|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 13(2); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Overview of Literature

The anatomical position of the conus medullaris is well-documented in anatomy textbooks; however, the shape of the conus in the canal rarely described. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no study in Korea has not yet assessed the shape of the conus as well as its position in the canal via cadavaric dissection and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Methods

MRI findings of 189 Korean patients aged 2–94 years (93 men and 94 women) were assessed. No subjects from other ethnicities were included. The method proposed by Arai and colleagues was used to assess the termination point and shape of the conus in the canal. The position of the intervertebral disc trisection of the vertebral body closest to the tip of the conus was recorded at the canal level.

Results

The tip of the conus medullaris was positioned from the upper T12 body to the L2–L3 disc, mostly in L1 bodies (52.4%), followed by the L2 bodies (22.5%), the L1–L2 disc, and the L2–L3 disc (1.1%). The shape of the conus was classified as type A in 74 (39.6%), type B in 58 (31%), and type C in 55 patients (29.4%). The conus did not terminate at the L3 body in any patient. In the first decade ones (five children) conus positioned rather lowly from L1 bodies to L2–L3 disc, and no type A conus shape, and mostly type B (80%).

The conus medullaris (CM) terminates in the lower third of L1 (range, T12 to L3). Some authors have reported sex-based differences in the position of the conus and/or thecal sac. However, to our knowledge, no study has yet reported any marked change in conus termination as a function of age in adults. However, few studies have investigated the influence of sex and age on thecal sac termination [1-9]. It is important to consider the possible range of position of the CM in living individuals for several reasons; further, it is crucial to know the location of conus termination while performing diagnostic or therapeutic lumbar puncture and myelography.

Thus, we designed the current study to determine the influence of age and sex on conus termination in a Korean population using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

This study was approved by the institutional review board (MKR: 103). The need for patient consent was waived as the protocols used did not deviate from those used currently. Total 187 non-traumatic Korean patients aged 2–94 years (93 men and 94 women) were included. Their chief clinical complaints included low back pain and sciatica. Of all the patients who underwent lumbar MRI, only those with good, readable MRI results were enrolled; midsagittal images were used.

Lumbar spine MRI was performed at 1.0-T or 1.5-T field strengths (Siemens, Erlarngen, Germany) using a dedicated lumbar spine surface coil and a standard T1 spinecho MRI sequence. The slice thickness was 3 mm. Midsagittal T1- and T2-weighted images (spin time, 100.00 ms; repeated time, 2000.00 ms) were used. All MRIs were retrospectively reviewed as per the study objectives by a consultant orthopedic surgeon and three orthopedic residents to minimize the reading error. We performed the chi-square test for the statistical analyses.

The method proposed by Arai et al. [2] was used to assess the position of the conus in the canal. The position of the intervertebral disc or the trisection of the vertebral body closest to the tip of the CM was recorded as the conus level (Fig. 1). In addition, the shape of the conus in those images by the 1.5T MR machine: Type A was defined as the tip of the conus slant deviated to ventral, type B to central and type C to dorsal (Figs. 2, 3).

The CM was positioned between the upper T12 and L2–L3 discs. In the first decade subjects, the conus terminated between L1 and L2–L3, and no conus was located at T12–L1 and above. In the second through 10th decade subjects, it terminated between T12 and L2. Further, the conus terminated at L1 in 98 patients (52.4%) and at T12 in five (27%). In subjects aged ≤50 years, the conus terminated at one segment lower than that in the other groups above the second decade (Table 1). As per the chi-square test, the level of significance in the five kids for whom the CM terminated at T-12 was 0.05. With respect to the conus shape, type B was the most prevalent (39.6%), followed by type A (31%) and type C (29.4%) (Table 2).

The CM generally terminates at the lower third of L1. However, a wide range of values has been reported in cadaver and MRI studies [1-6]. Moreover, the termination of the CM at L1 has been recognized because of the unparalleled growth of the conus with the bony spinal column during the growth period [4,7-9]. The CM is attached to the coccyx via the film terminale, a thin non-neuronal filament. The conus contains cell bodies and dendrites of the existing L5 to S3 nerve root. Further, the conus occupies a certain percentage of the spinal canal, and its percentile occupancy in the dural sac is also well documented. However, only few studies have examined the positional shape of the conus.

In rare cases, the terminal level of the conus develops clinical symptoms, such as the tethered cord syndrome, when it moves high, up to T11 and above. In contrast, the conus is frequently involved in cases of dorsolumbar spine fracture. Further, only some patients with the same type of fracture resulting from the same level and severity of violence experience nerve damage, whereas few others do not experience any nerve damage because of the conus slant in the canal. When examining patients with acute spinal cord injuries, the examiner employs the Chipault formula (the anatomical relationship between the cord segment and vertebral levels) to predict the injured spinal column level on basis of injured cord level in the accident theater before radiological examination.

Thus, through the present study, we aimed to obtain answers to certain clinical questions. However, our results are limited in their applicability and interpretation for clinical practice with respect to the raised questions. Further, our study is limited by the relatively small sample size and specific study location (i.e., the study was conducted in a limited part of the country, thereby restricting the generalizability of the results).

Compared with those aged ≥20 years, the subjects aged ≤50 years had a more distal distribution of the conus. This finding corroborated with that reported by Arai et al. [2].

The current findings are similar to those reported by Arai et al. [2], based on their study on a Japanese population [2]. Both Arai et al. [2] and we did not observe any highly positioned cases, i.e., above T12, which may elicit tethered cord syndrome. Further, we observed no ethnic, age-, or sex-based differences, even in the elderly subjects.

Theoretically, it is speculated that type C conus experiences the least bruises by the accidentally-retropulsed bone fragment in burst fractures, whereas type A conus is assumed to be most easily bruised, with type B being affected to an intermediate level.

Ventrally-slanted type A conus is generally distal from the lamina. Therefore, it is assumedly less bruised during decompressive laminectomy, whereas a dorsally-slanted conus is more vulnerable to bruises during posterior decompression.

According to Wilson and Prince, the CM does not ascend throughout childhood, and conus termination at L2–L3 or above is considered normal at any age [2]. Our results corroborated with those reported by Arai et al. [2] and Saifuddin et al. [6]. In the current study, the peak distribution of the tip of the conus was at L1, similar to that reported by Wilson and Prince [4]. These findings help explain the differences in the observed severity of neurologic injuries in dorsolumbar burst fractures.

Our study revealed that the conus was located close to the regular distribution, with the peak level at the middle one-third of L1. The most prominent finding was that in the five children aged <10 years, the tip of the conus was located one vertebral segment lower than that in the other age groups. Compared with a study of Arai et al. [2], the conus in our study terminated at the lower one-third of L1.

Differences in the conus slant shape and neurological conditions are believed to be closely related. Some authors have argued that the position of the conus can be altered at postmortem by changing the degree of spine flexion. For this issue the current authors could not plausibly answer, because they did not have the other scan position as a control. MRI was determined as the only method that could help delineate the shape of the conus.

In conclusion, we observed the anatomical height and shape of the CM in 187 Korean patients using MRI. We consider that the differences in the shape of the conus are attributable to anatomical variations. This study provides a description of the level of CM in Korean patients who have been scanned in the supine position.

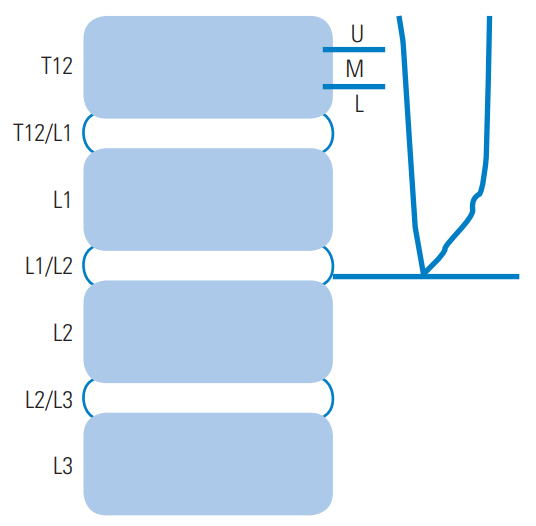

Fig. 1.

The position of the type of conus medullaris in the spinal canal. U, upper vertebral body; M, middle vertebral body; L, lower vertebral body.

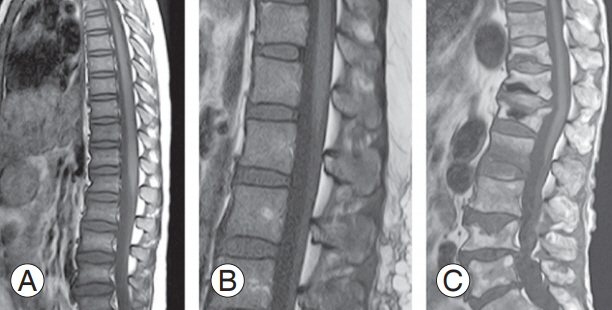

Fig. 2.

Shapes of conus medullaris tip. (A) Type A: n=58 (31%); (B) type B: n=74 (39.6%); (C) type C: n=55 (29.4%)

Fig. 3.

The example of first decade, 40th decade and 80th decade ones, each. (A) A child, aged 7 years, type B; (B) an adult, aged 40 years, type A; (C) an adult, aged 86 years, type C.

Table 1.

Decadal comparison of anatomical height and shape of conus medullaris anatomy in 189 Koreans, based on magnetic resonance findings

Table 2.

Type of cone shape in 189 Koreans, based on magnetic resonance findings

References

1. Spector LR, Madigan L, Rhyne A, Darden B 2nd, Kim D. Cauda equina syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2008 16:471–9.

2. Arai Y, Shitoto K, Takahashi M, Kurosawa H. Magnetic resonance imaging observation of the conus medullaris. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 2001 60:10–2.

3. Reimann AF, Anson BJ. Vertebral level of termination of the spinal cord with report of a case of sacral cord. Anat Rec 1944 88:127–38.

4. Wilson DA, Prince JR. John Caffey award. MR imaging determination of the location of the normal conus medullaris throughout childhood. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989 152:1029–32.

5. Hamanishi C, Horikoshi M, Tanaka S. Distribution of the conus medullaris on the MRI. Cent Jpn J Orthp Traumat 1994 37:695–6.

6. Saifuddin A, Burnett SJ, White J. The variation of position of the conus medullaris in an adult population: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998 23:1452–6.

7. Demiryurek D, Aydingoz U, Aksit MD, Yener N, Geyik PO. MR imaging determination of the normal level of conus medullaris. Clin Imaging 2002 26:375–7.