation. No pathognomonic sign of SCPPD has been reported in the literature. Although facet cyst is reportedly associated with SCPPD, we found that the incidence of facet cyst was comparable in the two groups.

Very few studies have described the surgical treatment in SCPPD patients. Mahmud et al. [17] reported successful relief of symptoms in SCPPD patients after surgical decompression and/or fusion. However, to our knowledge, no study has reported any comparison between SCPPD and non-SCPPD in LSS. The authors hypothesized that surgical intervention would result in more inflammation in patients with LSS and SCPPD who already had more inflammatory features than LSS patients without SCPPD. The present study revealed comparable pain and overall QoL in the groups after the surgical treatment, although total removal of CPP-involved tissues was not performed for any patient. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of preoperative disability, pain, and QoL. Although the SCPPD group patients showed significantly better postoperative clinical results for disability, physical function, vitality, and mental health, there was no significant difference between the groups for overall physical and mental health at the last follow-up. Operative procedures (i.e., fusion and instrumentation) may not correlate with postoperative function because the subgroup analysis did not detect any significant differences among the three surgical procedures. This may be attributable to selection bias. The authors conclude that total removal of CPP-involved tissues is not mandatory, given that all SCPPD group patients demonstrated significant improvement in pain, ODI, and SF-36 QoL scores. Limitations of this study included the fact that it was a single-center retrospective study and involved a relatively small number of participants. In this study, we determined fusion using plain radiographs. Computed tomography scan would have been more accurate for evaluating fusion. A large, prospective multi-center study may be able to obtain additional information on the clinical impact of SCPPD in degenerative spine disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of CPPD on clinical and QoL outcomes in surgically treated LSS patients. Surgical intervention resulted in good clinical outcomes in SCPPD patients. As per our findings, total removal of CPP-involved tissue is not necessary for outcome improvement. Thus, surgery should be performed as indicated based on the clinical presentation without considering the presence of CPPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge professor Thossart Harnroongroj for assistance with manuscript development, Miss Natnicha Sriburiruk, Miss Siranart Kumpravat, and Miss Julaporn Pooliam for assistance with statistical analysis.

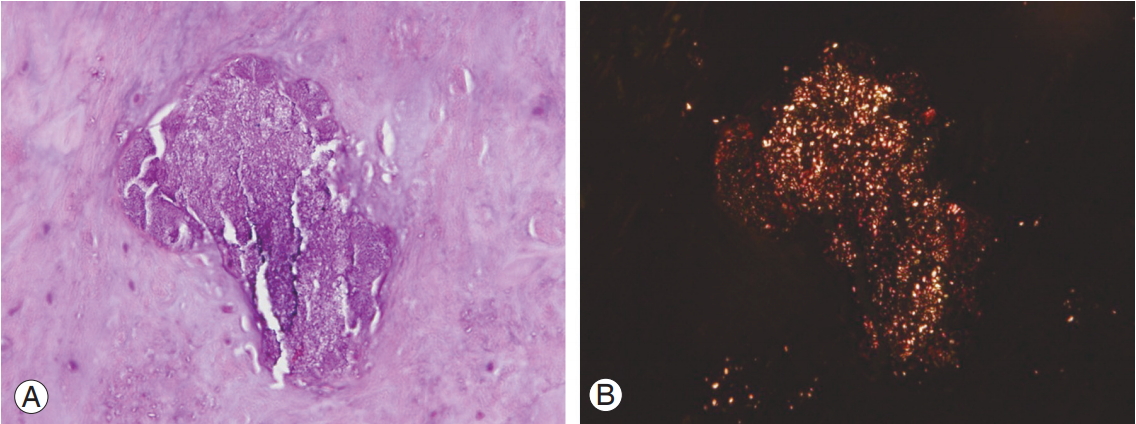

Fig. 1.

(A) Intervertebral disc (H&E staining, ×400) shows minimal calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition (purple staining material in the center). (B) The purple staining material shows rhomboid-shaped crystals on polarized light.

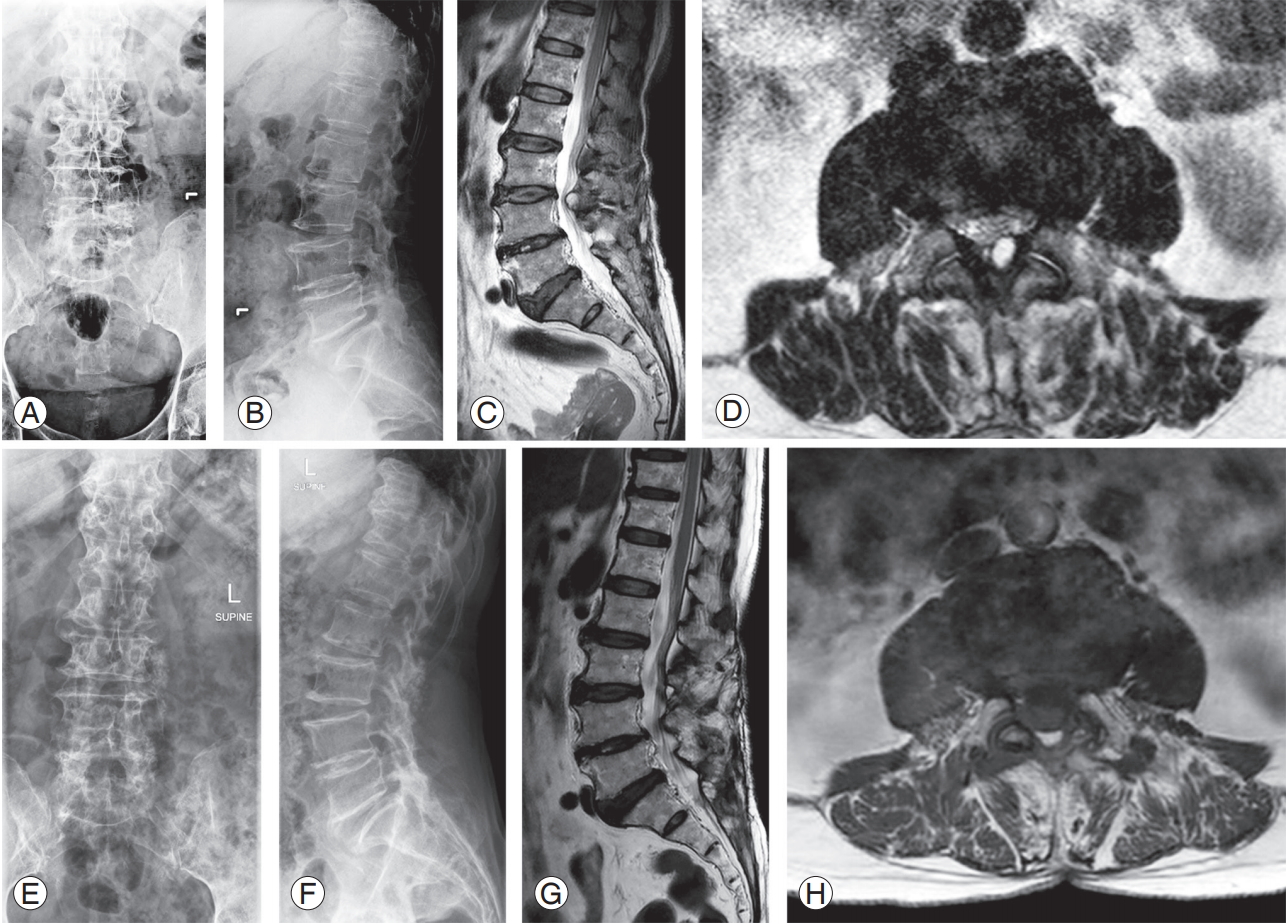

Fig. 2.

(A–D) demonstrated preoperative plain radiograph and T2-weighted MRI of 67-year-old woman who had severe back pain with bilateral radicular pain, underwent laminectomy and uninstrumented posterolateral fusion. (D) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showed cystic mass originated from ligamentum flavum without calcification at L3–4 level. (E–H) Postoperative plain radiographs and MRI of the same patient. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and operative data

Values are presented as number (%), mean±standard deviation, or number. p-value <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

SCPPD, spinal calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; NS, not significant; DCL, decompressive laminectomy; PLF, posterolateral fusion.

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative VRS, ODI, and SF-36 data

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis for each operative procedure in spinal calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition group patients

References

1. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for calcium pyrophosphate deposition: part I: terminology and diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011 70:563–70.

2. Berlemann U, Gries NC, Moore RJ, Fraser RD, Vernon-Roberts B. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition in degenerate lumbar discs. Eur Spine J 1998 7:45–9.

3. Ellman MH, Vazques LT, Brown NL, Mandel N. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition in lumbar disc fibrocartilage. J Rheumatol 1981 8:955–8.

4. Yayama T, Kobayashi S, Sato R, et al. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition in the ligamentum flavum of degenerated lumbar spine: histopathological and immunohistological findings. Clin Rheumatol 2008 27:597–604.

5. Markiewitz AD, Boumphrey FR, Bauer TW, Bell GR. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease as a cause of lumbar canal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996 21:506–11.

6. Fujishiro T, Nabeshima Y, Yasui S, Fujita I, Yoshiya S, Fujii H. Pseudogout attack of the lumbar facet joint: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 27:E396–8.

7. Namazie MR, Fosbender MR. Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition of multiple lumbar facet joints: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2012 20:254–6.

8. Gadgil AA, Eisenstein SM, Darby A, Cassar Pullicino V. Bilateral symptomatic synovial cysts of the lumbar spine caused by calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 27:E428–31.

9. Lee J, Cho KT, Kim EJ. Cauda equina syndrome caused by pseudogout involving the lumbar intervertebral disc. J Korean Med Sci 2012 27:1591–4.

10. DeSouza RM, Uff C, Galloway M, Dorward NL. Spinal epidural hematoma caused by pseudogout: a case report and literature review. Global Spine J 2014 4:105–8.

11. Delamarter RB, Sherman JE, Carr J. Lumbar spinal stenosis secondary to calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition (pseudogout). Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993 289:127–30.

12. Sadique T, Bradley JG, Jackson AM. Central spinal stenosis due to pseudogout: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994 76:672–3.

14. Drouillard PJ, Mrstik LL. Lumbar spinal stenosis associated with hypertrophied ligamentum flavum and calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1988 88:1019–21.

15. Jirarattanaphochai K, Jung S, Sumananont C, Saengnipanthkul S. Reliability of the medical outcomes study short-form survey version 2.0 (Thai version) for the evaluation of low back pain patients. J Med Assoc Thai 2005 88:1355–61.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles in ASJ

-

Role of Coflex as an Adjunct to Decompression for Symptomatic Lumbar Spinal Stenosis2014 April;8(2)